Gita Class 019, Ch. 2 Verse 55-58

May 15, 2021

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?si=SNRYot5IyPHz22oO&v=l0VufO6KL6k&feature=youtu.be

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

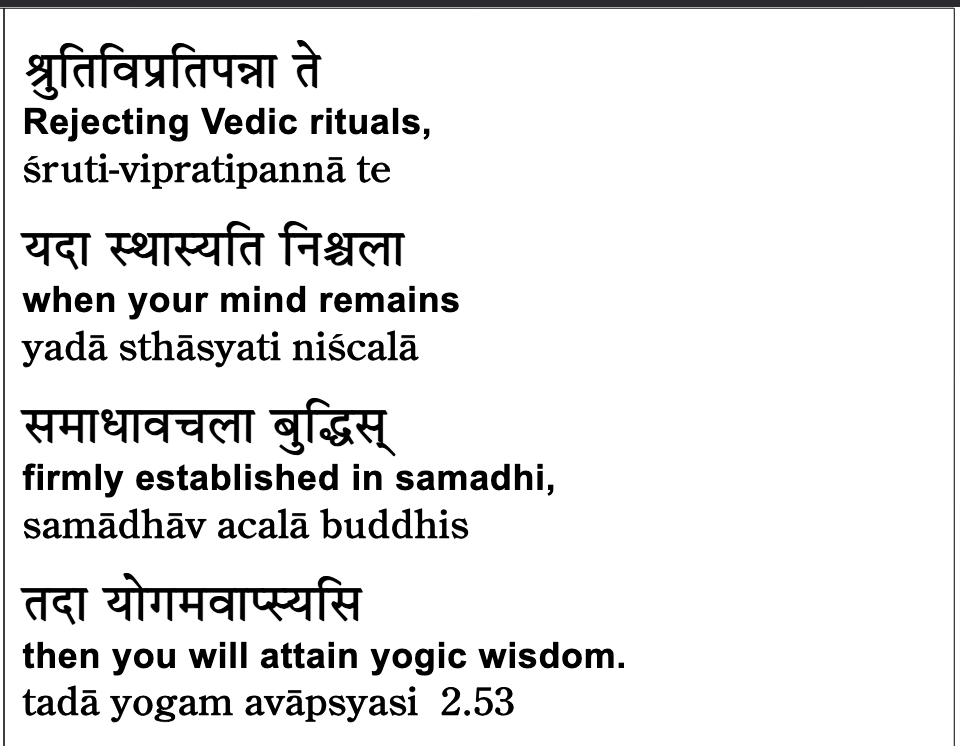

Good. Welcome to the webcast of my weekly class on the Bhagavad Gītā. We continue our study in chapter 2. It looks fine. And we’ll begin some brief recitation with verse 53. And please glance at the translation as I’m chanting and then repeat after me.

Stop there. Back up and pick up the thread.

We are beginning this new section of chapter 2. Chapter 2, you remember—back up more, there you go—chapter 2 is unique, I think, among the chapters of the Bhagavad Gītā, in that it contains several different topics, several different subject matters.

The subject matter that begins, actually with the next verse, is called the Sthita-prajña-lakṣaṇa. Lakṣaṇa—definition, description—of the sthita-prajña, one whose prajñā, wisdom, is sthita—firm.

And all of this whole topic is precipitated by Sri Krishna’s description here in verse 53. We’ve seen these verses already. In verse 53, Sri Krishna describes the enlightened person in the third line: samādhau acalā buddhiḥ. Samādhau—in samādhi. Acalā—unwavering. Buddhiḥ—mind or intellect. One whose mind or intellect is unwaveringly established in samādhi.

Of course, buddhiḥ can not only mean mind, but it can also mean wisdom—which is going to turn out to be a better translation here. But Arjuna apparently misunderstood. Arjuna didn’t understand it as being one whose wisdom is firm. Arjuna apparently misunderstood it as one whose buddhiḥ—mind or intellect—is acalā—unwavering, unmoving, stopped—being samādhau, in a state of samādhi.

So in Arjuna’s mind, he is thinking that when you get enlightened, your mind gets absorbed in samādhi, absorbed in Brahman, and you stop thinking. This is what Arjuna is considering. And he is confused: how can that be—that when you get enlightened, your mind stops thinking?

But with that misunderstanding—oops—with that misunderstanding, Arjuna asks this next question, which we’ve also seen. He says: kā bhāṣā, what is the description sthita-prajñasya—of one whose wisdom is firm, one who is samādhi-sthasya—established in samādhi.

And here it becomes very clear where Arjuna asks: kim, how—sthita-dhīḥ, the one whose mind, dhīḥ, is sthita—firm—for that person, kim prabhāṣeta, how could they even speak? Being absorbed in samādhi, how could they speak? Kim āsīta, how would they sit? And kim vrajeta, how would they move about?

So Arjuna has this misunderstanding, apparently, that when you get enlightened, your mind gets absorbed in samādhi, in Brahman, and your mind ceases to function in a conventional manner. And in reply to that…

And we introduced in the last class, we just began this next verse, 55. And I said in our last class, that what distinguishes—the transformation that takes place—is not a transformation of the enlightened person’s behavior, but rather of the enlightened person’s attitude, thinking, and in particular, motivation. What motivates the activities of the enlightened person? We’ll see all of that in this next verse, and the sequence of verses that follows.

Let’s chant this:

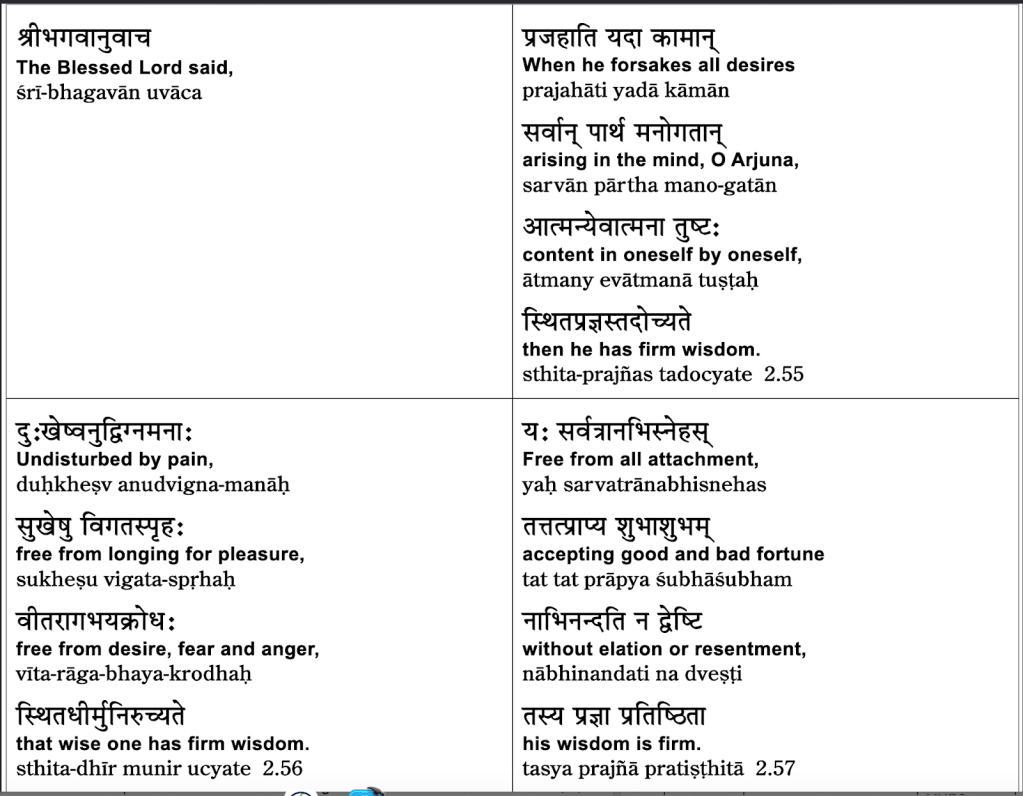

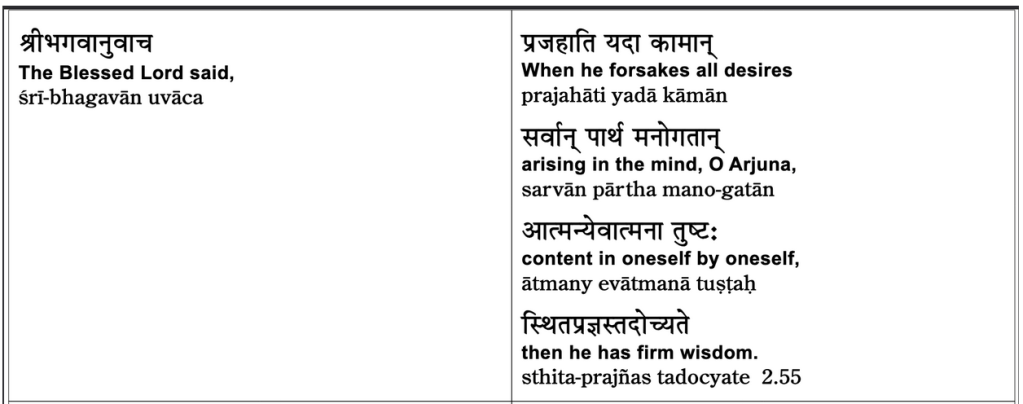

Śrī Bhagavān—the blessed Lord—uvāca, he said in response to Arjuna’s question. And for our Sanskrit students, you see: yadā—when, in the first line, and in the middle of the last line—sthita-prajñas tadā ucyate. Tadā ucyate—so yadā, when, tadā, then.

Yadā—when. We have to combine these words all scattered. Yadā—when. When the person, when—prajñaḥ tadā—when that enlightened person. Prajñaḥ tadā—renounces, abandons, casts off, removes—any of those meanings. When the enlightened person, prajñaḥ tadā, gives up kāmān—desires. Sarvān—all. Sarvān kāmān—all desires. Manogatān—which are in the mind, which are born in the mind. When the enlightened person gives up all desires.

I was reading the Madhusudhana commentary before he makes a nice observation he says if desire was the natural state of atma the true self if desires were natural to atma you’d never be able to get rid of them so he was commenting on his word manoghatan desire belongs not to atma your true self remember atma not as a concept atma as the conscious being which is your essence and consciousness means that by which you’re you know what’s happening right now so we’re not talking about some abstract entity called atma we’re talking about you in a very fundamental sense so that conscious entity which is your your essence is does not possess desire desires belong to the mind manogatan and since they belong to the mind we know that our mind is subject to change so desires that arise in the mind those desires can be removed from the mind of course

Contentment is the absence of desire—we all seek contentment. So we seek the absence of these desires. But the crucial thing here is: how does one get rid of desires? Just a side comment here: there are so many spiritual teachers and spiritual books that say, “You should give up all your desires.” And they say that again and again and again. And of course, it’s a well-founded statement. You won’t be content, in that perfect peace, until and unless you get rid of all your desires. But very frequently, they fail to answer the question: how?

Sri Krishna says very clearly here: you get rid of all those desires by becoming—in the third line end—tuṣṭaḥ. By becoming satisfied, by becoming content. Ātmani—in oneself. Eva—alone. You have to break the words apart: ātmani eva ātmanā tuṣṭaḥ.

We had that really nice discussion at the end of the prior class if you missed that class please go back and and watch that class at the end we discussed how the the irony in fact i may not have brought this point out the irony of life is every day we seek peace and content we see contentment let me just use that very simple expression we see contentment and we engage ourselves in all kinds of extrovert activities seeking contentment and the irony of course is the ultimate source of that contentment is within. I’m smiling because i’m so amused that everyone says the true source of contentment lies within well how many of those people actually seek it within they’re so busy seeking it everywhere else where it’s not that’s the irony of life you can spend a lifetime seeking contentment in all the wrong places failing to seek that contentment within yourself so here the one who is the enlightened person shri krishna describes is one who is tuṣṭaḥ, content content how atmana as one’s own essential nature as yourself you are content and content in what Ātmani eva—in the self alone. when we say atma satchit ananda that word ananda as as we’ve discussed at some length doesn’t mean an experience of bliss. ananda as as we’ve discussed at some length doesn’t mean an experience of bliss because experiences come and go on under is your true nature it doesn’t come and go so ananda refers to your true essential nature as being the ultimate source of contentment so yada when tada then that person is called When prajahāti—when one casts off sarvān kāmān, all desires which are manogatān, which arise in the mind—when all those desires are removed by the mind, how? Tuṣṭaḥ—by one who is content. Ātmani eva—in one’s own. Ātmanā—as one’s true self. Tadā—in the middle of the last line, tadā—then. So yadā—when all desires are cast off, tadā—then ucyate. Then that person is called sthita-prajñaḥ—one whose prajñā, wisdom, is sthita—firm.

Notice that it’s your wisdom that is unwavering, not your mind. This is Arjuna’s confusion. He thinks that the mind becomes fixed and unmoving. It’s not your mind that becomes fixed and unmoving—it’s your wisdom. You become firmly established in wisdom. It’s the nature of the mind to be active. How unreasonable it would be to expect that our minds—Bhagavān created our minds to be very agile and always active—how unreasonable to expect that enlightenment should result in a cessation of the God-given natural activities of the mind. This is the confusion that Sri Krishna is answering here.

And before we move on, just to pick up my statement in my introduction, I said that what distinguishes the enlightened person is not the person’s behavior, but the person’s attitude—in particular the person’s attitude towards action.

Now generally, actions are motivated—we’ve discussed this at length. Conventional actions are motivated by desire, by rāga and dveṣa. The enlightened person acts like a normal person, but not motivated by rāga and dveṣa. Not motivated by rāga and dveṣa, because ātmani eva tuṣṭaḥ—they’re already fulfilled and content. They have no desires. They have no rāga-dveṣa. Then why do they act?

There is the old story, which I think conveys the point very nicely, where the old master tells his young student: “Before I was enlightened, I used to chop wood and carry water to take care of the āśram.” And the master goes on to say: “Now that I’m enlightened, I chop wood and carry water.” And you’ve heard this story, of course.

The message, I’m sure you understand. The message is that previously the master chopped wood and carried water driven by desire. You chop wood—you desire for warmth, you need wood for cooking, and water also. So the chopping wood and carrying water was previously driven by desire, rāga and dveṣa. Now that he is enlightened, the master continues to chop wood and carry water, but no longer motivated by desire—motivated by a sense that this needs to be done. If something needs to be done, you don’t have to be driven by desire to do it. You can just be driven by that sense of dharma. Water needs to be brought. Wood needs to be chopped. Yes. Very simple.

You know, just like when you’re hungry, it’s natural to eat. When you’re not hungry—that is an interesting side point. When you’re not hungry, how many people eat when they’re not hungry? Lots. Lack of contentment. If you’re not hungry, just an insight: if you’re not hungry but you feel the absence of contentment, even though you’re not hungry, you may go and eat something. Not because you’re hungry, but because you’re seeking contentment. This is the problem of rāga-dveṣa.

So an enlightened person is one who eats when they’re hungry and doesn’t eat when they’re not hungry. Sleeps when they’re tired and doesn’t sleep at other times.

The enlightened—oh, interesting. Pūjya Swami Dayananda, my guru, once made this remarkable statement about an enlightened person. Listen carefully. He said: “An enlightened person is a normal person—the only normal person.” You get the point. And that is from Pūjya Swamiji’s perspective: conventional behavior is not quite normal.Not quite normal, because why? It’s not normal to eat when you’re not hungry. But driven by raga and dvesha, people who aren’t hungry eat. And in Pujaswami’s view, that’s not normal.So an enlightened person is a normal person, the only normal person, meaning a person whose behavior is not distorted and compelled by raga and dvesha.

You become—the enlightened person becomes—tuṣṭaḥ, content. Ātmani eva—in the self alone. Means not contented through external pleasures. And how does he do that? Ātmanā—by oneself, or better yet, as oneself. As oneself, you become content as one’s true self, ātman. As one’s true self, as sat-cit-ānanda ātman, you become tuṣṭaḥ—content—ātmani eva—in oneself alone.

Okay, nice. Let’s continue.

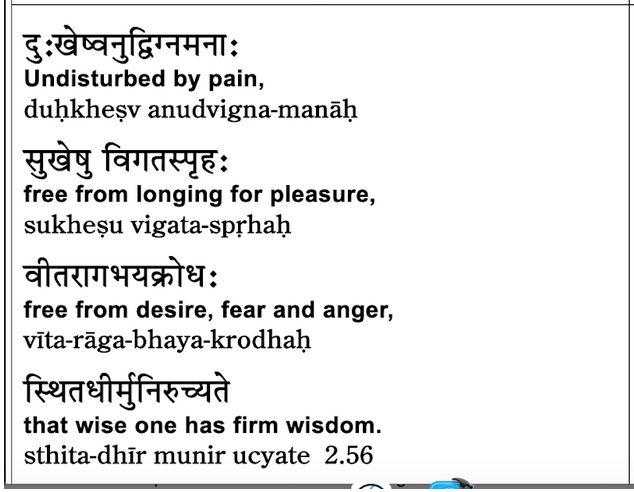

Sthita dhir is the same as stitha pragnyaha, one whose dhihi, dhihi means buddhi, intellect, or better yet wisdom. One whose dhihi, one whose wisdom is stitta firm, muni hi, that and munihi is used in a sense of an enlightened person. It has many other meanings, so that muni hi, that enlightened person, which chate is called, muni hi, which chate, that enlightened person is called stita dhihi, one of firm wisdom.

And how is that person described, go back to the first line? Dukeshshu in the presence of pain, excuse me, dukha here meaning pain, dukeshu in the presence of pain, unudvigna manas, one whose manas mind is unudvigna undisturbed. One whose mind is undisturbed in the presence of pain.

And here we have to, I think we’ve discussed the difference between pain and suffering. It’s important to return to that point once again.

Pain is a physical sensation. Suffering is your negative response to that physical sensation.

So physical sensation is just, you know, when you pinch, pinch yourself, you feel a little bit of pain. But suffering is a negative response to that pain. If someone pinches you, you get angry. Why did you pinch me? That negative response is suffering, or sadly in the case of chronic pain.

When people feel, why does this pain continue? I won’t be okay until this pain goes away. That’s suffering.

Pain is just a sensation. Sensation like sound reaching your ears. Sensation like images reaching your eyes. Pain is a sensation born of your skin and other organs, nerve system organs. Nerve system organs. I don’t make any sense. But I think you understand what I mean.

So pain is a simple sensation. And you can look at something without being disturbed by it. You can hear something without being disturbed by it. Then you should be able to experience a sensation like pain without being disturbed by it.

When you’re enlightened, you can. This is the distinction between pain and suffering.

The person is also a sukeshu. So first one, duke-shu in a presence of pain. And secondly, sukeshu in a presence of pleasure. Vigata, spraha. The person is free from spraha, longing, or attachment.

Many, many commentaries make this observation. Very kind of sarcastic observation. They observe that even in pleasure, they’re suffering. You wonder, how can there be suffering in pleasure?

And the point that this usually is, and you find this in commentaries, where the commentator will say, even while you’re enjoying something, you know that the enjoyment will come to an end. And you’re fearing the end of that enjoyment.

So even your enjoyment is painted by suffering, suffering in the form of the fear and anticipation that the enjoyment will come to an end. An interesting observation.

But here, the enlightened person suke-shu, even in the presence of pleasure, they’re not expecting or depending on the continuation of the pleasure. Just as pain comes and goes, so too, pleasure comes and goes.

They’re sensations, they come and go, and your true self-consciousness is utterly unaffected by these sensations. Sensations arise in your mind, sensations pass away in your mind. Whatever sensations arise and fade away from your mind, all those sensations are revealed by consciousness, illumined by consciousness, and just like the sunlight is unaffected by what illumined, whatever it illumines, in the same way, your consciousness is utterly unaffected by all the transient sensations that arise and fade away from your mind.

Then, the enlightened person, the stita-dihi-munihi, the enlightened sage is described in the third line as being Vita-ra-ga-bhaya-krodah-vita without.

Vita-ra-gaha without raga-desire. Vita-bhaya without fear. Vita-krodah without anger. So, raga-desire, we’ve just got to get some length, but let’s look at these two other words. Without fear and without anger, how is it that the enlightened person is free from fear and anger?

Atmani-eva-tushdaha in the prior verse. Being content in oneself. Being content in such a sat-cit-nanda-atma, the true self, the true self which is limitless, full and complete, therefore your contentment is not a little bit of contentment. The contentment you find in your true self, the contentment you find within is vast, complete, perfect, and unbroken, uninterrupted, perfect, complete, uninterrupted contentment.

Uninterrupted means it doesn’t come and go. If you find in yourself this perfect peace and contentment which doesn’t come and go, tell me what could possibly threaten you? What could rob you of that contentment? Nothing.

If it is uninterruptable, I’m not sure if that’s a word. If it’s uninterruptable, it can’t be taken from you. It’s your true self. No one can rob you of your true self.

Having discovered that true self as being uninterruptable contentment, nothing can threaten you. You’ll never experience fear. We experience fear when we’re threatened. But that leads to another funny misconception.

And that is, an enlightened person experiences no fear. Does it mean that if you point a gun at an enlightened person, the enlightened person will just stand there and allow you to kill them? The enlightened person will run away, but will run away not driven by fear. Will run away based on what is normal and natural.

It’s natural to run away from something that threatens your life. Notice a difference. An unenlightened person will run from a threat due to fear. An enlightened person will similarly run from the same threat, but not driven by fear.

They will run because it’s normal. It’s Dharma. Dharma to protect your body after all. To protect your health, to protect your life is Dharma. So based on Dharma, based on it being normal and natural, the enlightened person will run from a threat.

Also, Vita Raga, free from desires, Vita Baya, free from fear, we just discussed. And finally, Vita Kroda, free from anger.

When we are threatened, we usually have one of two responses, a fight or flight. Fear is the flight response, and anger is the fight response. When there is a threat, there is either Baya or Kroda, fear or anger, flight or fight. This is our normal response.

So Kroda, anger, you get angry when someone or something threatens you, you want to resist it. And anger, I suppose, in terms of our evolution, anger gets our sympathetic nervous system fired up, so we are ready to fight against the threat. When anger is part of that, anger is preparing you to fight.

But if you are not threatened, why will you get angry? This is a really important point. You get angry when you feel personally threatened.

Consider, look at this. Suppose you are taking care of a toddler, a three-year-old, four-year-old. And the three-year-old gets, has a temper tantrum, and you are the caregiver, and the three-year-old looks at you in anger and says, you stupid.

The three-year-old is putting you down, is insulting you. Do you get angry at the three-year-old? I hope not. Some people do. But if you are a stable mature person, you won’t get insulted by the three-year-old.

Why? Why should you be threatened by the three-year-old? Look at this. If you can be okay when a three-year-old calls you stupid insults you, then why not when a 33-year-old insults you?

If you have discovered that perfect uninterruptible contentment within you, then why should the 33-year-olds insult you any more than the three-year-olds insult?

This is what it means to be enlightened. Nothing can threaten you.

Pujya swamiji used to use an expression. When you are bigger than a situation, bigger not in a physical sense, bigger maybe in an emotional sense. When you are bigger than a situation, the situation cannot threaten you.

And how big is such a rana-dha-atma? Boundaryless, limitless. When you recognize your own boundaryless, limitless nature, you become so big inside, so to speak, that nothing at all can possibly threaten you.

Stitth-dihi-munihi-uchihe, such an enlightened person is called stitth-dihi, same as stitth-apragnya, one whose wisdom is firm.

Then,

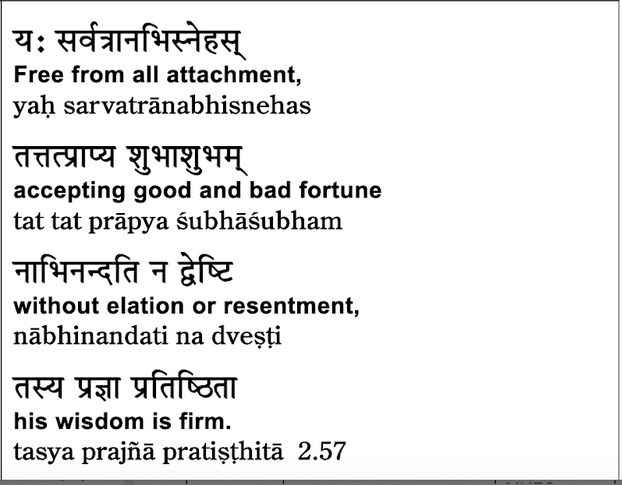

Yaha, one who, one who Sarvatra in every possible situation, one who is an abi-snehah.

Snehah is an interesting word. I find it interesting. Snehah, Hindi may, sneh. And in Hindi it has kind of a nice meaning. Yaha, sneh means love, affection, sneh. Usko, snehah. If you have a, you have affection for someone or another.

But the Sanskrit meaning is so different because snehah comes from a root, sneh, which is to stick. In fact, one of the meanings of snehah in Sanskrit is sticky. So, and it’s used in Sanskrit in a, in a sense of attachment to have snehah for someone is to be attached to someone.

Now, Hindi meaning is very nice. The Sanskrit meaning is pointing out something quite different. Nehah here means attachment. The sticky love, clinging love. And clinging love is not love at all.

Love means I love you in condition, love means unconditional regard and affection and concern. But this clinging love is more like I need you. Attachment or clinging, clinging love. It’s not love at all. It’s emotional dependence. If you cling to someone, doesn’t mean you love them. Means you’re dependent on them. Emotionally dependent on them. That’s not love at all.

So, here, snehah or abhisnehah, same meaning, abhisnehah and snehah, both have the same meaning of emotional dependence or attachment. And a person who is yaha, one who is sarvatra, in all situations with regard to all people and all situations, unabhisnehah, person who is utterly free from attachment.

And again, free from attachment means free from emotional dependence. And to be honest, only one who is totally free from snehah, from this emotional dependence, that person is capable of unconditional love. An conditional love always has some degree of emotional dependence. Unconditional love is love that is absolutely free from unconditional, from absolutely free from emotional dependence. It is a rare thing.

Anyway, I don’t want to get off too much on that topic. It’s a big topic, an important topic. We’ll see it perhaps in another context.

So first, yaha, that enlightened person is sarvatra for all people.The person is un, abhi, snehah, totally free from attachment, totally free from emotional dependence.

And further, tat, tat, prapya, when that person receives tatt, tatt, propya, having, having received tatt, tatt, whatever thing, tatt, tatt means whatever thing. And whatever thing which is shubha, auspicious or asubha, inauspicious. And in context, you can say shubha is something that’s pleasant or desirable.

Conventionally, when you get something that’s pleasant, you smile. And when you get something that’s asubha, unpleasant, you frown. Or better, better yet, you complain. Oh, why is that happening to me?

So that’s conventional behavior when something good happens, you’re delighted. And when something bad happens, you resist. And when something bad happens, you resent it and complain about it.

But for the enlightened person, tatt, tatt, propya, if they receive something which is shubha, pleasant, nah, abhinandati. The person doesn’t abhinandati, rejoice. The person doesn’t get puffed up with the pleasure, doesn’t become elated. It is a good translation.

And prapya, asubha, when the person experiences something which is unpleasant, unwanted, undesired, nahdhuesti, the person doesn’t hate it. And hate is literally the right is what it means. But the person doesn’t resent it or despise it.

So often when something negative happens to us, there’s a sense of resentment. Why did this have to happen to me? I wish this didn’t happen to me.

Things happen. Good things happen to you. And not so good things happen to you. You all understand the doctrine of karma. Because you’re born with both good and bad karmas, you are, it is inevitable. You will receive in this life many good things that you don’t deserve based on your conduct in this life. And you will receive many undesirable things that you don’t deserve based on this conduct in this life. That’s the doctrine of karma.

Most people, when something good happens, they rejoice. And when something terrible happens, they get depressed. And they resent whatever happens.

The enlightened person can accept, can gracefully accept whatever happens in life as being the natural unfoldment of karma. If something good happens, it’s the natural unfoldment of karma. If something terrible happens, it’s the natural unfoldment of karma.

The enlightened person can accept all that gracefully because he or she knows the true source of contentment within. They know that they are not, they are not, when something good happens, it doesn’t add anything to them. And when something terrible happens, it doesn’t take anything away from them.

Again, atma is already full and complete. Atmas, your true nature, you can’t add anything, you can’t take anything away. It is full and complete and unchanging.

The enlightened person is one who knows this. Therefore, when something good happens, nah, abhinundati, that person doesn’t rejoice. And when something bad happens, nah dwesthi, the person doesn’t resentment.

Tasiya, tasya, for such an enlightened person, the pragnya, that person’s wisdom, understanding, pratishtita is firm.

And again, notice the language. Sri Krishna doesn’t say that the mind is firm. Mind is mind. Mind is always moving. What is firm and unchanging is the person’s wisdom, understanding.

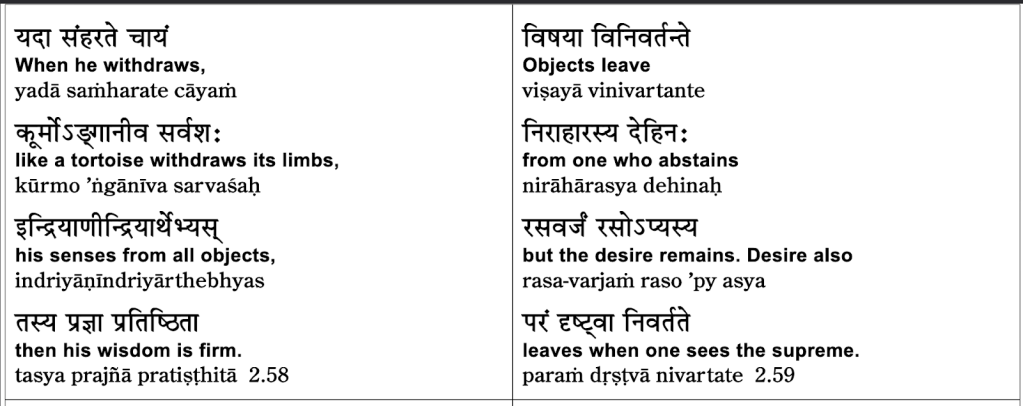

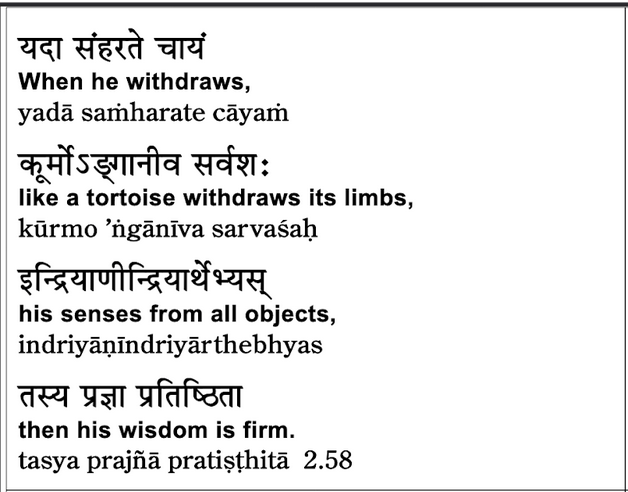

So here, Sri Krishna gives a metaphor. In Sanskrit, a metaphor is called dristanta. Dristanta is something that represents something else.

Here in the second line, the dristanta is a kurmo. Many of you know kurma is a turtle, a tortoise. And you know that a tortoise does what? Angani, iva, iva. Just iva, just like kurama, a tortoise. What does a tortoise do in the first line?

Samharate, the tortoise withdraws. What draws what? In the back in the second line, Angani, its limbs. The tortoise withdraws its limbs.

You know this very well. When a tortoise is frightened, the four legs are drawn into the shell. The head is drawn inside the shell. The tail is drawn inside the shell. And drawn away Sarvashah in all directions, from all directions, the tortoise when threatened withdraws all of its limbs from all directions.

And this is the dristanta. So the dristanta in the first line, you have to break the words apart. It is yaha samharate cya ayam. Cya and ayam kurmaha. This tortoise, some tortoise, samharate it withdraws Angani, its limbs Sarvashah, from all directions, iva, just like that tortoise, that withdraws its limbs in all directions.

In the same way now comes the darshtanta. Dhrishtanta is a metaphor. Darshtanta is what the metaphor represents. And that comes in the third line.

So the stithapragna, the one whose wisdom is firm, does what and picking up the samhatate, and the first line withdraws, withdraws what? Indriyani senses.

So the senses are withdrawn from what? Indriyartebhyaha from sense objects.

Let me paraphrase this. Just like a tortoise withdraws its limbs in the same way a wise person withdraws the sense organs from sense objects.

Sense organs are sight,hearing,taste, smell and touch, and the mind is often considered a sixth organ, as it were. So it’s a good metaphor because the tortoise has four legs and a tail, representing your five senses, and the tortoise also has a head representing your mind.

So the tortoise withdraws all six of these into the shell, in the same way the enlightened person withdraws as it were.Notice that word iva, applies in both in both the Dhristanta and the Darshtanta. The enlightened person, as though withdraws the senses from sense objects.Now the idea is that sense objects are a source of pleasure or pain, and the enlightened person withdraws. Now be very clear. This withdrawal isn’t like closing your eyes. If there’s something you don’t want to see, you close your eyes. Well that’s one kind of sense, one kind of withdrawal. That’s not the withdrawal that’s intended here though. The enlightened person, let’s make this clear, the withdrawal of the enlightened person. Is the absence of dependence on external objects. Conventionally people depend on external people and objects for their happiness and contentment. The enlightened person is free from that dependence on external objects and people for their happiness and contentment.So this withdrawal is not like, in fact it’s quite different. In one way it’s similar to a turtle in the sense that there is withdrawal. But what’s different is that the turtle’s withdrawal is shutting themselves up inside the shell. The enlightened person doesn’t have to shut themselves up inside any kind of shell. As we said in a prior verse, there’s nothing to be afraid of, nothing can threaten the enlightened person. So that withdrawal represents the absence of dependence.

Now you might think that, well therefore the tortoise is not a very good metaphor. Well there’s another part of the metaphor. The other part of the metaphor is this, when a turtle is threatened, it doesn’t run away. It doesn’t need to run away. It just withdraws its limbs and it’s perfectly safe and content there itself without running away.And this is perhaps what the metaphor really wants to convey that the enlightened person, when threatened, doesn’t need to run away. Inside the shell, the tortoise is perfectly safe and content. Inside oneself, the enlightened person is perfectly safe and content. That’s the sense of the metaphor. So it’s not that the enlightened person is somehow closing their eyes to the world around them. But rather the withdrawal indicates non-dependence on any external thing for happiness and contentment. And also not needing to run away. The tortoise doesn’t need to run away. Content and safe in the shell, in the same way the enlightened person doesn’t need to run away from anything.

Tassya Pragya Pratishtata. Tassya Pragya for that enlightened person, the enlightened person’s Pragya Wisdom, Pratishtata is firm. As it was said in the previous verse.

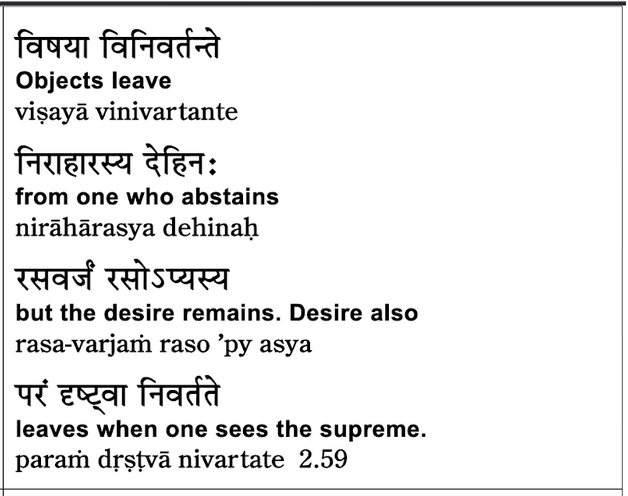

We’ll see one more verse here. Finishes this part of the topic.

This verse will take quite a bit of explanation. So I think it would be a mistake to get started with it here at the end of the class. So we will see this verse when we resume next week.

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ असतो मा सद्गमय ।

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय ।

मृत्योर्मा अमृतं गमय ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Asato Maa Sad-Gamaya |

Tamaso Maa Jyotir-Gamaya |

Mrtyor-Maa Amrtam Gamaya |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om, (O Lord) From (the Phenomenal World of) Unreality, make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the Reality (of Eternal Self),

6: From the Darkness (of Ignorance), make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the Light (of Spiritual Knowledge),

7: From (the World of) Mortality (of Material Attachment), make me go (i.e. Lead me) towards the World of Immortality (of Self-Realization),

8: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om, Tat Sat. Thank you.