Gita Class 021, Ch. 2 Verse 64-68

May 29, 2021

Youtube: https://youtu.be/h4xyX_yei0I?si=lp0Ua4EkhG3rh-hl

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

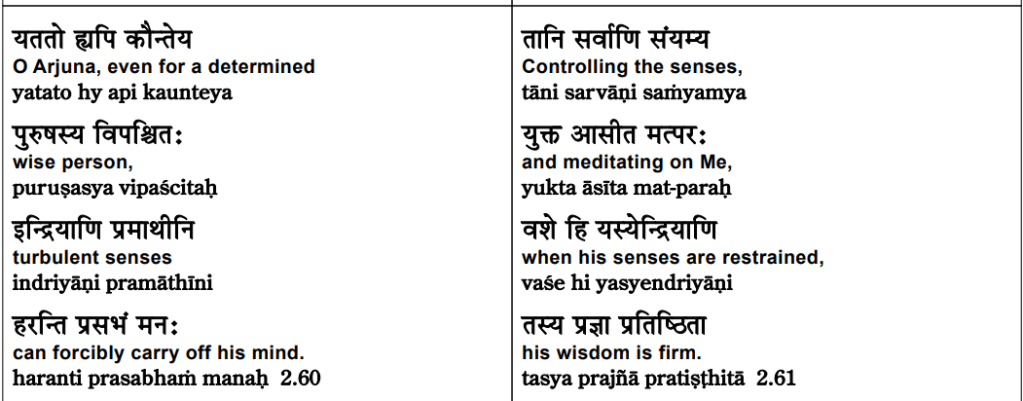

Good. Welcome to the webcast of my weekly Bhagavad Gita class. We continue today in chapter 2. We begin always with some brief recitation. We’ll start today with verse 60. Please glance at the meaning and then recite after me.

Very good.

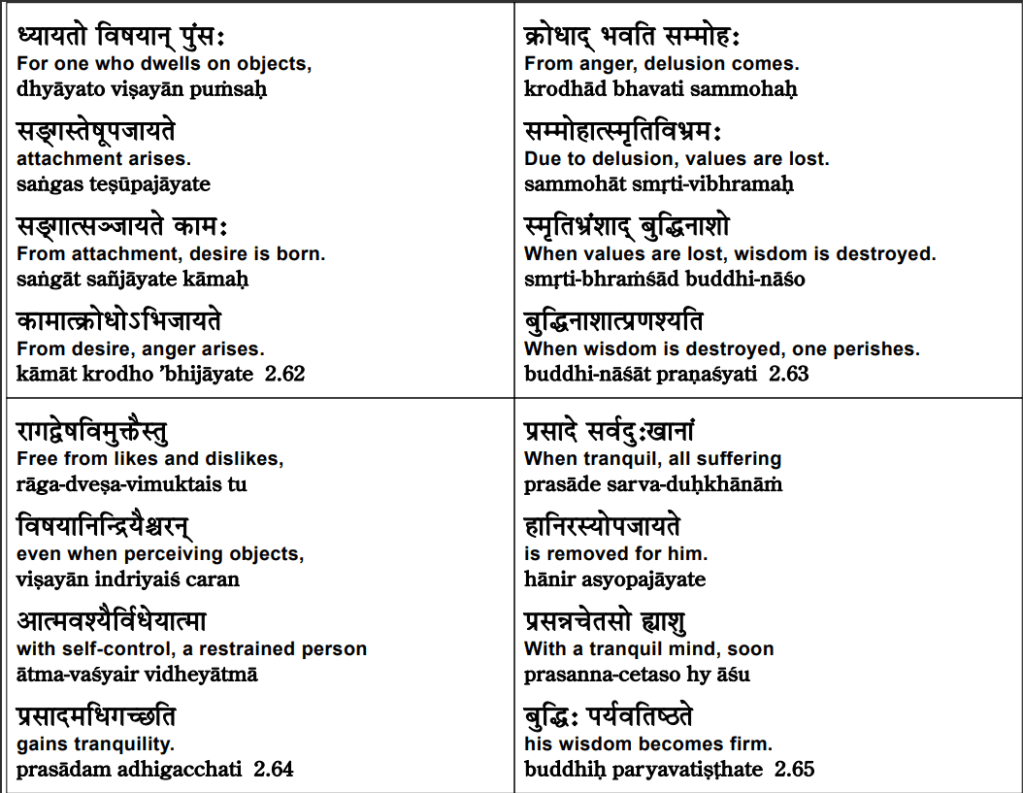

In our last class we saw that we ended with this pair of verses, 62 and 63, which wonderfully give an account of the slippery slope by which we get carried away by our senses and end up committing terrible—possibly end up committing terrible acts of Adharma.

Let’s just review those two verses briefly and before we continue. So each of the four quarters of the next two verses—each line—gives one of the eight steps.

The first one: Dhyayata Vesayan Pumsaha. For a person who goes on Dhyayata, for one who is dwelling upon Vesayan—objects of the senses. When you go on dwelling upon an object, Sangha—I won’t translate, we saw that verse yesterday.

So the second line: Sangha—attachment. Upajayata—arises towards the objects. Remember our definition of attachment: emotional dependence. When you feel like your well-being depends on getting that object or avoiding other objects.

Then, in the third line: Sangha, Sangha. It says: Kamah. Kamah—desire arises from attachment. When you see an object as essential for your well-being, Kamah—you want it.

Kamaat, Kroda, Abhijayata. And Kroda arises from Kamah. Kroda—anger—arises because when you have a desire, there’s usually one or more obstacles preventing you from fulfilling your desires.

Then Kroda, from Kroda, what arises is Samoha—delusion. That Kroda begins to distort your thinking, your reasoning. We call that Samoha—delusion.

Samoha—and from that delusion what arises is Smriti Vibramaha, which we translated as a loss of your values. The values for following Dharma, that you’ve assimilated fully—those values get overwhelmed, those values get lost.

Smriti Vibramaha, and when your values are overwhelmed, Buddha Nāshaha—your intellect gets literally destroyed. “Corrupted” is a better idea here.

Buddha Nāshaha, pranashyati. And when your intellect gets corrupted, pranashyati—your life gets destroyed because you end up committing acts of Adharma and suffering the consequences for those.

Now before class I took a moment and wrote all of these up on the board, just so you can see in one view the eight steps, so that we can discuss now: where can we break this chain?

It’s called… here we go. Let me explain first. It’s called a slippery slope because once you get started you can’t stop.

As a child growing up in Wisconsin—a very cold place—we would ride sleds down in winter. We’d ride a sled down a slope covered in snow. Obviously, once that sled starts going, there’s no way to stop until you reach the bottom of that slope. So this is the idea of slippery slope—a moral or ethical slippery slope. Once you get started in that downward direction, you’re swept along.

And our question now is: where can… how can we avoid this slippery slope?

And now we pick up the thread where we left off in the last class. I said that once—start with number two—once you have Sangha, attachment, Kama—desire—is inevitable, unavoidable. And once you have Kama, Kroda—anger—is unavoidable because there are always obstacles to your fulfillment of those desires.

And once you have Kroda, this Samoha is inevitable because Kroda will always distort our thinking. Once you have that Samoha, Smriti Vibramaha—eventually your values are going to get overwhelmed. And then Buddhinashaha—then the corruption of your thinking and reasoning is inevitable. And pranashyati.

There’s a sense of inevitability. Once you gain that Sangha, you get swept along by that attachment from one to another, and there seems to be no way to break out of it.

How to break out? Well, one approach is to avoid step one, which is never to observe anything desirable. Well, unless you’re ready to live in a cave, that’s impossible. As long as you’re living a conventional life, you’re going to be exposed to all kinds of objects of desire. So avoiding step one is not an option.

The key then to avoiding the slippery slope is number two: attachment. So you can see objects which are desirable without getting attached to them.

If you remember in our last class, I gave that lengthy example using a Lexuscar—any fancy car. And the example I gave is Dhyata—step one, when you see that Lexus commercial again and again and again, what can happen is Sangha—attachment arises.

And Sangha, attachment, is that emotional dependence, that sense that your well-being depends on you having a Lexus. Well, that’s not true. You can be perfectly fine without a Lexus. I don’t have a Lexus. I don’t have any problems. Most people don’t have a Lexus and they’re perfectly fine.

So what happens here is some wrong thinking, wherein you see that Lexus commercial again and again, and the commercial advertising is successful in implanting a desire in your mind. It’s like being programmed with this advertising propaganda. They were successful. That you can avoid.

And not just with regard to a Lexus, but with regard to everything in life. When you really—and now we have to go back to our earlier discussion about karma yoga. We said one of the basic principles of karma yoga is the recognition that whatever you can accomplish in this life with your efforts will never, ever bring you perfect peace and lasting contentment.

Let me say that again because this is one of the foundational principles of the entire Bhagavad-gita, of Vedanta itself, Advaita Vedanta. It’s the importance of the recognition that your finite, limited efforts in life to get what you want and avoid what you don’t want—those limited efforts will never be successful in bringing you perfect peace and uninterrupted contentment.

This recognition really is the beginning of a spiritual journey. You recognize the limitation of what you can accomplish in the world, and you start to redirect your attention towards a process of spiritual growth. In that process, you recognize that nothing in the world can bring you perfect peace and contentment.

It’s true, right? Nothing. Nothing and no one—no person in the world—can bring you perfect peace and contentment. That perfect peace and contentment is only available within you. It’s your true nature, that inner divinity. By turning your attention within, you can indeed gain that perfect peace and contentment.

This recognition is a complete conversion of the way you think. Excuse me. And with this conversion of thinking, attachment goes away, right?

No matter how many times you see that Lexus commercial, you will know without a shadow of a doubt—you’ll know that Lexus, oh, I’m still looking at that. Sorry. I think you’ve looked at that list long enough, I should have put this back on me.

So you will know through this conversion of thinking that the Lexus can never bring you perfect peace and contentment. Nothing in the world can bring you perfect peace and contentment.

With this recognition, Sangha—attachment—goes away. And when you don’t have Sangha, even when you see the Lexus commercial, you’re not carried away.

So even when you have that first step—Dhyayata, Vesayan, dwelling on objects—you will not be swept into step two, attachment, because of this discernment. Discernment of the limitations of whatever you can gain through your worldly efforts.

And that discernment, which removes attachment, is what’s discussed now in the coming verses.

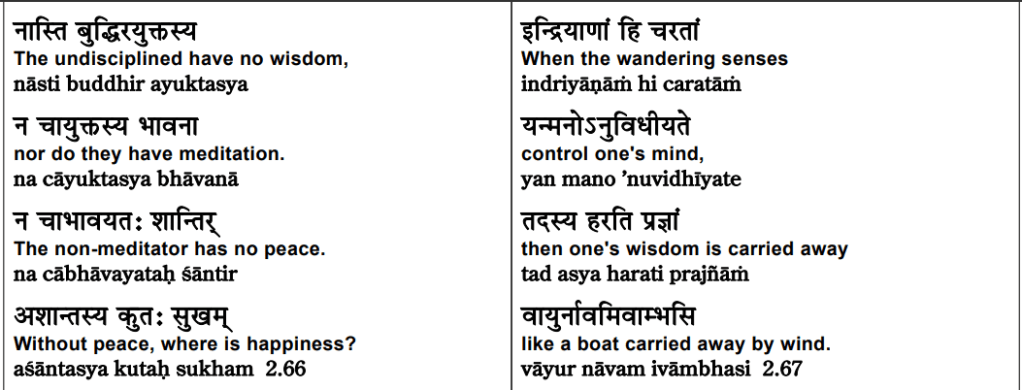

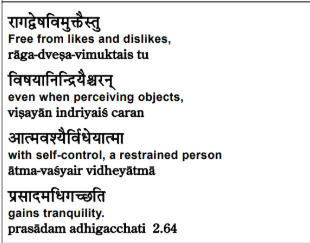

Raghadwesha Vyupthaihi.

Tu, Tu—but. But Raghadwesha Vyupthaihi. Vyupthaihi—by becoming free. By becoming free of what? Ragha and Dvesha.

Remember, Ragha is a compulsion to get what you want. Dvesha is a compulsion to run away from what you don’t want. And those are both examples of Sangha—attachment. Raghad and Dvesha are forms of attachment. Attachment to get what you want, attachment to avoid what you don’t want.

But, tu—but. Raghadwesha Vyupthaihi. One, due to being freed from Raghad Dvesha, being freed from Sangha, being freed from attachment.

Vesayan Indriaihi Chharan. Chharan—even when. Even when Vesayan. Even when, even one. Chharan Indriaihi. Even when—your senses. Indriya—senses.

Remember, senses are not just sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch, but the sixth sense: mind, Antakarana. So senses and mind. So when you see “senses,” almost always it means senses and mind. When your senses and mind Chharan—even when they are engaged, even when they encounter Vesayan, objects, sense objects, like the Lexus commercials, etc.—so even when your mind and senses come in contact with all these desirable objects in the world, Raghadwesha Vyupthaihi—because you are free from Raghad Dvesha.

Atma Vashyaihi. Because Vasha is controlled. Atma Vashya—control of Atma. Atma is not controlled—be careful here. Atma doesn’t mean consciousness in this context. Atma does not mean Sat Chit Ananda Atma. Atma can often mean self in a general sense, and here Atma means mind. In fact, Atma comes twice in this line, and both times it means mind. In the Bhagavad Gita, Atma is used in several senses. In one place it even means body. Atma means self, and sometimes self can refer to your body. Frequently, Atma can refer to mind.

So here: Atma Vashyaihi—by the control of one’s mind. Videya Atma—one whose Atma is Videya, well controlled. And here Atma again has to mean mind.

One whose mind is self-controlled—for that person, one whose mind is self-controlled because they are freed from Raghad Dvesha. Even when the mind and senses come in contact with different things—for such a person, Prasadham, Adi-gachati—that self-controlled, restrained person, Adi-gachati—gains Prasadham.

By the way, Prasadham doesn’t only mean what you get in a temple after Puja is over. Prasadham also has many meanings, like when water is clear, that clear water is called Prasadham. Here Prasadham means tranquility.

Be careful—different, like Atma has different meanings in different contexts, Prasadham has different meanings in different contexts. Here it means tranquility.

Please note that you gain—this person who is self-controlled and restrained. Controlling one’s senses, the sense of restraint. The sense of restraint is not a matter of willpower. Be very clear about this.

We’ll come back to this point in several verses. It’s not a matter of willpower. When you see the Lexus commercial again and again, and if you—I’m being silly—imagine someone who gets an impulse to get up and go to drive to find an automobile… what do they call it, the dealer? An auto dealer, automobile dealer, who deals in these Lexus cars. And you’ll get that impulse to go to the dealer and buy a car.

I’m not talking—these verses do not describe that kind of self-restraint or self-control. It is discernment that’s a key.

When you can discern the fact that getting that Lexus is not going to make you happy and content permanently—you’ll enjoy it for a while. Look at what happens when you buy a new car. The first time you get into that car and drive it home, it’s wonderful. But after a few months or a few years, that car is just the most ordinary thing in the world.

This is the point: that Lexus and nothing else in the world can give you perfect peace and content. This is the discernment. It’s this discernment that changes your behavior, not self-control.

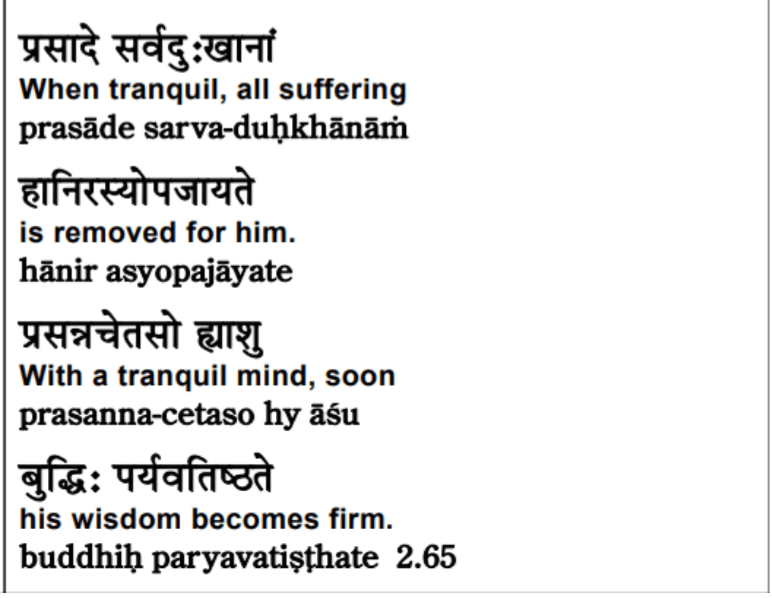

Continue. He talks further about that prasāda—tranquility. He says, Sri Krishna says:

Prasāde—when you have that tranquility, that tranquility born of discernment. For that, in the second line: asya—break the words apart, hāniḥ asya upajāyate. Asya—for that person who enjoys that tranquility, for that person, upajāyate—what arises? What arises is the hāniḥ—the destruction or loss.

The destruction or loss of what? In the first line: sarva-duḥkhānām—the removal of all suffering. For that person who enjoys that tranquility, all suffering goes away.

Why does all suffering go away? Suffering is caused by rāga and dveṣa.

When you feel that sense of, I’m not okay if I can’t get that, if I can’t get a Lexus, I’m not okay. That’s rāga.

Dveṣa—If I can’t get away from this situation, I’m not okay. That conclusion, that feeling, that I’m not okay, I am not content, I am not at peace, unless something changes—that’s suffering.

Nice definition of suffering: suffering is the sense that you are not okay unless something in your situation changes. That’s a fundamental discomfort, an inner discomfort, which ultimately can’t be removed by changing your situation. Because if you change your situation again and again and again, that discomfort keeps coming back. The solution, as we said before, is to discern that your well-being is not dependent on the situation. Your well-being is dependent on your true self, sacchidānanda-ātma, the true source of contentment. And to the extent that you recognize that inner source of contentment, to that extent external situations won’t trouble you at all. They won’t make you suffer.

That’s what Sri Krishna says here: prasanna-cetasaḥ—and for that person whose cetas, whose mind, is prasanna—same root as prasāda—tranquil. For one whose mind is tranquil, and again, a mind that is tranquil through the discernment that nothing outside can truly make you suffer when you appreciate your true nature as sacchidānanda-ātma.

For such a person, he—you have to break the words apart—he āśu, āśu. He—indeed. Āśu—very quickly. Very quickly, for that person: buddhiḥ parayāvatiṣṭhate, parayāvatiṣṭhate.

And buddhi often means mind or intellect, but we’ve used that word in this chapter several times in terms of wisdom. So buddhi here means wisdom, and wisdom specifically—the recognition of the true source of contentment and peace within you.

So for a person whose mind is tranquil—for such a person—they soon become parayāvatiṣṭhate. They soon become well-established in this wisdom.

We had a discussion several classes before that initially this wisdom comes in little glimpses and little insights, where you recognize, at least partially, that the true source of contentment lies within. But then, hours later, you find yourself having forgotten that truth, and you’re back into the usual pattern of being driven by rāga-dveṣa.

A discussion we had in our prior class was the importance of Vedantic contemplation. Next verse is going to talk about it.

Vedantic contemplation, called nididhyāsana, is a particular kind of contemplation or meditation in which you focus on that inner source of peace and contentment. And you focus on it again and again, continually, so that you assimilate that knowledge—that wisdom of the fact that the true source of contentment is within.

That discovery, the initial discovery of the true source of contentment within—that discovery has to be fully assimilated. And Vedantic contemplation—dwelling on that truth again and again—is the means of assimilation.

And in order to perform that nididhyāsana, the Vedantic contemplation, you need a tranquil mind. And that’s going to be explained in the next verse here.

Nāsti buddhir ayuktasya. Yukta here means controlled. Controlled in what sense? Controlled in not being dragged down the slippery slope. Controlled in the sense of not having rāga and dveṣa drag you around. That’s what we mean by being yukta—controlled.

Ayuktasya—for one who lacks that control. For one who is dragged down that slippery slope. For one who is dragged about by the compulsions of rāga and dveṣa. For such a person, buddhi nāsti. Again here buddhi doesn’t mean mind or intellect. Buddhi here means wisdom—this recognition of your true nature as sacchidānanda-ātma.

As long as you’re dragged down the slippery slope, how can you discover the truth of yourself? You need to break free of that compulsivity in order to pay attention in a class like this. If you were completely driven by that compulsivity, someone who is completely driven by that compulsivity would never want to sit and attend a class like this.

So step one is breaking free from that compulsivity so that you can begin this process of spiritual inquiry. So ayuktasya—for one who is unable to break free from that compulsivity—buddhi nāsti. This wisdom will never be gained.

Na ca ayuktasya—and na ca also ayuktasya. For that person who is continually dragged—again ayukta, undisciplined—meaning one who has not yet broken free from that compulsivity. For such a person, na bhāvanā. There is no bhāvanā. Bhāvanā often means meditation. But in our current context, it means specifically—not meditation in general, but that Vedantic contemplation we just talked about. The ability to turn your attention within and appreciate your true self as being the source of contentment and peace. To be able to turn your attention within and appreciate that truth again and again and again.

That’s Vedantic contemplation. That is nididhyāsana—here called bhāvanā.

So for someone who is being dragged about by rāga and dveṣa, being dragged down that slippery slope, there’s no hope for such a person to gain this Vedantic wisdom—discovery of your true nature—nor is there any hope of assimilating this knowledge. If you haven’t gained the knowledge, how can you assimilate it? Makes sense.

Okay. Then: na ca abhāvayataḥ śāntiḥ. Na ca—and also—abhāvayataḥ—for one who is unable to perform this Vedantic contemplation. For one who is unable to assimilate that truth, the truth of your own essential innate nature as sacchidānanda-ātma. For one who is unable to assimilate that truth, there is na śāntiḥ. There is no peace.

Remember: this whole section of the Bhagavad-gita is about the sthita-prajña—one whose prajñā, wisdom, is sthita—firm. And that sthita-prajña is one who has completely assimilated that inner truth, that inner reality, the reality of your own true nature, sacchidānanda-ātma.

So for one who is unable to abide in that truth, there is no śānti. When you abide in that inner truth, there is śānti. When you fail to abide in that inner truth, you are back to the world of suffering.

And aśāntasya—for that person who lacks that śhānti. kutaḥ sukham– How could that person have sukha? How could that person enjoy their life?

Of course, everyone has moments of enjoyment. But moments of enjoyment are interrupted by moments of the opposite. And life tends to be like that: the ups and downs, happy, sad, up and down, back and forth. That gets tiring, doesn’t it?

Every day you are met with new challenges, new challenges to your happiness and contentment. Every day you have to struggle and strive, driven by rāga and dveṣa, to get what you feel that you need and avoid what you feel can threaten you. This is the struggle of life. This is what’s called saṃsāra. Saṃsāra is not just worldly life. It’s the struggle of worldly life. It’s tiring. Notice how at night, in dreamless sleep—in dreamless sleep, you feel perfect contentment. And you might remember from a prior discussion that in dreamless sleep, you’re completely conscious. Your mind is asleep, but ātma—consciousness—continues to shine as much as it does right now while you’re awake. The point here is: in that state of dreamless sleep, you feel perfect contentment because there’s no struggle. There’s no constant striving. That constant striving is suffering. To be able to—let me make this very clear: the goal of life is not to sit in a chair, blissed out, or to lie down in bed, blissed out, in deep sleep. That cannot be the goal of life. The goal of life is to be engaged in your daily activities, but without that sense of striving, without that compulsivity involved, so that everything becomes effortless in life.

For the sthita-prajña, one whose wisdom is firm, life ceases to be a matter of striving. Life becomes effortless. Effortless in the sense that you appreciate your innate fullness and completeness. No effort is required for the sake of your own contentment and peace.

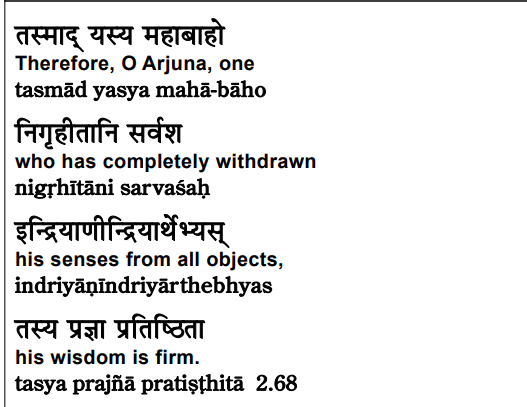

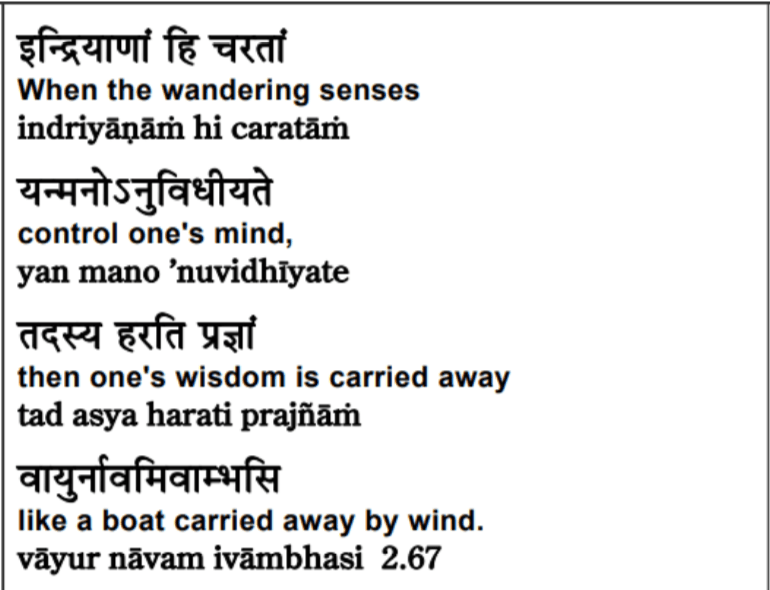

Then, here we get the counter-example. A very common way of teaching is to give the counter-example: what happens when things go wrong?

When things go wrong, Sri Krishna says:

Indriyāṇām hi caratām, hi indeed. Caratām—when there is the movement indriyāṇām—of the senses. Again, indriyāṇām—senses here doesn’t just mean your five senses, but the mind and senses.

So the first quarter of this verse: indriyāṇām hi caratām—when your mind and senses are constantly active, constantly engaged in striving. Striving to get what you think is essential for your well-being. Striving to avoid what you think is harmful to your well-being.

Yan mano anuvidhyate When your mind—Yan mano when the mind is anuvidhyate—is controlled. When the mind is controlled by the wandering senses. My translation is not exactly faithful here. Anuvidhyate is passive voice, and my translation is active voice—for Sanskrit students.

So when your mind is dragged about—I like that language—when your mind is dragged about by your senses. And you see something that looks like you think is important for your well-being, you’re compelled to chase after it. When you see something that threatens your well-being, you’re compelled to run away from it. This is what I mean by your mind being dragged about by your senses.

Arasya harati prajñām. Asya—for that person. For that person, harati prajñām—that person’s prajñā, wisdom, harati—now I’m getting back, I’m having a problem with active and passive voice. I’ll spare you all the grammatical details.

Tatt harati prajñām. Tatt—that mind which is being dragged about by the senses. That first tatt is that mind which is being dragged about by the senses. Harati—carries away, robs away, asya prajñām—a person’s wisdom.

And the wisdom we’re talking about here is the wisdom of these teachings. These teachings which tell you that nothing in the world is capable of giving you perfect peace and contentment.

When that wisdom is robbed away by your senses, when the mind gets dragged about, then—turning it around, sorry—when your mind gets dragged about by the senses, then that mind grabs away your wisdom. Or, to put it in simple terms: your wisdom, whatever you’ve understood in these classes, gets overcome, overwhelmed, set aside, robbed away by a mind that is unstable.

That’s the theme of this part of chapter 2—sthita-prajñam. When your wisdom is not firm, your understanding can get shaken, and you will end up in a state of suffering once again.

But when your wisdom is firm—due to step one, the discernment we’ve discussed several times, and step two, that Vedantic contemplation, nididhyāsana, that process of assimilating this wisdom, of internalizing it very completely—for such a person, their wisdom is never carried away.But until and unless that happens, you are subject to being swept away.

And Sri Krishna gives a nice metaphor here about being swept away: vāyuḥ, nāvam iva, ambasi.

Iva—just like. Navam—a boat. Ambasi—on waters. A boat in the sea gets swept away by what? Vāyuḥ. Vāyuḥ—winds—sweep a boat away.

A boat without a paddle and without a sail—if you don’t have a paddle and you don’t have a sail, you are helplessly swept along by the wind. That paddle and sail represent the discernment that we are gaining through these teachings.

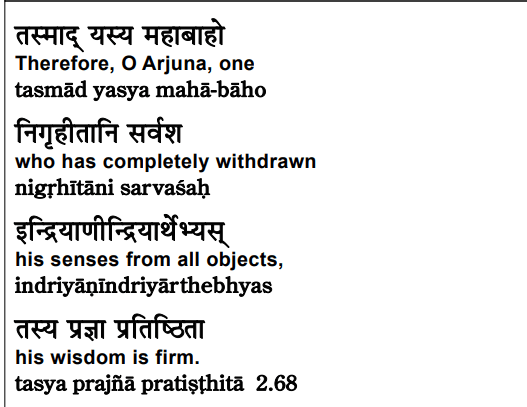

Then this whole section concludes with this next verse. Let’s see that.

Then this whole section concludes with this next verse. Let’s see that.

Mahābāho. Mighty-armed Arjuna.

By the way, Mahābāhu is “armed.” Mahābāhu—there’s some place that actually describes that. Mahābāhu—one who is mighty-armed. They say that your bāhu is ājānu. Jānu is knees. So one whose arms extend down to the knees. That’s a funny expression. I don’t think that’s physiologically possible for human beings, but that’s how it’s described in one place.

Mighty-armed is a common expression for Arjuna and other warriors.

O mighty-armed Arjuna, tasmāt—therefore. Therefore, Arjuna—and this is a big tasmāt, a big “therefore.”

Yasya—for such a person. Now drop down to the third line: for such a person whose indriyāṇi—whose senses, and again, senses and mind. For a person whose senses and mind are, in the second line, controlled, restrained—sarvaśaḥ, completely, in all manner.

For a person whose mind and senses are completely controlled, and back in the third line, indriyārthebhyah—restrained from sense objects. Indriyārthebhyah. Artha—sense object, and like our Lexus.

So for a person whose mind and senses are completely restrained from being compelled—and here’s the point—the problem is that compulsion. To break free from this compulsion is what we’re after. You know that the goal of spiritual life is called mokṣa. Mokṣa means freedom. And not just freedom from rebirth—inner freedom.

Inner freedom means freedom from suffering. Inner freedom means freedom from this compulsion. This compulsion to chase after whatever you think will make you feel happy, and this compulsion to run away from anything that you think will make you unhappy. To be freed from that compulsion is inner freedom—that is mokṣa.

So for the person who’s yasya—yes, for that person whose indriyāṇi, mind and senses, are sarvaśaḥ nīgrahītāni—completely restrained. Indriyārthebhyah—prevented from being compelled to chase after or run away from worldly things. For such a person, tasya—for such a person—prajñā—that person’s wisdom is pratiṣṭhitā—firm.

That person is well established, firmly established in this particular wisdom—the wisdom that your essential nature is the true source of contentment and peace.

And just one more point—I want two points I want to make here before we conclude.

First is we have these two steps. Step one is discernment. Step two is assimilation. First you discern the inadequacy of worldly pleasures to bring you perfect peace and contentment. You further discern that the true source of peace and contentment is within.

That’s step one: discernment.

Step two: assimilation. Your mind has to be deeply ingrained in that understanding, in that wisdom. And this takes place with the help of nididhyāsana—Vedantic meditation, a process of assimilation.

The example that’s so often used for this process of assimilation is when you make this typical Indian sweet called rasagullā. So the gullā is a ball of cheese. And that cheese ball has to be immersed in rasagullā. Here rasagullā is a sugar syrup—sweet syrup.

So these balls have to be immersed in that syrup not just for a few minutes, not just for a few hours—at least overnight. Only when you leave those balls immersed in that syrup long enough, only then do they soak up all that sweetness.

That describes this process of assimilation.

So the process of assimilation that’s important here is to become immersed in the understanding that your true nature is already full and complete. That’s the inner divinity. To be immersed in that wisdom—knowing your own inner divinity. With this complete immersion in that wisdom, what happens to that compulsivity? It’s gone. Completely gone.

The final point to make here is that this freedom from compulsivity—I’ve made this point before, I’ll just make it one more time here because it’s important. This freedom from compulsivity is not an act of will. You’re not restraining yourself from running to the auto dealer to buy a Lexus. It’s a matter of discernment. When you understand that a Lexus is not going to be a permanent source of contentment and peace—that discernment is sufficient.

Again and again, Sri Krishna talks about restraint: nīgrahītāni indriyāṇi—when the senses are restrained, senses and mind are restrained.

Be very clear: this restraint is not a matter of will—which is a good thing, because none of us have perfectly strong wills. Our willpower can be so strong, but when something is stronger than our willpower, we get overwhelmed. Your willpower can be very high, but then something can be higher than your willpower—you get overwhelmed.

The solution is not in developing your willpower. The solution is developing this discernment and assimilating this wisdom.

We’ll stop here. There are a few verses left. In fact, I think in the next class we’ll be able to finish chapter 2.

But before that—next week our ashram, our Arsha Bodha Center, will be celebrating our 21st anniversary. It’s amazing to think that 21 years have gone. They’ve gone by very quickly.

Anyway, it’s a wonderful celebration for us. Usually our anniversary celebrations are big. We have hundreds of people here, and the guests, and nice program presentation, and some nice food that follows the celebration.

Of course, we’re still locked down like everyone else due to the pandemic. Our celebration will be a virtual celebration, a webcast. And specifically next week, next Saturday, instead of our Bhagavad-gita class, we’ll have a webcast of our anniversary celebration.

So please join us next Saturday at the same time for our webcast of our anniversary celebration. And then the following Saturday, we’ll resume our study of the Bhagavad-gita. Then we’ll continue.

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ असतो मा सद्गमय ।

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय ।

मृत्योर्मा अमृतं गमय ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Asato Maa Sad-Gamaya |

Tamaso Maa Jyotir-Gamaya |

Mrtyor-Maa Amrtam Gamaya |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om, (O Lord) From (the Phenomenal World of) Unreality, make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the Reality (of Eternal Self),

6: From the Darkness (of Ignorance), make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the Light (of Spiritual Knowledge),

7: From (the World of) Mortality (of Material Attachment), make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the World of Immortality (of Self-Realization),

8: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om, Tat Sat. Thank you.