Gita Class 022, Ch. 2 Verse 69-72

Jun 12, 2021

YouTube: https://youtu.be/0pgql7h-CuE?si=ylGUadEaZ9UDds9f

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

We are coming now to the end of chapter 2. We’ll begin our class as always with some chanting. Please glance at the translation and then repeat after me.

And that’s the last verse of the chapter.

Vasanti, can you turn off the fan? I think. Thank you.

And we’ll get back and introduce our—I think we’ll finish this chapter today. And just to set the context, do you remember that chapter 2 was unique, having a number of different subject matters? Most chapters have one topic. Chapter 2 has several topics.

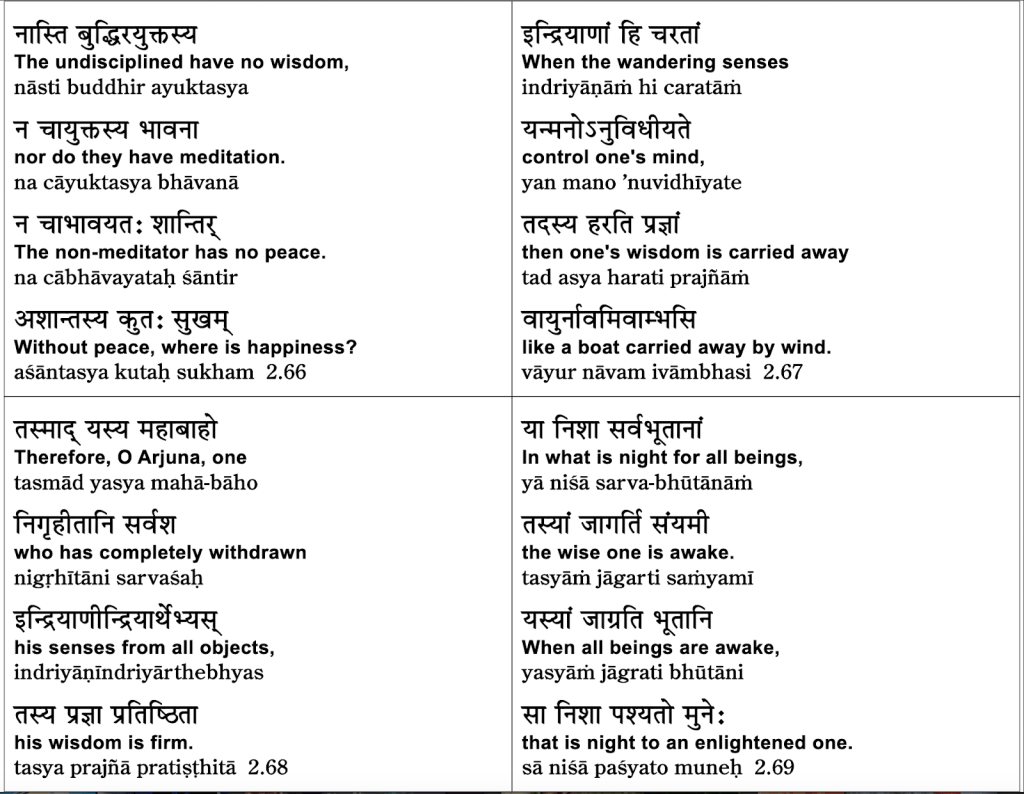

And the last topic, which began with Arjuna’s question back in verse 54—Arjuna asked, what is the nature of the sthita-prajña, one whose wisdom is firm? How does he walk and talk? It was Arjuna’s somewhat misguided question. And then we’ve seen a rather elaborate description about the nature of an enlightened person, sthita-prajña.

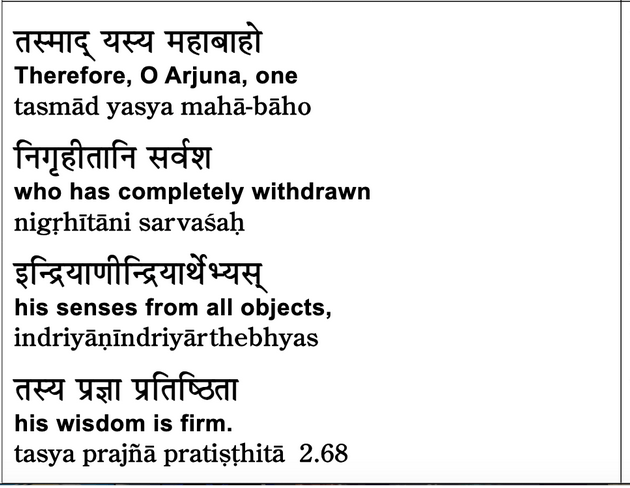

And that description somewhat comes to an end here in verse 68,

which was the last verse we saw in our prior class, where Sri Krishna concludes: tasmāt—therefore—mahābāho, we’ve seen this verse already, O mighty-armed Arjuna, yasya, one for whom (and go down to the third line) indriyāṇi, one whose indriyas, senses—and senses, remember, includes the mind. So not just sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch, but including the mind—one whose senses are nigṛhītāni, restrained, sarvaśaḥ, completely restrained, indriyārthebhyaḥ, restrained from all sense objects. Tasya prajñā pratiṣṭhitā—for that person, that person’s wisdom is firm.

Wisdom is firm for one who has completely restrained the senses and mind from all sense objects.

And please, we discussed a very important point at least twice before: this restraint is not an act of will. This restraint is a matter of discernment. Remember that discussion? When you recognize that no object or person in the world is a reliable source of contentment, peace, and happiness, and when you recognize, conversely, that the true source of contentment, peace, and happiness lies within, this understanding leads to a complete reversal of orientation—where instead of looking for contentment out in the world, you look for contentment within yourself. That is the discernment.

As a result of that discernment, the senses are withdrawn from being dragged about by worldly temptations, as it were. And that concluded, and it sort of concludes, Sri Krishna’s description of the sthita-prajña.

There are several verses at the end of the chapter now which give a different kind of description of that enlightened person—and they’re quite delightful. You’ll see as we continue.

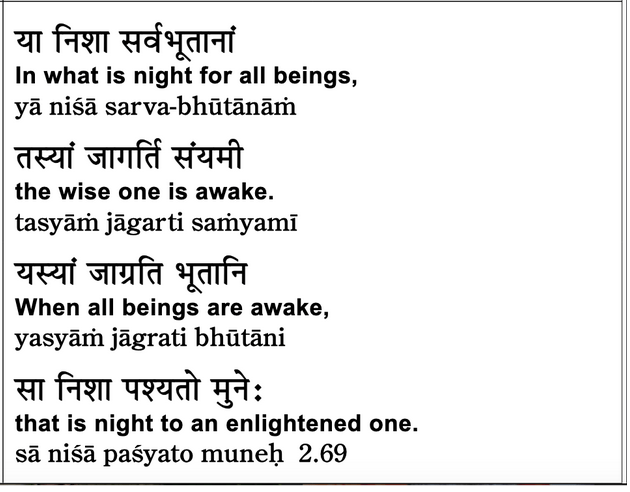

Ya nisa is night, that which is night, sarva-bhutanam For all other beings—for all unenlightened people—so that which is night for all unenlightened people, tasyām, in that condition, jāgarti saṁyamī. Saṁyamī is one who is controlled. And the prior verse talked about one whose senses are completely restrained, referring to that sthita-prajña. So here, in this verse, saṁyamī, one who is self-controlled, refers to that sthita-prajña, one whose wisdom is firm, one who is enlightened.

So that saṁyamī, that enlightened person, jāgarti—is awake—tasyām—in that state.

So that state which is night—and trying to, it’s very poetic, so I’ll try to get a literal translation of the poetry for you—that which is night, that state which is night for all unenlightened beings, in that state an enlightened person is awake. You get the meaning of the words, but what is exactly the meaning? Night here is kind of referring to the dream of ignorance. So it’s a metaphor of dream and waking. And the dream, due to the dream of ignorance, unenlightened people think that the true source of happiness is outside in the world, and they live in that delusion.

Let me see—that’s not… I want to be more in keeping with this poetry. So the contrast—let me finish the verse for you and then try to give it in a more compelling way.

So the first half of the verse says that that which is night for unenlightened beings, in that state enlightened beings are awake. And yasyām, in the third line, yasyām jāgrati bhūtāni—in which state all unenlightened beings are awake—sā niśā paśyataḥ muneḥ—that is night for a wise sage.

What is night for unenlightened beings is waking for the enlightened, and what is waking for the enlightened is night for all the others.

Let me get the sense of it here. Night refers to ignorance. So unenlightened people live their lives in this dream of delusion, constantly looking outside for the true source of happiness which truly lies within. But the enlightened person has awoken from that dream of ignorance. And the enlightened person who is awake to the reality—the enlightened person who is awake to the truth, that ātman, sat-cit-ānanda, your true nature, your divine nature, the inner divinity, as the actual source of happiness—the enlightened person is awake to that reality. But not unenlightened people. They are asleep, as it were, to that reality. Their eyes are closed to that reality. They can’t see that reality.

The commentator gives a cute metaphor. He compares a crow and an owl. And the idea is that a crow can see during the day but can’t see at night. And an owl’s eyes apparently are designed so that they see well at night, but perhaps can’t see well during the day. So the owl is attuned to see through the darkness, whereas the crow is not. And the owl then represents the enlightened person—the one who can see through the ignorance, the one who has shaken off, the one who has pierced through that ignorance, the ignorant conception that some place out there in the world is someone or something that can truly make you happy and continually make you happy.

Of course, there is no such thing. That is the ignorance in which unenlightened people live. Unenlightened people live in that dream of ignorance. The enlightened person has woken up from that dream of ignorance.

So—very poetic.

And the next verse is even more poetic. And you notice that it changes meter. It changes to that longer meter. Most of the verses have eight syllables per quarter. Here we have that very dramatic longer meter for this very beautiful poetic image.

Excuse me, my voice sounds a little funny today.

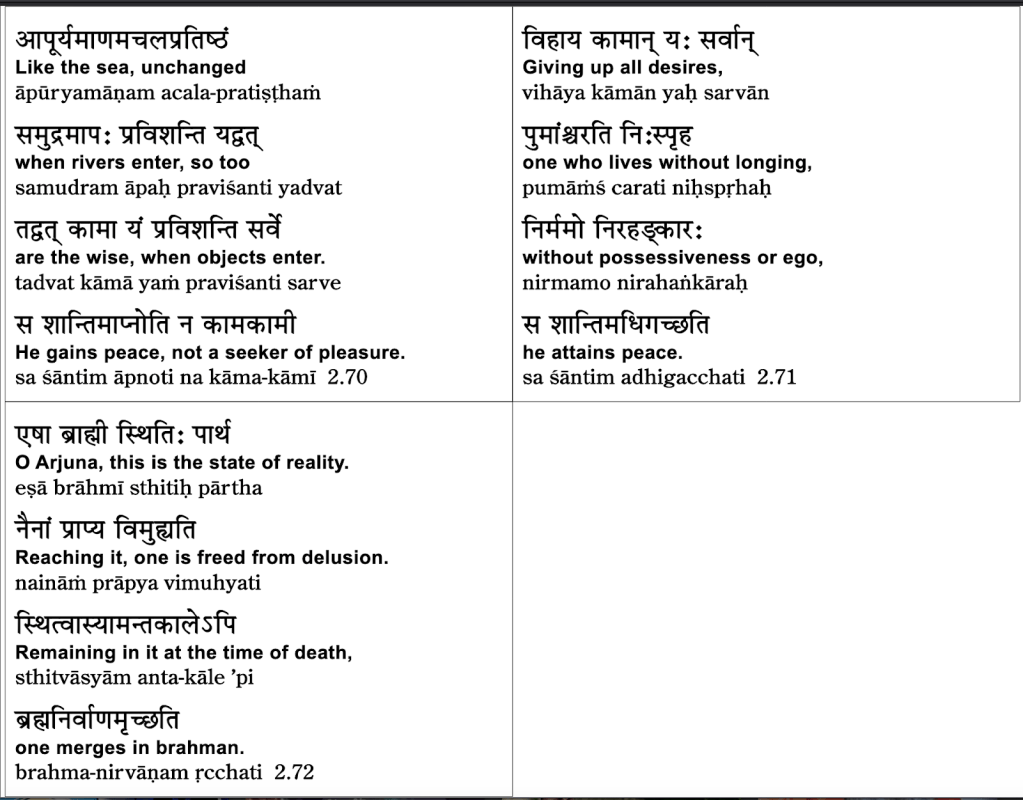

This is a favorite metaphor of mine. And you may have heard me use it before—referring to that inner source of peace and contentment, compared to a vast ocean. Let me give you the sense of the example first, and then we’ll see the words. So you may have heard me— the expression I like to use is: a vast reservoir of peace and contentment lies within you. That vast reservoir is your divine nature. That vast reservoir is your true nature—sat-cit-ānanda-ātma. And that expression that I use so often is based on this very verse. It’s found elsewhere in the scriptures, but this is perhaps the most vivid example of it.

He points out that if you have a vast body of water like an ocean, all the rivers of the world are constantly emptying their waters into that vast body of water—into the ocean, into the sea. But the sea doesn’t rise higher. Also, simultaneously, water is evaporating from the surface of all those vast oceans, and the level of the ocean never goes lower. The vastness of the ocean is such that its level never rises and its level never decreases. This is the infinitude. The vastness of the ocean represents the limitlessness of your own ānanda, of your own innate fullness and completeness.

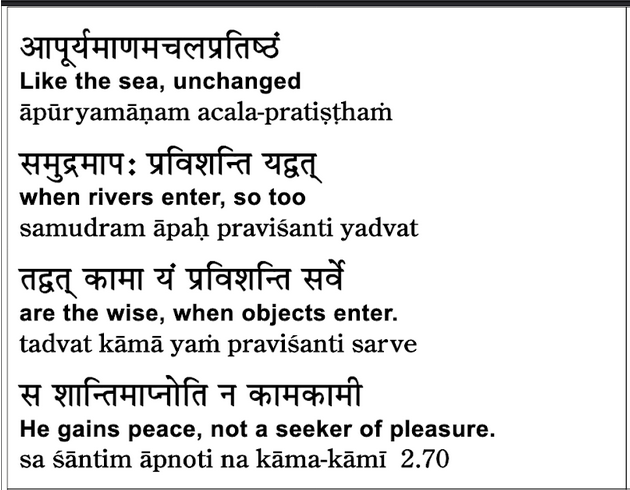

Let’s see the verse, and you’ll see how—excuse me—you’ll see how Sri Krishna describes it.

Starting the second line: yadvat—just as. And then you’ll see the third line: tadvat—in the same way. So these two words set up the metaphor—the dṛṣṭānta. And then in the second half, the dārṣṭānta—that which the metaphor represents.

In the third line: yadvat—just as. And back up a few words and find the word āpaḥ. Samudram āpaḥ. Āpaḥ means waters. So yadvat—just as āpaḥ, waters—what do the waters do? Praviśanti—they enter. The waters of all the rivers of the world praviśanti—they enter into what? Samudram—the sea, the vast ocean.

And what kind of ocean is it? It is, in the first line, an ocean which is constantly being filled—āpūryamāṇam—continually being filled by all those rivers. But acala-pratiṣṭham—its pratiṣṭhā, loosely speaking, its level, is acala—unchanging.

So all the rivers of the world are emptying into the oceans, and in spite of the amazing amount of water entering the oceans, the level of the ocean doesn’t change. Acala-pratiṣṭham, āpūryamāṇam—even though the oceans are constantly being filled, acala-pratiṣṭham—the level remains unchanged.

That’s the metaphor.

Now in the third line: tadvat—in the same way. Kāmāḥ—desires. And here it means objects of desire. Sarve—at the end of the line. Sarve kāmāḥ—all objects of desire, all the things—pardon my loose language—all the goodies of life, all the pleasures of life—that’s a nicer translation. Sarve kāmāḥ—all the pleasures of life—praviśanti yam—enter yam, a person, an enlightened person.

Get the connection. Just as all the rivers of the world enter the ocean, and the level of the ocean remains unchanged—in the same way, yam—for that enlightened person—sarve kāmāḥ, all pleasures enter the enlightened person. But the enlightened person, you have to bring the word down from the first line—acala-pratiṣṭham.

The enlightened person remains unchanged.

When an enlightened person gains some pleasurable experience in the world, in his or her day-to-day life, it says here that the enlightened person remains unchanged.

And this takes some understanding. The limited worldly joys, enjoyed by every person, including an enlightened person—see, the joy of a beautiful morning, the joy of a beautiful morning enjoyed by an enlightened person—doesn’t make the enlightened person more full or complete, because the enlightened person is already infinitely pure, infinitely full, infinitely complete.

Do you remember your math class where you were taught an equation? I have to show you this equation. Oops, oh this one. I wasn’t planning on going to the board, but equations have to be written on a board. And the equation is:

Infinity + 1 = ?

Remember that, right? Infinity plus one is still infinity—it doesn’t change. Infinity plus one million is infinity. Infinity plus any number remains infinite. You can’t go beyond infinity. Infinity is that number which cannot be transcended. And that infinity represents the fullness or completeness of an enlightened person.

Similarly, I won’t go back to the board, but if I took infinity minus one, it’s still infinite. Infinity minus one million is still infinite. So here, now you’re getting it.

So when an enlightened person enjoys a worldly pleasure, the worldly pleasure cannot possibly add to the innate fullness and completeness of the enlightened person. And when an enlightened person suffers some problem—if an enlightened person has an investment, and the investment is a disaster, and the enlightened person loses millions of dollars—the enlightened person loses nothing. And the metaphor is the ocean—we’ll call it the ocean of ānanda—that inner reservoir of peace and contentment. Because of its vastness, you can’t add anything to it, nor can you detract from it. Which means an enlightened person cannot, through any effort, become more enlightened, become more peaceful, more complete. Already fully complete, already perfect, at perfect peace.

In the same way, any series of difficulties that the enlightened person might meet cannot detract in any way from that inner fullness and completeness.

I’ve often used that metaphor in describing how generally, when we help people, you kind of give of yourself. And you give and you give and you give. And many people experience running dry over a period of time—running out of love and compassion. It’s like for a caregiver, someone who is constantly caring for others, there’s such a thing as burnout, because there’s only a finite amount of physical and emotional energy that caregiver has.

Suppose it were an enlightened caregiver. Now, bear in mind an enlightened caregiver still has the same physical limitations and still has some emotional, normal human emotional limitations, because these are limitations of the body and mind. And those limitations will always be a fact. But the enlightened person is one who has discovered within himself or herself this vast reservoir of peace and contentment. So as a caregiver, that enlightened person would be able to tap in, so to speak, to that infinite inner reservoir.

And that’s what Sri Krishna is referring to here. So all the waters of all the rivers can flood into the ocean—the ocean doesn’t rise. And all the pleasures in the world can be enjoyed by the enlightened person—any enlightened person—will not be enhanced in any way by those pleasures.

And even Sri Krishna only gives this half of the idea. The converse is equally true. And that is: the waters are evaporating from all the seas in the world, and their level never falls. In the same way, the enlightened person can undergo any number of difficulties, problems, and disasters, and the enlightened person will not be diminished. That inner reservoir of peace and contentment—sat-cit-ānanda, your true nature—will not be diminished.

That which is your true nature can’t change. Ātma, consciousness properly understood, is unchanging. Being unchanging, you can’t add to it, and it can’t be diminished.

And then Sri Krishna concludes: saḥ—that person, that person who in a prior line, the person who doesn’t change when enjoying all the pleasures of the world—in a final line, saḥ, that person, śāntim āpnoti. That person āpnoti, gains śānti, peace.

That person gains peace. Na kāma-kāmī—not one who is seeking worldly pleasures. Kāma-kāmī—worldly-pleasure seeker. Kami—one who seeks. So by seeking worldly pleasures, kāma-kāmī, one who seeks worldly pleasures, will that seeking ever be fulfilled?

You’ve had this discussion before. When will worldly seeking culminate in a state of perfect satiation? Temporary satiation, absolutely. You sit down and eat a wonderful meal—you’re temporarily satiated. But then you’re hungry several hours later. Or you go to the local mall and you buy a lot of goodies at the mall—you are temporarily satiated. But that satiation goes away, and you go shopping again the next day.

Whatever you accomplish in life will bring you temporary joy and contentment—temporary satiation—never permanent, complete satiation. So that’s what he says here. Na kāma-kāmī—the one who seeks śānti, peace, through worldly activities, will never achieve perfect peace, uninterrupted contentment. That satiation here is called śānti.

Who does achieve this śānti? The one who turns within for the sake of contentment and peace.

Okay, continuing. Nice verse—what very nice poetry.

Next:

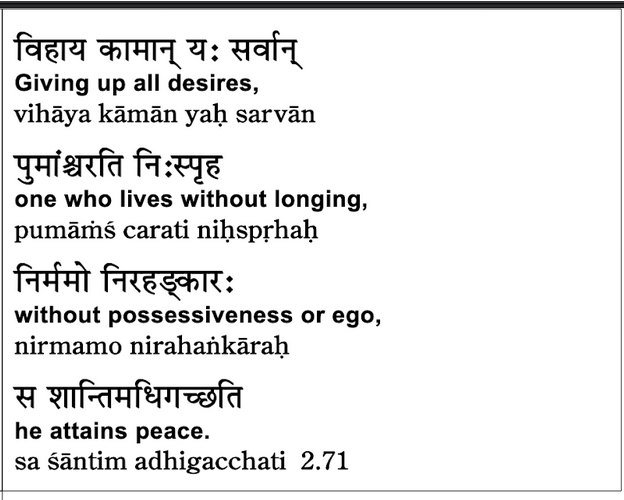

Yaḥ—in the first line, yaḥ, one who. Vihāya—having given up. Kāmān—objects of desire. Sarvān—all of them. So yaḥ—that enlightened person, one who vihāya, having given up sarvān kāmān, all objects of desires.

And remember, as we said before, this giving up is not an act of will. When you— I think I’ve given this metaphor previously—when a child gives up a toy, a child that had a stuffed animal toy. You may have had such a toy as a child. Suppose you had a stuffed animal as a toy, and suppose it was your favorite toy, you were so fond of it. You probably don’t have that toy today—probably not.

And does it mean at some point in time, you decided to give up that toy? You never decided to give it up. Giving up that toy was not a willful act. What we say is: you outgrew that toy.

And I believe I gave this metaphor before with the bicycle or car example. You outgrew the toy. You discerned—it’s a matter of discernment. Prior to discernment, you thought that toy was truly a source of happiness. After you became a little bit more mature, you could discern the truth that that toy is not an actual source of happiness. With that discernment, you outgrew the toy.

So here, the gerund used here is vihāya—having given up. But it’s more in the sense of having outgrown. You don’t give up desires, you outgrow desires. Can I say that again?

You don’t give up desires. Remember our example of tea—you can give up drinking tea. You can’t give up the desire to drink tea. You don’t give up desires, but you can outgrow desires. How do you outgrow desires? By discerning that the things you desired are not truly the source of happiness and contentment.

That is the discernment. Through that discernment, you outgrow desires.

Okay. Vihāya kāmān yaḥ sarvān.

So that yaḥ—one who, that enlightened person, who outgrows all desires. That in the second line, pumān—that person. What about that person? Carati—that person goes on living. That person lives niḥspṛhaḥ—free from spṛha, free from longing, free from attachment.

Remember our definition of attachment: emotional dependence. You can have many things in life, but if you are emotionally dependent on having them—form of bondage.

Allow me to give a powerful example. Many of you have raised children. So you love your children, absolutely. But for most parents, there’s also attachment to the children, which means emotional dependence on the children. And that emotional dependence is a kind of bondage. That means when the children suffer, you suffer. That’s bondage. You should be delighting in having children. But when your children suffer, you suffer. That is emotional dependence. That is attachment.

But here the enlightened person—pumān—that person, carati, goes on living niḥspṛhaḥ—without this attachment, without this longing.That enlightened person is nir-mama. Mama is the Sanskrit pronoun “my.” Nir-mama is one who is free from “my-ness.” Imagine having children without thinking of them as my children.

My guru, Pujya Swami Dayananda, would speak to this frequently, because he would often be teaching parents of children, and he observed again and again how attached so many of these parents were. And he would be rather bold by saying: “Your children are not your possessions. Your children are not your possessions. They are independent beings with their own lives, their own karma. They are completely independent.”

And Pujya Swamiji was fond of using a word to help transform one’s relationship. Instead of having children, you are the caretaker of your children. Instead of having a home, instead of owning a home, you are the caretaker of the home. Instead of owning a car, you are the caretaker of that car. Instead of having a possession, you are the caretaker of that possession.

And using that word caretaker, Pujya Swamiji was trying to shift everyone’s orientation away from that possessiveness and emotional dependence. If you are just the caretaker, you don’t have that sense of possession. Mama here means that sense of possession. So nir-mama—the person is free from possessiveness.Your children are not you procession and nor is your home. Many of you have a mortgage so it is owned by your bank, but even when your mortgage is paid off, what does it mean to say my home that processiveness is a problem and if it is my home and it burns down you have a problem, if it was a caretaker for your home and it burns down then you wont suffer in the same way. nir-mama—the person is free from possessivenes Nir-ahaṅkāra—and free from pride. I guess pride goes along with possession: my children, my profession, my car. So that pride that comes along with your possessions.So that enlightened person who becomes freed, that enlightened person who—paraphrase the first three lines: the enlightened person who outgrows all desires, goes on living free from attachment, free from possessiveness, free from pride of ownership.

Saḥ—that person. Śāntim adhigacchati—that person adhigacchati, gains śānti, gains peace.

It’s important here to address a common argument. Referring to the first line: “one who gives up all desires.” It’s a very common argument, raised—and a good argument is: wait a minute, doesn’t desire drive us to improve ourselves? Desire drives us to improve the world. Desire drives achievement.

Does it? What do you really desire?

And again, I’d like to go back to my teacher’s words here. He gave a unique analysis of desire:

Desire is a label. Desire is a label given to an inner sense of incompleteness.

I’ll say that again—it’s an unusual statement.

I’ve never heard anyone else describe desire in this way.

He said, desire is an expression of an inner sense of incompleteness. When you feel somehow inadequate or incomplete, therefore you desire. And you desire great many things in life because all those things in life can perhaps fulfill that lack that you feel within yourself, that inner sense of completeness.

So try this. If a scientist is working to improve mankind—very lofty—a scientist who is working to improve mankind, what would be the motivation of that scientist? Well, and some of you may know that Vesanti, my assistant, is a scientist. She works with other scientists. She works in a laboratory in a major university. And she sees a problem all the time. And that is, scientists are generally not driven to improve the state of mankind. Scientists are driven for purely personal reasons. They want to advance in the academic world. And how do you advance in the academic world? You move up from being an assistant professor to a full professor and finally a tenured professor. You know, so you get these degrees of advancement. You publish many papers, you become well-known. Everyone in your scientific community looks highly upon you. Turns out that the majority of scientists are not driven to improve the state of mankind. They’re driven by that inner sense of incompleteness, just like anyone. This is the fundamental driving factor for all people.

We went. We had long discussions before of Raga Dwesha. Raga—we chase after things we think will make us happy and content. Dwesha—we run away from things that will deny us happiness and contentment. Our ordinary lives are driven by Raga Dwesha. And Raga Dwesha is an expression of desire.

So a scientist who’s driven by such desires is not necessarily focused on improving the state of the world. Fortunately, fortunately, a great number of scientists are driven by a genuine thirst for knowledge. That’s wonderful. And a few scientists are genuinely driven by wanting to improve the state of mankind. They’re driven by Dharma to help others. It’s Dharma. In fact, those scientists are karma yogis. Those scientists who are driven not to fulfill personal agendas and not even driven by this thirst for knowledge, but those few scientists who are driven by Dharma, by a genuine need to improve the status of mankind—in my view, those scientists are truly karma yogis.

So the point here is: desire is not necessary for achievement. Don’t think someone who is desire-less doesn’t get out of bed in the morning. The one who has outgrown desires does what needs to be done because it’s Dharma. Ordinary people are driven by Raga Duesha, and an enlightened person is naturally motivated to follow Dharma. It’s so simple. Ordinary people driven by Raga Duesha, an enlightened person freed from Raga Duesha is motivated to follow Dharma.

Enough said. We’ve had a lengthy discussion of that quite a while ago. And that brings us to the final verse of chapter two.

O Sri Krishna says:

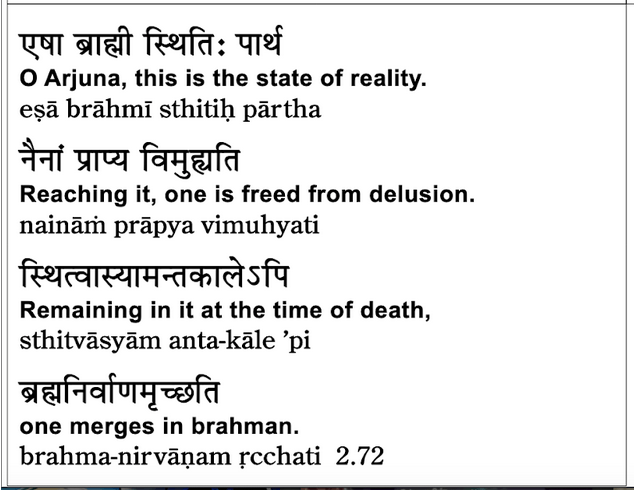

Parta, O Arjuna, son of Pratu. O Arjuna, Aisha, this stitihi, this state or condition is Brahmi, is reality. Brahmi stitihi is a state of reality. A state of absolute reality, a state of enlightenment.”

So that word stitihi is related to stita pragna—one whose pragna, wisdom, is stita (firm). So that firmness, that stitihi, that firmness of wisdom, is Brahmin stitihi. It is being established in reality. This is the state of enlightenment.

Notice a state of enlightenment is described here not as a state of experience. Sometimes people have this funny notion that enlightenment is a state of being immersed in bliss. Being immersed in bliss is wonderful, and through meditation you can be immersed in bliss. In fact, if you’re like me and you like ice cream, eating ice cream kind of immerses you in bliss—you don’t need meditation!. Enlightenment is not immersion in a temporary state of bliss. What is it? That’s what the whole second last part of this chapter is about. It is stitihi. It is being established in wisdom. Stita pragna—that’s what Sri Krishna has been teaching here, verse after verse after verse. Enlightenment is not a temporary state of bliss. Enlightenment is being permanently established in wisdom.

Esha brahmi stitihi.

Enaam propya. Anam propya—having achieved propya, having gained. Anam, you have to break up the words—nha anam propya. Enam propya—having achieved this stiti, this brahmi stiti, having achieved the state of enlightenment—nha vimkhya ti.

One is never again deluded. One is never again subject to delusion. Once you outgrow that toy, you never again look upon it as a true source of contentment. When you were a child, you loved that toy. Once you outgrow it, you may still have fondness for the toy, but you will never again consider that toy to be an actual source of happiness and contentment.

So Enam propya—having gained this state of being permanently established in wisdom—nha vimkhya ti. One is never subject again to delusion, to confusion, to ignorance.

In the third line, stitwa, a siam, antakalea pi. Stitwa—having, literally “having state,” you translate it as “abiding.” Stitwa—remaining in that condition, abiding in that condition.

Notice—you cannot abide in a state of bliss. You can enjoy in meditation or eating ice cream. You can enjoy bliss for a period of time. It will eventually go away. Here, stitwa—permanently abiding, not in a state of bliss, permanently abiding in this wisdom, in this understanding. The understanding that nothing in the world is necessary for your fullness and completeness, which is an innate truth and already existent fact of who you are.

Stitwa—remaining, abiding, asyam—in this state, in this condition. Antakalea, pi. Api—even. Antakalea—even at the time of your death. Anta—end, and kala—time. The kala, the time of your anta, your end, your death.

So, abiding in this wisdom at the time of death, bramha nirvanam rachati. Rachati—one gains, one achieves bramha nirvanam.

What a profound term! Nirvana, as you’ve probably heard it described, is a condition of dissolution, merging. It’s often explained by when a candle flame gets extinguished. They used that candle flame being extinguished to describe nirvana.

There’s a common confusion here, though. When the candle flame is extinguished—in ancient times—this is a sign that in modern times we know that the flame just ceases to exist. But that metaphor of the candle flame being extinguished is based on a pre-scientific understanding.

In order to understand that candle flame metaphor, you have to understand how they used that candle flame metaphor. And in ancient times, they thought that when that flame is extinguished at the candle, that individual flame merges into the universal principle called Agni.

Agni—fire—was considered an all-pervasive universal principle. So that little flame merged into the all-pervasive principle called Agni. The little flame merges into the whole.

So when nirvana is explained as a candle flame being blown out, it’s not describing the end of the existence of the candle flame. But rather, it’s describing how that individual flame merges into the whole.

And here that expression is found: Brahma-nirvanam-rachati. Nirvana—rachati—one gains. Nirvana—dissolution. Brahma—brahma-nirvana—into Brahma. Merging into Brahma. Nirvana—becoming utterly non-separate from Brahma. Nirvana—not a state of non-existence, but rather the part merges into the whole. The individual person loses his or her individuality and becomes utterly non-separate from Brahma—absolute reality.

That brings us to the end of chapter two.

And a nice way to conclude our study of chapter two would be to return to my English translation. We’ve seen this a couple of times already. This English translation, you remember, I composed it following the meter of the original Sanskrit. And we will recite it.

So we will—because it’s composed in the meter of the original Sanskrit—we can recite this translation the same way as we recite the Sanskrit verses. It’s also somewhat condensed, so it’s not very long. And it’s a really wonderful way to get the summary of the chapter, to get the so-called bird’s-eye view and overview of the chapter.

And so we’ll conclude our study today, reciting this. I think maybe the first two verses you can listen and repeat. And then you’ll be able to follow.

So with the starting with the third verse, we’ll recite together.

First two verses—listen and repeat, just to remember how we do this.

Sanjaya said

Then lord krishna did thus address arjuna sunk in deep despair

with eyes downcast and full of tears overcome by his tenderness

The blessed lord said

o Arjuna how can you be, disheartened at this crucial time

you’re impious and shameful mood, will bring you down in great disgrace

yield not to this unmanliness for befits you not at all cast off this mean faint-heartedness

arise and fight o arjuna

Arjuna said:

“Oh Krishna, how can I oppose Bhishma and Drona in this war? How can I pierce with arrow sharp those worthy of my reverence? Rather than slaying such great men, better to live a life of bounds, since by killing them I would gain their wealth and treasures stained with blood.

By weakness I am overcome. As to dharma, I am confused. Tell me for certain what is best. I am your student. Teach me please.”

Sanjaya said:

“After saying, ‘I shall not fight,’ silently, Arjuna did sit. Then Lord Krishna began to speak, with a slight smile upon his lips.

The Blessed Lord said:

You mourn those who need not be mourned, yet you speak words of wisdom. To the truly wise, mourn not for those who are dead and those yet to die. Never have I existed not, nor have you, nor these kings of men. Nor shall we ever cease to be in the future and later lives.

The one who in this body dwells, through childhood, youth, and in old age, will then another body gain. In this the wise are not confused. These bodies destined to expire, all possess an eternal soul, indestructible beyond thought.

Therefore, go fight, O Arjuna. Neither born nor subject to death, the soul will never cease to be—eternal and immutable, living on when the body dies. Just as one casts away worn clothes, dressing again in new attire, so too when old bodies expire, a soul acquires others new.

Not by weapons can it be pierced, nor by fire can it be burned, not by waters can it be wet, nor by winds can it withered be. Unmanifest, beyond all thought, unchanging—thus our soul’s described. Therefore knowing this to be so…”

You have no reason now to mourn. Death is certain for all those born, and birth is certain for all who die, since this is inevitable. You have no reason now to mourn.

Also, with your dharma in view, you should remain unwavering, because for warriors nothing is worthier than a righteous war. But if you now refuse to fight in this battle, most virtuous, you will forfeit dharma and fame by committing this grievous sin.

Great warriors will despise your name, thinking you yielded due to fear. Your enemies with vicious words will degrade you—a dreadful shame. If you die, heaven you will gain. If you win, the kingdom is yours. Therefore stand up, O Harjuna, and be resolved to fight the war.

Sri Krishna introduces a topic of karma yoga. Thus far of wisdom I have spoke; of karma yoga listen now, practicing which you shall be freed from the bondage of all your deeds.

Those who seek but pleasure and power attach to Vedic rituals, obsessed with heavenly rewards—their hearts will never be at peace. Like a pond in a mighty flood, water surrounding everywhere, such is the worth of Vedic rites for one who knows the highest truth.

Actions alone you can control, but their results you cannot choose. Be not the author of the fruits, yet to an action be not drawn. Give up attachment to results. Act instead with this attitude: treat success and failure alike. Yoga is equanimity.

Lowly are those who think themselves to be the authors of the fruits. Arjuna, you should seek support in karma yoga’s principles. By this yoga the wise renounce attachment to their works’ results. From the bondage of rebirth they reach the state beyond all grief.

Bringing us to the final topic: stitapragnya—the one whose wisdom is firm, introduced, as I said, by Arjuna’s question.

Arjuna said: O Krishna, please describe to me the nature of enlightened ones. How do the steady-minded speak? How do they sit and move about?

The Blessed Lord said: O Arjuna, when they forsake all cravings born of their own minds, content in themselves with the self, such are they whose wisdom is firm.

With minds untroubled by distress, free from thirst for the world’s delights, having no cravings, fear or rage, such are they whose wisdom is firm. Rejoicing not in pleasant times, nor detesting adversity, free from every attachment here, such are they whose wisdom is firm.

As a tortoise withdraws its limbs, all their senses are drawn away from the objects that they perceive—such are they whose wisdom is firm. Even for those of wisdom vast, who strive to practice self-control, their minds can be carried away by the senses, so turbulent.

Dwelling on objects in the world, to them attachment does arise. From attachment, desire stems forth. From desiring does anger spring. From such anger delusion comes. In delusion values are lost. Then reasoning gets overwhelmed, and finally the person is lost.

But those remaining self-controlled, even when senses clamor strong, free from cravings, despising not, they attain great tranquility. Just as wind carries boats astray, senses can lead wisdom away. Therefore those whose wisdom is firm restrain their senses constantly.

With this verse, the condensed English translation comes to an end. You can find this text on our website—you’ll find a link in the description below. You’ll also find all the English verses recited in a separate video on my YouTube channel; take a look at that if you’re interested.

So nice to get this overview of chapter 2. In our next class we’ll begin chapter 3, Karma Yoga. We’ll conclude with the prayer.

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ असतो मा सद्गमय ।

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय ।

मृत्योर्मा अमृतं गमय ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Asato Maa Sad-Gamaya |

Tamaso Maa Jyotir-Gamaya |

Mrtyor-Maa Amrtam Gamaya |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om, (O Lord) From (the Phenomenal World of) Unreality, make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the Reality (of Eternal Self),

6: From the Darkness (of Ignorance), make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the Light (of Spiritual Knowledge),

7: From (the World of) Mortality (of Material Attachment), make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the World of Immortality (of Self-Realization),

8: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om, Tat Sat. Thank you.