Gita Class 020, Ch. 2 Verse 59-63

May 22, 2021

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLeP4eulMEXiOC8DjxjFc2Vt1yEtD8IAbl

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

Welcome back to our weekly Bhagavad Gita class. We continue our study of chapter 2. We’ll begin as always with some recitation. Please be sure to look at the meaning as you listen to me and then repeat after me.

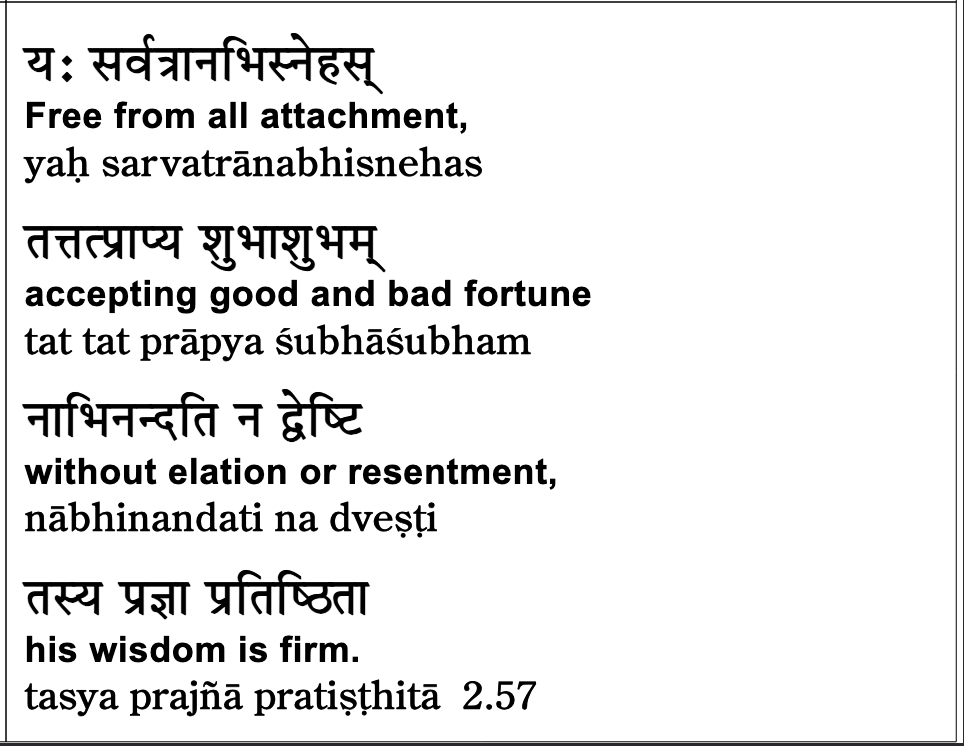

We’ll start our recitation with verse 57.

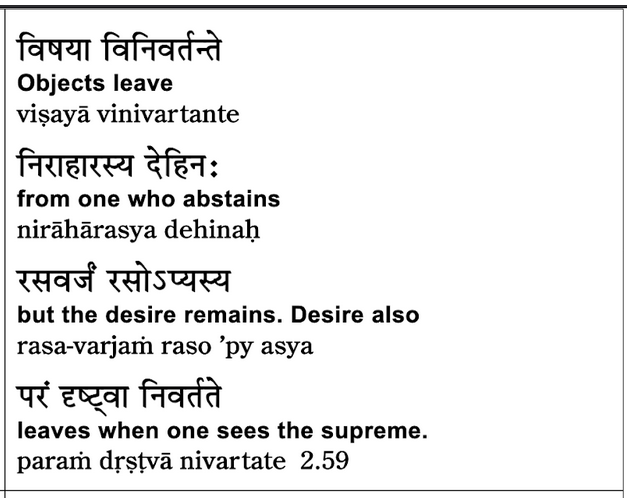

Very good. We’ll return to where we left off in the last class. We finished verse 58. We’ll continue at 59.

Some 58 I want to show you. Our context here, of course, is called the Stithapragya Lakshana, the part of the second chapter which contains the Lakshana, the characteristics of the Stitta Pragya. One whose Pragya, spiritual wisdom, is stitta, firm. Sri Krishna’s teachings here come in response to Arjuna’s question: How does an enlightened person sit and walk and talk and so forth?

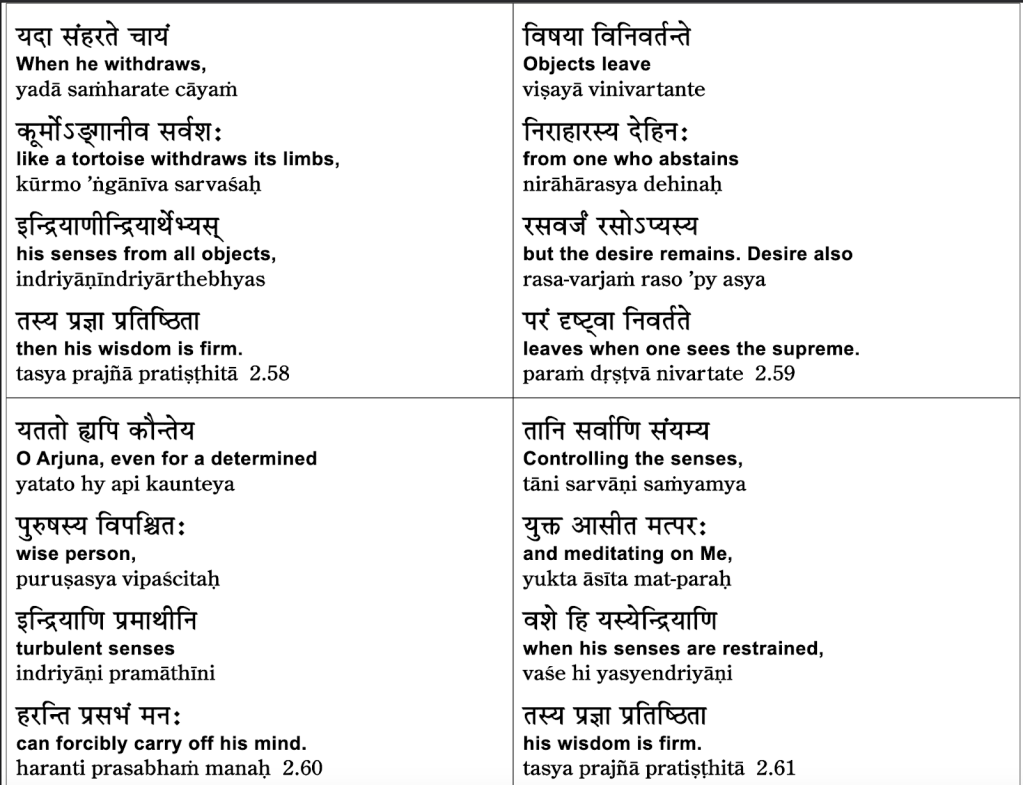

In our last class, we saw that wonderful metaphor in verse 58, that the stitta Pragya is compared here to a tortoise, which may seem a little bit odd. The point is that a tortoise, when frightened, doesn’t need to run away; it simply withdraws its limbs. As I said in the last class, it’s five limbs—two arms, two legs, and one tail—represent our five senses, sight, hearing, taste, touches. The tortoise’s head, of course, represents our mind.

So Sri Krishna says, just as a tortoise withdraws all six of these appendages, so too the enlightened person withdraws from the world. Now, there’s some confusion about this withdrawal. I explained in some length in our last class that the enlightened person is one who knows that the true source of peace and contentment and happiness is within, so it makes sense for the enlightened person to turn his or her attention within and withdraw the attention from the world around.

But that withdrawal gets misinterpreted—not only in the Hindu tradition, but especially in the Hindu tradition—because of the emphasis on asceticism, the kind of living a life of tapasya, austerities. And the prototypical image is the fellow who goes and lives in a cave in the Himalayas. And that act of withdrawing from the world and going and living in a cave in the Himalayas, that image is held with such esteem in Hindu culture—and that actually becomes a problem. Because the typical story is that somebody, a man, middle-aged man in some town in India, is struggling in life: lost his job, he’s fighting with his wife and other family members. He has a problem with drinking, and the guy is really in bad shape, and then he disappears. Doesn’t come home one day, no one knows where he is. Months later, some relative happens to find this fellow living in an ashram in Rishikesh. Not an uncommon story.

To withdraw from the world because you’re so miserable is not what this is describing. It’s not that the tortoise is miserable then it draws—it’s actually the better example is the wise person. The wise person withdraws mind and senses and focuses one’s attention within because within is the true source of happiness and contentment. This fellow who ran away from his town and his family, who is living in an ashram in Rishikesh, he’s not finding contentment. In that ashram, his room is like a cell in a prison. Prison. In fact, I have to tell you, the first time I went to Rishikesh, the room I had—my first visit to India. The rooms, many of you know this, rooms are often furnished with windows, with bars on the windows. Of course, the bars are to prevent theft, also to prevent monkeys; a lot of monkeys around. The bars are there to prevent theft and monkeys from entering, but when I saw the bars on the window of my room in Rishikesh, I thought it looked like a prison.

So that fellow who goes to Rishikesh, he’s living in a prison cell. Further, he had all these problems in town. When he goes to Rishikesh, he inadvertently brought all his problems with him. All the problems are in his mind. He’s sitting in his cell in Rishikesh, thinking about all his problems. What’s positive about that? Why should that be held in high esteem?

Just the final—I have to share with you one more story about this, just to illustrate. Netto withdrawal that we’re talking about here is not a withdrawal from ordinary daily life. It’s a withdrawal from being focused on external things and people for the sake of your happiness and contentment and turning your attention within.

One last story about going back to living in a cave: again, when I was living in Rishikesh, I took a trip up into the hills surrounding Rishikesh. It was about a half a day walk up into the hills, and I went to meet one, one, Mouni Baba, someone who literally lived in a cave and maintained perfect silence. When I finally got there—long walk—when I finally got there, I was shocked and stupified, to use a very big word, because this Mouni Baba was sitting outside of his cave, reading a newspaper.

Now, what’s the point of going and living in a cave if you’re going to bring the city with you in a form of newspaper? What kind of withdrawal is that? This is not withdrawal; it’s a kind of hypocrisy. And that kind of hypocrisy is what Sri Krishna talks about in this next verse, which we will see. Excuse me.

When I said a kind of hypocrisy, that might be a strong word, but it fits because hypocrisy is to do one thing, but to have something entirely else in your mind and heart. So that fellow who went and lived in the cave, inside his mind and heart, he was not withdrawing. He kept the newspaper with him.

And here, Sri Krishna uses a more general approach to that. He says, someone—second line—Nira Harasya Dehinaha. Remember, we saw that word Dehina, Dehi, one who has a body, the indweller of the body. Here it simply means person. Dehinaha, an embodied person, who is Nira Harasya, one who has withdrawn. Aharas, what you take; Nira Haras is without taking anything with you. That would include food, drink, all kinds of enjoyment—one who withdraws from worldly pleasures.

For such a person, first line, Vishayaha—objects, but specifically, objects of pleasure, objects of enjoyment—Vinivartante, they go away. The person who goes to live in a cave or withdraws from worldly pleasures, for that person, Vishayaha, objects of pleasure, Vinivartante, go away.

Rasa—and the third line, Rasa Varajam, except for Rasa. Now, Rasa is a tricky word because it has so many meanings. It must have much, many more than 10 or 12 meanings in the dictionary, if you look it up. Here, Rasa, the general meaning is like sap or essence, and it can mean taste. But here, it means desire. It—desire is the meaning for the word Rasa here.

So the person who withdraws, Nira Harasya—for that person who withdraws—Vishayaha Vinivartante, objects of enjoyment go away, Rasa Varajam, but desire for those objects of desire don’t go away.

Several classes ago, I gave the example of someone who decides that drinking tea is not spiritual. So they stop drinking tea, and there’s no more tea. But the desire for tea continues. In fact, the desire for tea can even grow stronger. If you’re in a habit of drinking tea several times a day and you suddenly stop, the desire for tea, in fact, will grow stronger.

So, Rasa Varajam: you can give up objects of desire, but you cannot give up desires. I’ll say that again. You can give up objects of desire; you cannot give up desires. You can overcome desires, but you can’t just decide, okay, I’m going to stop desiring tea. You can choose to stop drinking tea. You cannot choose to stop desiring tea.Then how do you get rid of those desires? That’s what Sri Krishna says in the second part of this verse. Ape. So in the first half of the verse it says, you give up the objects of desire, but Rasa—the desire for those objects—continues. But here, in the second half, Sri Krishna says, Asyah—for another person, in fact for an enlightened person. How do we know we’re talking about—by the way, you have to break all those words apart. Rasa ha Api Asyah—in the third line. Asyah, for an enlightened person.

Why an enlightened person in the third line? Param Dhristwa. Dhristwa, having seen, having discovered Param, the ultimate, the supreme truth, the truth of your consciousness being utterly non-separate from Brahmin, the reality because of which the universe exists—this discovery that leads you to enlightenment.

So, Asyah, for that person, Paramdhristwa—who has discovered that inner truth—for such a person, Rasaha Api desire also, Nivartate, goes away.

Let me paraphrase the whole verse: for an enlightened person who simply withdraws from worldly pleasures, the desire for those worldly pleasures continues. But for an enlightened person—listen carefully—an enlightened person, Param Dhristwa, an enlightened person who has looked within to discover the true source of happiness and contentment, Atma, Satcharananda—for such a person who has discovered the true source of contentment and peace within—for such a person, Rasa ha Ape, Nivartate, any kind of desire for worldly objects also goes away.

When you discover your own innate fullness and completeness, that’s when desires go away. Desires do not go away as an act of will. You can’t choose to make desires go away. How do you overcome desires? By discovering that the true source of contentment and peace is within you, and that inner contentment and peace doesn’t depend on that external object.

When you discover that, even in the absence of Tea, you’re absolutely content and fine. Excuse me. Excuse me. Wrong side. Sorry. When you discover that your contentment doesn’t depend on Tea, your desire for it goes away. Whether you choose to give it up or not, your desire for Tea goes away the moment you discover that your contentment doesn’t depend upon it. That’s for the enlightened person in the second half of the verse.

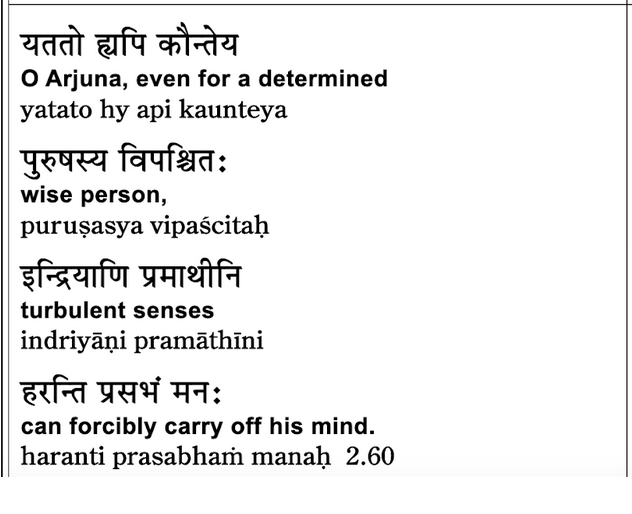

Okay. Then, Satchar begins a new topic here. The new topic is how powerful desires are, how powerful our mind and senses are in pulling us one way or the other. It goes on for quite a while. I mean, maybe half a dozen verses. Let’s begin this new topic.

In the second line. What kind of person? Vipaschita—for a wise person, for an enlightened person, for an enlightened person.

First line. Let me see that. He, he, he, he, hy—even, even for an enlightened person. Kaunteya, O Arjuna, O Son of kunti—even for an enlightened person. Yatataha, even for an enlightened person who strives, an enlightened person who strives—and the context is withdrawal. Going back to our tortoise metaphor: an enlightened person who strives to turn one’s attention away from worldly pleasures and to turn one’s attention within towards the true source of contentment and peace.

So, even for an enlightened person, Yatataha—who strives—Indriani, Prmathini. Indriani, the senses. And the senses in general are not five, although we generally count five senses, but the mind is often counted as the sixth sense. In fact, mind is called Anta Karana. Karana means sense organ. Antaha, the internal sense organ. You have five senses which look outward into the world: sight, hearing, tastes, smell, and touch. Are those five? Those are outward-focused senses, and you have one focus, AntaKarana—mind—which is inward-focused.

So, those six senses are Prmathini. They are turbulent. They are always active and they’re hard to control, which is what Sri Krishna says, that those turbulent senses, Haranti—they carry away literally. They carry away Manaha, the mind. They carry off your mind, Presubham, forcibly.

You all know the expression, when your mind gets carried away by something or another. You know that experience. You know how powerful the mind is to get attracted to something and to be distracted by something.

I think about students who study and how easily it is for a student—a student who has books all over the desk. They’re studying and studying, and then their phone is there. They pick up that phone and in two minutes they’re texting, they’re browsing the internet, they’re doing all kinds of things. That phone is such a distraction for the student. Well, everyone has such distractions in their lives, and the surprising thing in this verse is Vipashchita—even an enlightened person, at first, can be forcibly distracted by the mind. Notice I said at first. The moment you discover that inner source of contentment and peace, it would be unreasonable to assume that with that initial discovery, 100% of your thinking instantaneously changes. You all know how habitual our minds are, and that applies even for an enlightened person.

An enlightened person—let’s make it concrete—a person who really likes tea. First thing in the morning, has to have that cup of tea. Later in the morning, another cup of tea. And if the tea is late, this person gets irritated or something.

Imagine this person gets enlightened. Getting enlightened means to look within yourself and discover that the true source of contentment and peace is within. So this newly enlightened tea lover realizes that tea is not necessary for the sake of one’s contentment. But this tea lover has been so fond of tea for decades—even after discovering the true source of contentment and peace within—the next morning, on one evening they get enlightened, the next morning you can be sure this tea lover will be looking for a cup of tea, even though he or she is newly enlightened.

What’s going on? The habitual nature of the mind. Of course, that tea lover, if they will just take a moment, if the tea is not available the next morning, then the tea lover will quickly reflect on the fact that, “Oh, I guess I really don’t need the tea. After all, I am Sat Chit Ananda Atma. Sat Chit Ananda Atma doesn’t depend on a cup of tea for being content and at peace.”

But before making that reflection, this newly enlightened tea lover felt that pang of urgency: Where’s my tea? Where’s my tea?

That is what Sri Krishna is describing here. Indriyani Pramatini—the senses are so turbulent, even for this enlightened person, that Haranti Manaha—they can rob away this person’s mind forcibly, even just for a moment.

But in that moment, there’s a moment of suffering, that moment of urgency: Where’s my tea? Of course, that moment passes very quickly, but it shows even an enlightened person at first is subject to such disturbances.

I’ve noticed I’ve said a couple of times now at first because there is a specific practice which is used to overcome that habitual nature of the mind. This is a technical topic. I don’t want to go deeply into it. Some of you have heard this topic before, so let me just refer to it by its name.

It is said that—not “it is said,” it’s just a fact—that immediately after you are initially enlightened you almost certainly suffer from a problem called Viparita Bhavana. Viparita Bhavana is this habitual thinking which is contrary to the truth that you’ve discovered.

So for that enlightened tea lover to feel that momentary pang of urgency, Where’s my tea?—it’s an example of Viparita Bhavana. It goes away. But even for that moment, it comes, and that moment is a moment of suffering.

So there is a specific practice to remove that Viparita Bhavana, that habitual thinking which is not consistent with the wisdom a person has discovered. That practice, as some of you know, is called Nididhyasana. Nididhyasana is Vedantic contemplation.

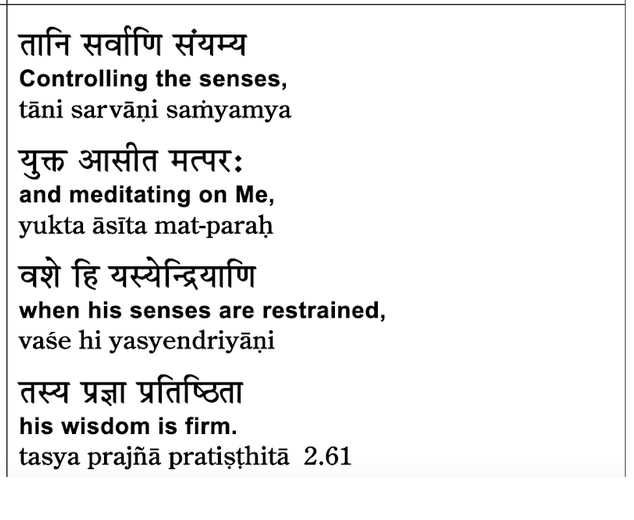

We’re not going to go into it deeply here, but Sri Krishna makes a reference to that practice of Nididhyasana in the next verse. Let’s see.

Viparita Bhavana is the ultimate practice of the mind. So that newly enlightened tea lover who feels this momentary pang of sense of urgency, Where’s my tea?—what should that tea lover do?

Sri Krishna gives some instructions here: Tani Sarvani Samyamya. Tani Sarvani—all of them. All of what? All of those senses, and senses are six in number: sight, hearing, taste, touch, and smell are the five, plus one—the mind, Antakarana.

So those six senses, Samyamya—withdrawing those six senses—and Yukta Asita. Asita, remaining. Remaining Yuktaha, engaged. Remaining engaged, and also has a sense of practice of yoga, practice of meditation. You can see it comes from the same root as from which the word yoga comes.

Yoga has many meanings. Here Yukta Asita—that person should remain engaged, and remain engaged specifically in meditation. How? Mat Paraha. Sri Krishna says very clearly, Mat Paraha—being focused on me. Mat Paraha means being focused; Mat is a pronoun form of “me,” being focused on me.

So that person, our newly enlightened tea lover who suffers from this Viparita Bhavana, this habitual thinking which causes moments of suffering—what should that newly enlightened tea lover do? Samyamya—having withdrawn Tani Sarvani, the mind and senses. Yukta Asita—that person should remain in meditation, Mat Paraha, focused on me.

Now, in chapter two, when we come to chapter six, Sri Krishna is going to talk extensively about meditation. After all, chapter six is Dhyana Yoga—it’s the chapter on Dhyana, on meditation. And Sri Krishna is going to describe his preferred practice of meditation—the practice of meditation he prescribes to Arjuna—and that practice is to focus on God’s presence within you, Ishwara’s presence in your own heart.

And Sri Krishna, of course, is speaking here in the role of Ishwara, from the standpoint of Ishwara. So he says Mat Paraha—to be fixed in meditation, Mat Paraha, focused on me. And contextually, that means focused on Sri Krishna’s presence within your own heart and mind—that divine presence within you.

To be focused on—and to use simple language—to be focused on the inner divinity. And how clear this is, because when you are focused on that inner divinity, you are focused on the true source of contentment and peace. And to the extent that you’re focused on the true source of contentment and peace within you, who cares about a cup of tea? When you discover that inner fullness and completeness, that tea becomes such a trivial thing, absolutely unnecessary.

So here, Sri Krishna is, in very casual terms, we’ll say, referring to a kind of Nididhyasana. We translate as Vedantic contemplation. And Sri Krishna here describes it as meditating on the—literally—on his presence within you, or in a more general sense, meditating on the inner divinity, meditating on the true source of peace and contentment within you.

Vashayi, Yasya, Indriyani, Yasya—in the third line, sorry—Yasya, for that person. Indriyani Vashe hi, when that person’s senses are Vasha, controlled. Vashe hi, when those senses are controlled. And again, senses means five senses and mind.

When, for that person, through that practice of meditation—focusing on the divinity within you, the true source of peace and contentment—for that person who controls, who brings the mind and senses under control by that practice of meditation on the divinity within you: Tasya Pragya Pratishtita.

Tasya, for that person. Pragya—that person’s wisdom. Pratishtita—that person’s wisdom is firm. We’ve seen this expression in prior verses: Tasya Pragya Pratishtita. Such a person’s wisdom is firm. Such a person is a Tasya Pratishtita Pragya.

All right.

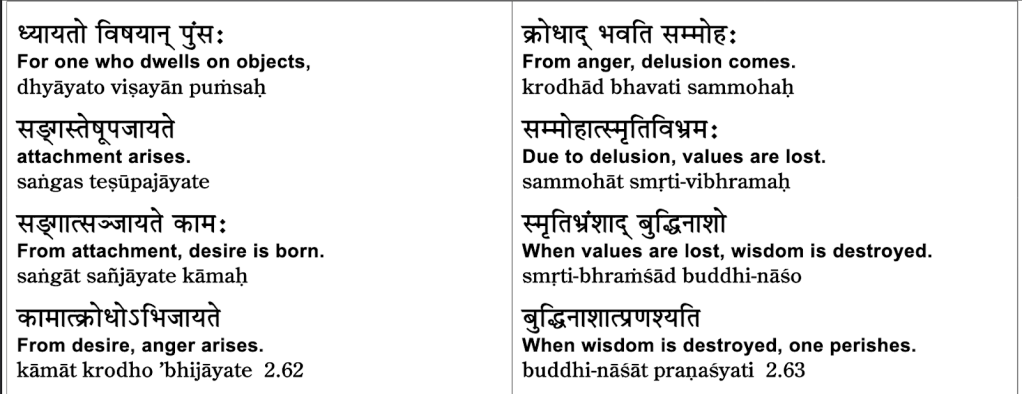

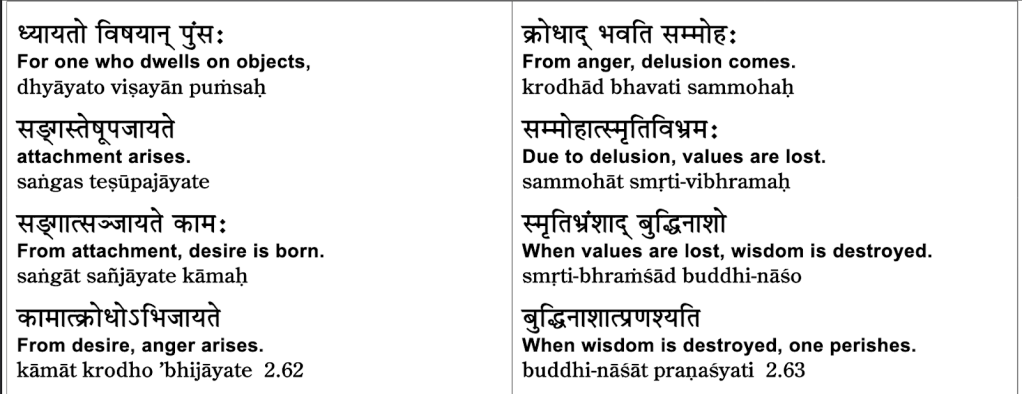

Continuing to talk about how powerful the senses are, we have a pair of verses here:

These two verses are connected, so we saw them together. These two verses give a series of steps, as it were, through which your mind gets carried away.

Your mind doesn’t get carried away instantly. It goes from A to B to C. In fact, in these two verses there’s a series of eight steps. Four steps in each verse. Every verse has four quarters, and each quarter of these two verses is going to give one step. A step in which you are carried—a carried, they call it a slippery slope.

You know that expression? Slippery slope is when one error leads to another error, leads to another error, leads to yet another error. And pretty soon these errors accumulate, leading you on that path of Adharma.

That’s really what’s described here: a series of errors, each step we’re going to see, eight steps, eight errors in thinking, which carry you into a path of Adharma because of the mind’s nature. The mind having that nature, the capacity to rob you—that term we saw in the prior verse: Haranti Manaha. It literally robs your mind.

Instead of “rob,” I like the sense of hijack. Imagine your mind being hijacked. Hijacked by what? We’ve had discussion before. Hijacked by—they’re two hijackers: Mr. Raga and Mr. Dvesha.

Remember our definition: Raga is a compulsion to chase after something you want, something that you believe to be essential for your happiness and contentment. Dvesha is also a compulsion—a compulsion to run away from something that you think will obstruct your pursuit of happiness and contentment.

So these two are the hijackers: Raga and Dvesha, which literally rob away your mind. Hijack your mind. And the process of hijacking is described here in great detail. It’s actually a bit of psychology. There’s a surprising amount of psychology in the Bhagavad Gita.

And we’ll see that here in the series of verses.

Dhyayataha Vishayan Pumsaha. Pumsaha, for a person who is Dhyayataha—could mean meditating, but you don’t get the right meaning here. Meditating meaning dwelling. Dwelling on what? Vishayan—for a person who goes on dwelling on objects.

Now, to explain these two verses, it’s helpful if I give a concrete example. And we’ll take that example all the way through. And the example—some of you, if you’ve heard me teach these verses before, you might remember me using a Lexus car as an example. And it could be any really expensive, fancy car.

So here the example goes like this: imagine a person who sees a commercial for this Lexus car, very fancy and costly car. And he doesn’t just see one commercial. Every time he turns on the TV, he sees another Lexus car commercial. Commercial, commercial, Lexus, Lexus, Lexus.

So this is what the first line is talking about. Dhyayataha, Vishayan, Pumsaha—for a person who is constantly exposed to some object. In this case, the object is a fancy car.

For that person, in a second line, Sangaha, Teśu, Upajaya, Teh. For such a person, Sangha—here Sangha means attachment. Teśu—towards the objects that this person has been exposed to, Upajayateh—arises.

When that person is constantly exposed to those Lexus car commercials, for that person, Sangha, attachment arises. Remember our definition of attachment. I’ve said several times: attachment is emotional dependence.

When you look upon that external thing or person as being essential for your well-being, that’s attachment. That’s emotional dependence. You are emotionally dependent on someone or something for your emotional well-being. That is Sangha, that is attachment.

So when this person sees one Lexus car commercial, nothing much happens. But after a dozen Lexus car commercials, this person begins to think, A Lexus car would make me happy. That’s attachment: A Lexus car is important for my happiness and well-being. Before the commercial, this person didn’t have that thought.

By the way, just to tell you something you all know: the purpose of advertising and commercials is to instill in your mind desires for things you never desired before. What an odd way of looking upon it, but that’s exactly what advertisement is all about. It’s something you’ve never had a desire before—advertisement and commercials can instill in you a desire.

But here, instead of going to desire, we’re seeing the step prior to desire. There is a step prior to desire. First step is to be exposed to that object again and again. Second step, Sangha. You get attachment. Attachment is the conclusion that that object is important for my well-being. That is attachment, that is emotional dependence.

Sanghat, and from that attachment, here comes the third step. From that attachment, Sangha, what arises is Kama—desire.

Notice the detail in these verses. This desire is being analyzed into two parts. First part is the conclusion that something is essential for your emotional well-being. And the second part of that is that you desire it. The moment you feel that something is essential for your well-being, you will instantaneously desire that thing.

So attachment and desire are so deeply connected, but you can see the difference. Attachment is to consider something essential for your well-being, and desire is, as you know very well: I want it.

Kamaat, and then comes the next step. The fourth step, Kamaat. From desire, Krodha Abhijayate—anger arises in the fourth step. And that might not seem obvious at first. How does anger arise from desire?

Because—stay with our example—you want the Lexus , but you can’t afford it. For every desire, there will be certain obstacles, and those obstacles will lead to anger. In fact, my guru, Pujuswami Dayananda, once defined anger in a very unique way. He said, Anger is obstructed desire. Interesting definition.

You can see the psychology here. Anger is obstructed desire. You have a desire, but you can’t get what you want. So, due to the obstruction preventing you from fulfilling your desire, you experience Krodha—the fourth step.

Then, the fifth step: Krodha. From anger, Bhavati—what arises is Samoha.

Samoha—commonly translated as delusion—but in our, in our, to stay with our example, a good way of seeing this delusion would be scheming. How? I can’t afford a Lexus , so how can I get one? That scheming, that kind of obsession. Samoha can also mean obsession. You become obsessed with something, constantly thinking about it, and then thinking not just about how much you want it, but thinking about How can I get it?

So, that’s a scheming. And so, that is the fifth step. Krodha Bhavati—what arises from anger is Samoha: delusion, delusion in a form of being obsessed with it, and even leading to the scheming: How can I get it?

Then, the next step: Samoha. And from the scheming and obsession, from this delusion, what arises next is Smriti Vibramaha.

Vibramaha means loss. Smriti generally means memory. And if you translate this literally, it doesn’t make any sense at all. You don’t lose your memory due to this delusion. It’s a little obscure. But Smriti—memory—is a word that’s used to describe your assimilated values.

You have a value for honesty, a value for following Dharma. These are values that you hold in your mind and heart. They’re values that are deeply ingrained in you, that you received from your parents and other authority figures. So these deeply ingrained values here are called Smriti—not really memories, but better described as deeply assimilated values. Values for honesty, values for being truthful, values for following Dharma.

And what happens—and what Shri Krishna is describing here—Samoha, but due to this obsession and scheming and delusion, Smriti Vibramaha—your values are lost. Values not lost—maybe it literally says lost—but overwhelmed.

You know that when you’re obsessed with something, you can be led to do something that you know is wrong. That’s the power of delusion, the power of obsession. So in terms of our example: the scheming. This person wants a Lexus , can’t afford it, and is scheming, and comes up with a scheme maybe to embezzle money from the workplace—to steal.

So the person has a value for following Dharma, but due to this obsession and delusion—Samoha—that value for honesty and not stealing gets overwhelmed. That is Smriti Vibramaha: values are overwhelmed, values are forgotten.

Then comes the next step, step seven: Smriti Vibramshat. And when your values have been overwhelmed by your delusion and set aside, then what happens next is Buddhi Nashaaha.

Smriti Vibramshat—due to your values being overwhelmed by obsession—the seventh step, what happens next is Buddhi Nashaaha. Nasha means destruction. Buddhi—of your intellect.

And again, literal translations don’t make sense. Not that your intellect gets destroyed, but your intellect—here’s a sense of destruction—your intellect is supposed to keep you on the path of Dharma. That’s one of the—how do you follow Dharma? By using your Buddhi, by using your intellect, by using your reasoning to discern what is right and what is wrong in a particular situation.

Here, Buddhi Nashaaha means not literally destruction of your intellect, but perversion of your intellect, in a manner of speaking. Your intellect, Buddhi, which is supposed to be used to keep you on the path of Dharma—that intellect is used to take you off the path of Dharma.

So you’re scheming on how to embezzle money from the workplace, and your intellect gets engaged in that Adharmic activity. That’s what Buddhi Nashaaha here means. Your intellect is destroyed in the sense that your intellect gets engaged in Adharmic activities. The intellect that’s supposed to keep you on the path of Dharma—that intellect gets engaged in Adharmic activities.

And that leads to the final step: Buddhi Nashaaha. And when your intellect is engaged in Adharmic activities—Pranashyati—the person is destroyed. Very strong language. Kind of poetic.

Person is destroyed. I guess, to finish up our story: the person embezzles, uses the intellect which is supposed to keep you on the path of Dharma. The person uses that intellect to figure out how to embezzle money from the workplace. And of course the person gets caught and sentenced in a courtroom and sent to jail. Pranashyati—the person is destroyed. The person wanted a Lexus , and what the person got was a jail sentence. That’s what it means here to be destroyed.

So notice this set of eight steps—this so-called slippery slope. Let’s review it briefly before we move on.

The first step: Dhyayataha—to go on dwelling upon an object, an object of pleasure, we’ll call it. Dwelling on an object of pleasure leads to what? Sangaha—attachment. The conclusion that that object of pleasure is essential for your emotional well-being. Attachment.

And that attachment leads to what? Sangha—attachment leads to Kama. Kama—desire. I want it.

And Kama, of course, leads to Krodha. I want it, but I can’t get it. Therefore, I’m angry.

And Krodha leads to Samoha—this obsession. I have to have it. How can I get it? And the scheming.

And that Samoha—delusion and scheming—leads to Smriti Vibramaha. Your values get overwhelmed, get overcome.

And when your values are overcome, in the step seven, Buddhi Nasha—your intellect, which is supposed to keep you on the path of Dharma—that intellect is employed in Adharmic activities.

And the final step, Buddhi Nasha—when your intellect gets involved in Adharmic activities, Pranashyati—your life gets destroyed.

So these eight steps describe how your mind gets hijacked, how you get carried away. Step by step. Notice a tremendous psychology—psychological principles, so many important psychological principles are really evident in this series of verses.

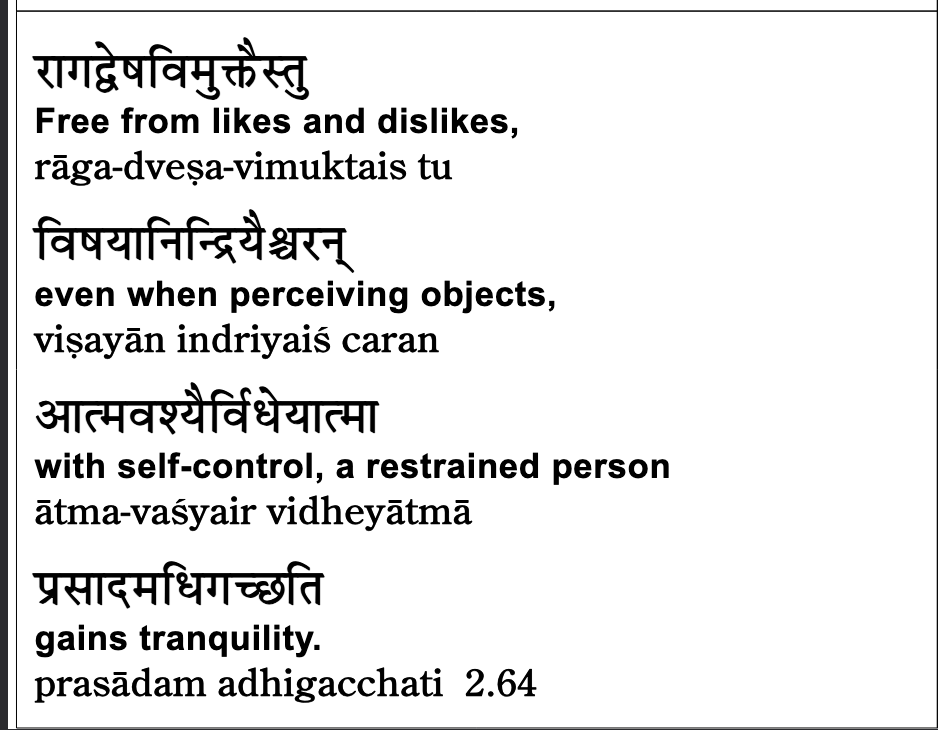

Now, we’ll see one more verse. But to introduce that verse, here’s the tricky part: how to break this sequence?

At what point in this sequence can you break free? How can you avoid falling down the slippery slope?

Notice step two: the moment you have attachment—That Lexus is essential for my well-being—can you avoid having Kama? Kama—desire—is inevitable.

And when you have Kama—desire—can you avoid feeling angry when you can’t fulfill your desire? You can’t avoid it, it’s inevitable.

And when you have anger, can you avoid this delusion, obsession? Anger is already distorting your thinking. And you can see these are stages of distortion in your thinking. One sweeps you along. That’s why they call it slippery slope.

One level of distortion sweeps you along into the next one. So anger sweeps you along into obsession. Obsession, Samoha, sweeps you along into Smriti Vibrama—having your values overcome.

Smriti Vibrama sweeps you along into Buddhi Nasha—employing your Buddhi in an Adharmic activity.

There’s an inevitability. And you are helplessly swept along from one to another. How can you break out of that? Once you’ve hit attachment, Sangha, you’re swept away.

So then, what is the solution? Then you look at the first one—Dhyayata Vishayan. If you could avoid seeing the Lexus commercial, then you wouldn’t have a problem. That’s going back and living in the cave and the hypocrisy associated with withdrawing from the world.

You still have the desires in your heart, but you artificially withdraw from the world. You go and live in an ashram in Rishikesh, or a cave in the Himalayas. This is a kind of hypocrisy.

So there’s no solution in avoiding in step one, to avoid being exposed to commercials. You can stop watching TV, I suppose—which is not a bad idea—but it’s not going to solve the problem.

The problem is Sangha—attachment. And that is where the problem can be addressed. Once you have attachment, you can be swept along that slippery slope and be helplessly drawn from one stage of distorted thinking to another stage of distorted thinking.

How can you break free of that? It is by addressing the problem of Sangha—attachment.

We’re actually not going to have time for one more verse. So let me just give you a sneak preview, as it were, of our next class.

How do you avoid that attachment? And that attachment you avoid—and from all of our prior studies here, you’ve come to understand—that you avoid getting attached to the Lexus , for example, by knowing that the Lexus is not essential for your well-being.

That the true source of peace and contentment comes from within—that inner divinity, the truth of who you are, Atma, Sat Chit Ananda—and that is with you regardless if you have a Lexus or not. If you have ten Lexus, or if you don’t have any car at all, you realize that the true source of contentment and peace lies within you. It’s that inner divinity. That recognition is the solution to the problem of attachment.

We’ll see that in our next class.

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ असतो मा सद्गमय ।

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय ।

मृत्योर्मा अमृतं गमय ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Asato Maa Sad-Gamaya |

Tamaso Maa Jyotir-Gamaya |

Mrtyor-Maa Amrtam Gamaya |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om, (O Lord) From (the Phenomenal World of) Unreality, make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the Reality (of Eternal Self),

6: From the Darkness (of Ignorance), make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the Light (of Spiritual Knowledge),

7: From (the World of) Mortality (of Material Attachment), make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the World of Immortality (of Self-Realization),

8: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om, Tat Sat. Thank you.