Gita Class 018, Ch. 2 Verse 51-55

May 8, 2021

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mok7m5Uj0-0&list=PLeP4eulMEXiOC8DjxjFc2Vt1yEtD8IAbl&index=18

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

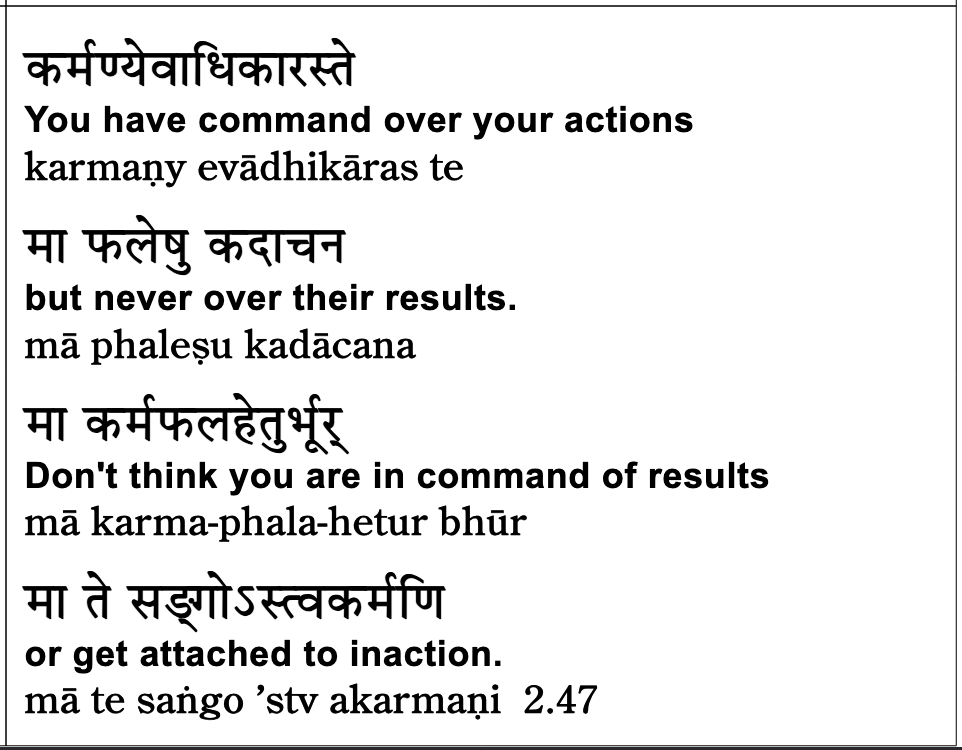

Good. Welcome back. We continue our study of the Bhagavad Gita in chapter two. We’ll begin with some recitation beginning with verse 47. Please glance at the meaning and then repeat after me.

Very good. Excuse me.

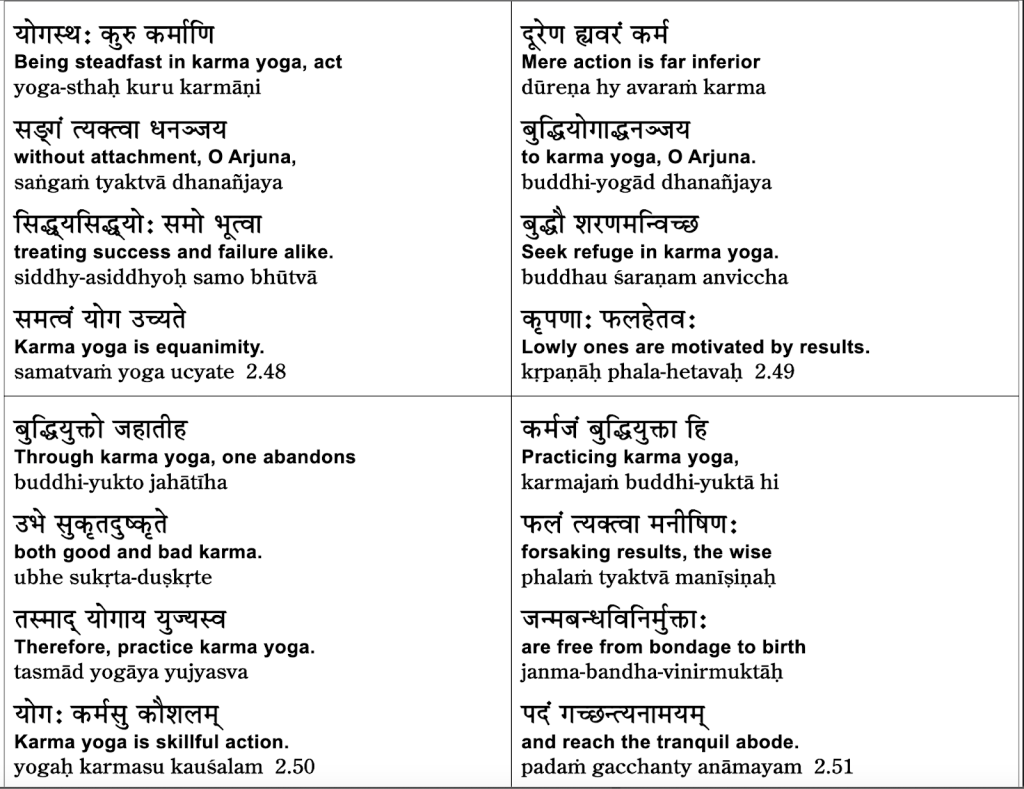

Okay, we’ll continue today from verse 51. Yes, yes, good. And just to introduce our class today, we are in the midst of this topic of karma yoga. Even though chapter three is titled Karma Yoga, the topic is so important it starts in chapter two. We’ll see a little bit more of it today. And then in chapter three, the entire chapter is karma yoga. Chapters four and five are also concerned with karma yoga. And then in chapter 18, when Sri Krishna summarizes the teachings, the topic comes back once again.

So it’s fair to say, if there’s any topic in the Bhagavad Gita that really stands out as being a predominant topic, certainly it is karma yoga. And as we discussed in the last couple of classes, karma yoga is not what you do. It’s the attitude with which you do something.

And just to summarize that one last time here, one last time because we’ll finish this topic of karma yoga in chapter two today. We’ve said that karma yoga is a set of attitudes in which you shift your motivation for doing what you do. Usually we are motivated by Raga and Dwaisha. Raga, a compulsion to get what you want. Dwaisha, compulsion to avoid what you don’t want. Karma yoga replaces that motivation with the seeking of spiritual growth.

When we understand that our ultimate goal in life is not the momentary pleasures we pick up in our day-to-day activities, but when we understand clearly that the ultimate goal for us is moksha, liberation, gaining perfect peace and contentment through a life of spiritual growth—with that shift of understanding, our motivation also shifts. So that instead of our actions being driven by Raga and Dwaisha, our actions are driven by being on this path of spiritual growth. Our actions are driven towards moksha. Away from Dharma, Artha, Kama—to recall our prior discussions about the four Purusharthas. So we shift from Dharma, Artha, Kama, and we shift to moksha.

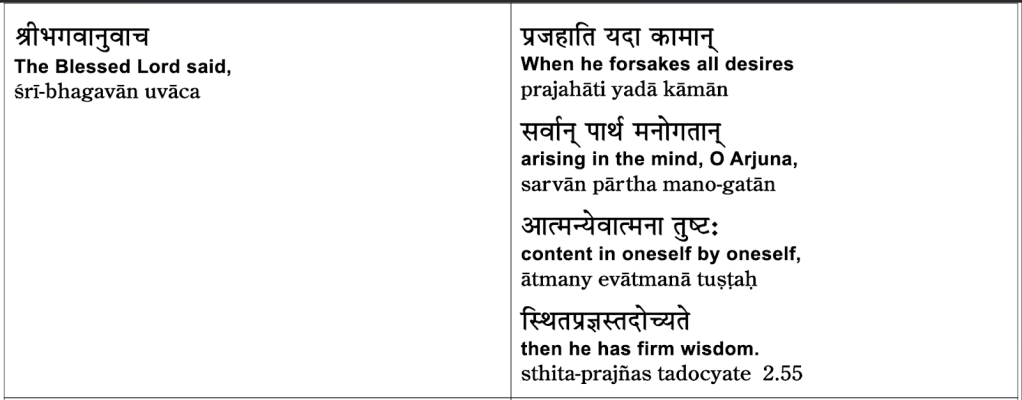

Okay. With that introduction we continue with verse 51.

In the second line, Manishinaha—people. What kind of people? In the first line, Buddha Yupdaha—people who are endowed with this buddhi, this attitude of karma yoga, people who are engaged in the practice of karma yoga. He indeed. These people who have shifted their focus in life from these transient pleasures, they’ve shifted towards gaining moksha through a life of spiritual growth.

With that shift of attitude, Tyaqtwa in the second line, having given up Karma-jambudhi, Phalam—we have to connect those two words—having given up the phala, the fruits, which are karma-jambudhi, born of their actions, having given up the fruits of their actions.

And giving up the fruits of the actions means you are motivated not by the little pleasures you pick up throughout the day, but you’re motivated instead to gain moksha. If your ultimate motivation is moksha, your motivation is no longer focused on those little pleasures throughout the day.

Now just an observation here. Notice Sri Krishna says Phalam-tyaqtwa, giving up the fruits of your actions. So often people describe karma yoga as giving up the desire. Giving up fruits is what Sri Krishna says; giving up desires is what many people misinterpret this as. Notice he says Phalam-tyaqtwa, giving up the fruits of your actions. He doesn’t say Kamam-tyaqtwa, giving up desires. And we had that discussion in the last class.

So many people misinterpret karma yoga as to act without desire. Sri Krishna says to act without desiring the results, but now that gets generalized into acting without the desire for anything. They’ll call it nish-kama karma. Nish-kama means without desire, to act without desire.

And I gave that silly example in the last class—that is, you can’t give up your desire. The example I gave you, remember, is someone who feels they’re drinking too much tea, and that tea is an impediment somehow to their spiritual growth. They decide to give up drinking tea. They stop drinking tea. They’ve given up the tea. Have they given up the desire? They continue to desire to drink tea. They desire tea, they’re not drinking tea. Please note: you cannot give up desire as a matter of choice. You can’t willfully give up desire, as we discussed in our prior class. You can come out of those desires, you can overcome those desires, but you cannot give up a desire.

Then the problem rests, I think, with this word nish-kama karma, which means literally karma, action, which is nish-kama—completely free from desire. Again, that’s not what Sri Krishna says here. He says to act without desire for the fruits. He doesn’t say to act without desire. For the reason I just said—no ordinary person will act without desire. If you had no desire, you might not get up, get out of bed in the morning.

Desires are normal, and desires, as we said before, aren’t even the problem. The problem is the compulsion of Raga and Dwaisha. But here, to understand this word nish-kama better—in fact, in the next section of chapter two, we’re going to discuss this—nish-kama karma is the action performed by an enlightened person.

An enlightened person is totally fulfilled and content and totally at peace. Therefore, the enlightened person experiences no desire, no sense of want, no sense of inadequacy or limitation. So whatever actions are done by an enlightened person—we’ll discuss this at some length starting with the next class, not today.

So we could say then that the enlightened person is the one who truly performs nish-kama karma, the desireless action. But now, if you think that you can practice nish-kama karma as a sadhana, as a spiritual practice, that’s like saying you’re going to practice being enlightened. If an enlightened person is the one who performs nish-kama karma and you decide that you’re going to perform nish-kama karma as a sadhana, as a spiritual practice, that means you’re practicing being enlightened. How do you practice being enlightened? That’s silly.

The point I’m making is a little bit subtle, but it’s rather important. That’s why I’m dwelling on this just for a moment. Action that is utterly desireless is the action of an enlightened person, which we’ll discuss in the next class. Here, we are not discussing desireless action, nor does Sri Krishna say that you should act without desire. He says you should act phalam tyaktva—giving up the fruits of the actions—which means you’re no longer motivated by the limited pleasures, the momentary pleasures you’re going to get are the goal. You’re motivated instead to get moksha, and your desire for moksha is still a desire.

Please notice, you will have these desires—either for limited pleasures or for moksha—until the day you’re enlightened. By the way, several people have commented: isn’t the desire for moksha still a desire? Absolutely. But it’s a unique desire. If you desire anything else, those other desires only lead to further desires, more and more desires. That desire for moksha is the only desire that can ultimately come to an end. Any other desire will lead to further desires. The desire for moksha can ultimately lead to liberation, to moksha, in which case the desires come to an end.

So the desire for moksha is a desire, but it’s a unique desire, unlike any other kind of desire. So before we move on now: nish-kama karma, properly understood, desireless action, is the natural state of an enlightened person. For the karma yogi—the karma yogi is not expected to be desireless. In fact, the karma yogi at least has a desire for moksha. And here, Sri Krishna says very clearly that the karma yogi doesn’t give up desire. The karma yogi gives up phalam, karma-jam phalam—the fruits of one’s actions.

The limited fruits, those momentary pleasures, are not the focus of your life. You’re no longer motivated to seek those momentary pleasures. Your ultimate motivation is to gain moksha. So such people, buddhi yuktaha—such people who are endowed with this buddhi, this attitude of karma yoga—what about them? Jya in the third line, janma bandha vinir muktaha—they become vinir muktaha, completely freed from the bandha, from the bondage that began with this janma, this birth. Or, freed from the bondage of being reborn again and again and again.

And the reason Sri Krishna says this is that karma yoga leads eventually to moksha, to liberation. When you’ve gained moksha, liberation, you’re no longer subject to rebirth. And having gained moksha, padam gachanti. Gachanti—they reach the padam, the state, the goal. The goal which is anamayam, completely free from suffering.

Karma yoga alone will not lead to moksha. Remember, we’ve had discussions long ago that the primary obstacle to liberation is failure to recognize your innate divinity. That inner truth, that inner divinity, is covered by ignorance. When that ignorance is removed, you discover tat tvam asi. You discover you are That. You discover that fullness and completeness, the divinity within. But that knowledge will never take place unless your mind is properly prepared.

And proper preparation of your mind requires overcoming Raga and Dvesha. As long as your mind is dominated by Raga, Dvesha—remember, they’re compulsions—as long as your mind is bossed about. The Raga and Dvesha, I have said before, they’re like bosses. Raga is a boss in your mind telling you, “Do this, do this, do this.” And Dvesha is a boss in your mind telling you, “Avoid this, avoid this.” Your mind is constantly manipulated and compelled by Raga and Dvesha. As long as Raga and Dvesha hold their sway, your mind will never be ready to discover this inner truth we just discussed.

Therefore, karma yoga is essential to overcome Raga and Dvesha, which are perhaps the biggest impediment on the path to spiritual growth.

Okay, enough said.

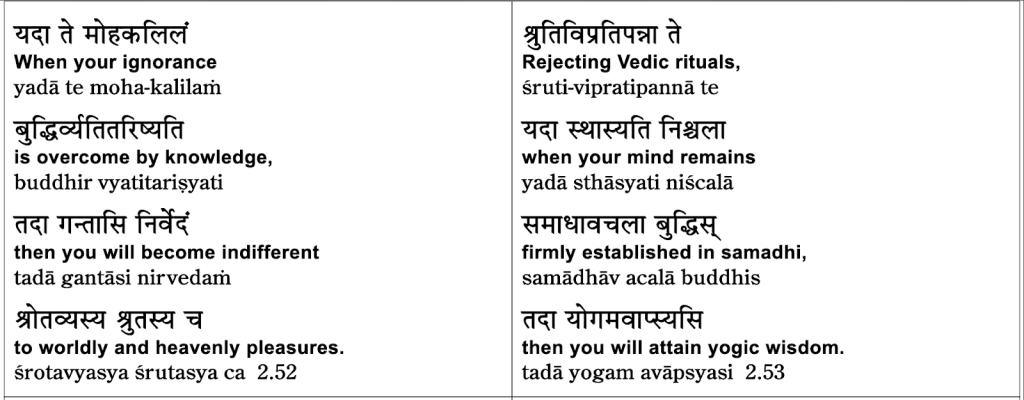

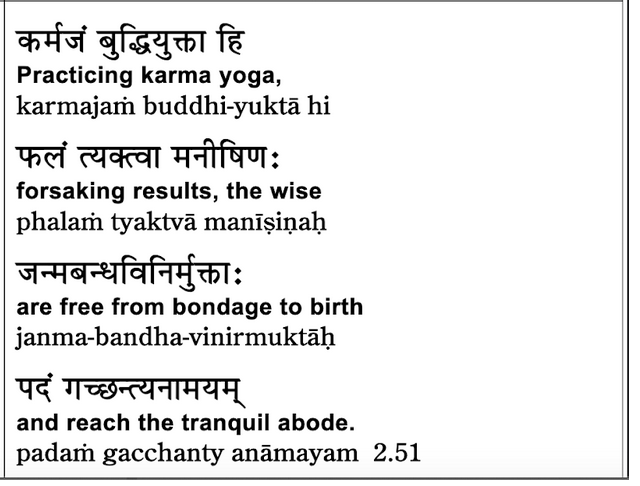

Yada… When? And you see, Tada in the second line—then. These two words go together. Yada, when this happens; Tada, then that will happen.

So when what happens? Yada—when. Te buddhi (connected in the second line), te buddhi—your mind, or your attitude, your mind, we’ll take it first. Yada te buddhi—addresses Arjuna: O Arjuna, when your buddhi, your mind, intellect, intellect—when your mind vyatitarishyati, when your mind will transcend. Literally “cross over,” vyatitarishyati. To cross over means to transcend, to come out of something. To come out of what? Moha kalilam.

Moha means delusion or just simply ignorance. Kalila has several meanings. One meaning is like a covering or an accumulation. So as I just said, that inner truth, your true divine nature, that atma—as sat-chit-ananda, as being consciousness which is limitless, boundaryless, full and complete, all-pervasive. That inner truth is obscured by ignorance, covered by the so-called veil of ignorance.

And here Sri Krishna says to Arjuna: Arjuna, yada, when te buddhi, when your intellect, when your mind vyatitarishyati—overcomes moha kalilam, this veil of ignorance that covers the true self—tada, then gantasi. Then you will reach nirveda. Nirveda means dispassion. In fact, it’s a synonym for vairagya. Vairagya—free from Raga, free from this passion, free from this Raga and Dvesha, free from compulsion. So Arjuna, when your mind has removed this veil of ignorance that covers your true self, then gantasi—you will reach nirveda, this condition of… It’s translated here as “indifference,” and “indifference” may give the wrong sense here. Indifference means, “Oh, I don’t care.” But here it’s a condition in which you find yourself innately full and complete, established in a state of perfection, contentment. And with that state of contentment—contentment is, by definition, the absence of Raga and Dvesha. These are the opposites. On one hand is Raga-Dvesha. On the other hand is contentment. They can’t coexist. The compulsivity of Raga-Dvesha is the enemy of contentment.

But here, Sri Krishna is describing a condition in which Raga and Dvesha have been overcome. Through the practice of karma-yoga and with the help of the teachings of Vedanta, the veil of ignorance covering your true nature is removed. And then, gantasi, you will reach nirveda—a state of indifference, a state of being dispassionate. But a better, more nuanced interpretation would be: a state in which you’re no longer compelled by desires. You’ve broken free from Raga-Dvesha, and you’ll have no more desires.

Yashya—for what is, what is too literally for what is to be heard? That’s a little obscure, but I’m smiling because it makes me think of commercials on television. Commercials on television have a very specific purpose. And what is their purpose? To instill in you a desire for their product. That’s what advertising is all about. So there could be a new product that hasn’t been announced yet, and as soon as the commercial for that product comes on TV, you see that product, and in your mind is instilled a desire for that product.

And here, Sri Krishna says that you will gain nirveda—dispassionate indifference—shrotavyasya for those products which have yet to be announced on TV, yet to be advertised, but they will be advertised. This is in the future sense. Shrutasya—and also for things. There’s a technical interpretation here. Shrutasya could be for what you’ve already heard, but there’s a more technical one.

So things that—the simple meaning here is—you’ll gain dispassion for shrutasya, for things you’ve already heard about, shrotavyasya, and for things that you will hear about. Things that you’ll be dispassionate towards: shrutasya, for all the products you already know about, and shrotavyasya, for the products you have yet to hear about.

But a commentator points out a more sophisticated understanding of shrutasya, because it comes from shruti, being a word for scripture. So here, the more sophisticated interpretation is you’ll gain dispassion shrutasya—for worldly things, and shrutasya—for things described in the scriptures. “Things” meaning going to heaven, getting a better rebirth. So you’ll gain dispassion for all this, having gantāsi nirvedam, having attained the state of perfect contentment.

How do you gain that state of perfect contentment? The practice of karma-yoga prepares you to discover your true inner nature, and you can remove that veil of ignorance. The removal of that veil of ignorance leads to this state of perfect contentment. And that leads us to the last of the series of verses on karma-yoga. So we’ll see that first.

This, as I mentioned, is the last verse in this section on karma-yoga. This section that occurs in chapter 2—and as I said, we’ll return to the topic of karma-yoga in future chapters.

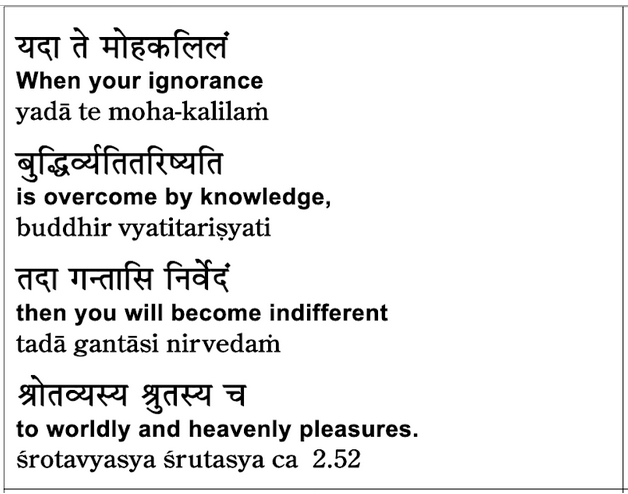

For Sanskrit students, you see once again yadā in the second line and tadā in the fourth line: yadā—when, tadā—then.

So Sri Krishna says to Arjuna, yadā—when. “When”—now we have to connect words that are spread out here. Yadā—when, te in the first line, and buddhi in the third line. Remember that these verses are written in a poetic meter, and the demands of the poetic meter often result in the jumbling of the normal word order. So we have to be ready for that.

Yadā, Arjuna—yadā—when te buddhi. When your mind, when your intellect, when your mind or intellect is what? First line: shruti-vipratipannā. When your mind is vipratipannā—turned away from shruti.

We just saw that word in the prior verse. Shruti—scripture, and in particular, scripturally described goals like getting to heaven or getting a better rebirth through the performance of Vedic rituals. So earlier in the section on karma, before we saw this section on karma-yoga, we had a lengthy discussion about what karma-yoga is not. And in that discussion, Sri Krishna said very clearly: karma-yoga has nothing to do with the performance of Vedic rituals. Vedic rituals—vaidika karma. So Vedic rituals are karmas, but that’s not karma-yoga.

So Sri Krishna was highly critical of the over-emphasis on Vedic rituals, and he comes back to that criticism one more time here. Yadā—when, O Arjuna, te buddhi—when your mind, when your thinking is shruti-vipratipannā, when your mind is turned away from seeking heaven and a better rebirth through the performance of Vedic rituals, and when your mind is nishchalā—in the second line, unwavering.

Unwavering in what sense? When your mind, sthasyati, when your mind is established—third line—samādhau achalā. We have to break those words apart: samādhau achalā. When your mind is sthasyati, established samādhau, in samadhi, achalā—unwavering samadhi.

When your mind is established in samadhi—we saw the same expression back in verse 44, and when we had that discussion, we saw the commentator’s explanation of samadhi in terms of its root meaning. And its root meaning comes from the root dhā, “to place,” with the prefixes sam and ā. So it refers to a mind that is well-placed, a mind that is well-established. And then the commentator goes on to say: a mind that is well-placed means a mind that is established in wisdom, a mind that is established in Brahman, one who is enlightened. That’s what he’s referring to here.

So Arjuna, yadā—when te buddhi, when your mind is not only shruti-vipratipannā, turned away from Vedic rituals, but when your mind is nishchalā, unwaveringly sthasyati, abiding achalā—without wavering—abiding in samadhi.

And samadhi means a state of absorption in Brahman. Being established in wisdom, being established in knowledge of Brahman, knowledge of your knowledge that your true nature, that inner divinity, we call Arjuna, that inner divinity turns out to be utterly non-separate from Brahman, the reality of universe. This is the ultimate teaching of Vedanta. This is the teaching revealed by the Mahāvākya, tāt-twam-asi. Tāt, that Brahman, the reality because of which the universe exists, twam-asi is your true nature. Arjuna, when your mind is established in that highest truth, in the truth that your individual self is absolutely non-separate from the whole, separate non-separate from Brahman, tātā, then Arjuna, Yogam avāpsya-si. Then avāpsya-si, you will gain, and the senses you will gain perfection in Yogam. Yoga, here karma-yoga is our topic. You will gain perfection of Yoga, you will achieve the goal for which the practice of karma-yoga is intended. Your practice of karma-yoga will culminate in the discovery of this ultimate truth. The truth that your inner nature, the inner divinity atma, is utterly non-separate from Brahman, the reality of the cosmos. It will be much more that we’ll see. We’ll see that teaching and trying to think of where we’ll see it next. We’ll see it a bit in chapter 6. We’ll see it, I think in chapter 7 and 9. So we’ll see that in later chapters. With this verse, Sri Krishna concludes his first Upadehsha, his first teaching of karma-yoga. He’ll continue in chapters 3, 4 and 5, and return to it once again in chapter 18.

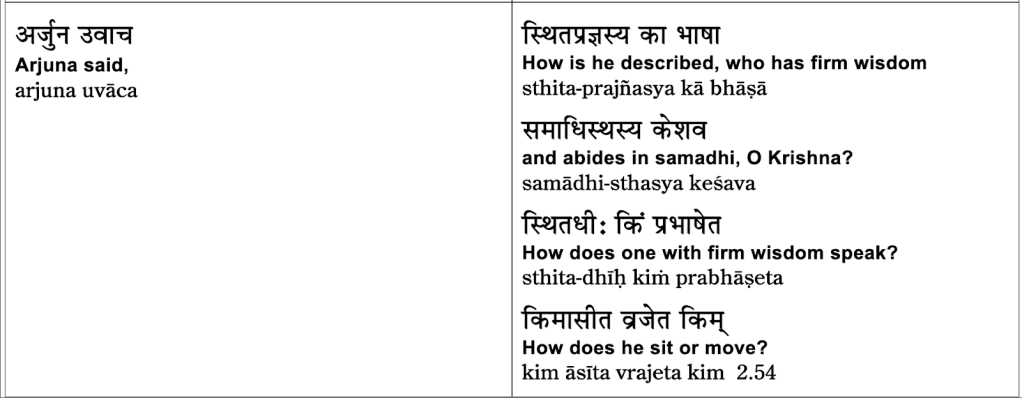

Now, this verse leads to Arjuna’s question, which introduces the next topic. And what introduce what makes Arjuna what puts a question in Arjuna’s mind are these words Nishchala Buddha-hi and Achala Buddha, a mind which is unmoving, a mind which is absolutely fixed Samadhao in Samadhi. So this language, these words that Sri Krishna uses, leads Arjuna to wonder, well, when your mind is fixed in Samadhi, how do you function in day-to-day life? It’s a good question.

If your mind is absorbed in Brahman, if you are absorbed in a state of Samadhi, then how can you walk and talk? How does an enlightened person function in day-to-day life? And this is this is not just Arjuna’s question, this is everyone’s question. People have a lot of funny ideas about what it is to be enlightened. Some people think that somehow an enlightened person looks different than other people.

Maybe they have this brahma varchas, this glow, spiritual glow with children, I joke with them that an enlightened person is someone who glows in the dark for children, the joke. Clearly that’s that’s just silly. But some people have some funny concepts, silly concepts about what it is to be enlightened. And that is exactly what Arjuna’s question is about. And let’s see Arjuna’s question here.

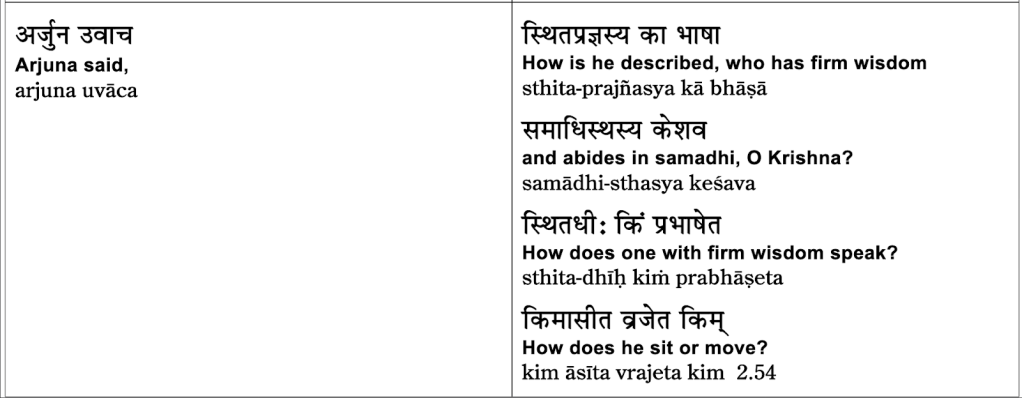

He says,

So Arjuna’s question is kā vāsha, what is the description? sita pragyasya of one whose pragya wisdom is sita firmly established. So in a previous verse, Sri Krishna used the word buddhi for intellect or understanding. And now Arjuna instead of using the word buddhi as Sri Krishna did, Arjuna’s using the word pragya, almost the same meaning, both meaning wisdom. So Sri Krishna was talking about wisdom using the word buddhi, now Arjuna’s using the word pragya to talk about the same enlightened mind. So sita pragya is a person whose mind is firmly established in that wisdom. So we saw the words nishchila, unwavering, achala, unwavering in a prior verse.

So all of that is an Arjuna’s mind leading to this question, sita pragyasya, kābhasha, o krsna, how do you, Keshava, he addresses, krsna, o krsna, kābhasha, what is the description sita pragyasya of this enlightened person whose mind is firmly established, samadhisthasya, the person who is samadhi stha, the person who is established in this state of samadhi. You can see Arjuna’s question, if an enlightened person is established in samadhi and this condition is nishchila, unwavering, achala, unchanging, then how will that person function? Look at the consequence here. If the enlightened person is so absorbed in brahman in samadhi, how will that person, not only function in day to day life, how could that person teach? Krsna is teaching. And look at the consequence, I said just a moment ago, is this, if enlightened people are always continually so absorbed that their minds are fixated in samadhi, therefore they can’t teach. The consequence is that whoever teaches is not enlightened and that would include Sri Krsna so that obviously can’t be the case but you can see the sense of Arjuna’s question.

He goes on, Arjuna says, stittadhi is a synonym for stitta pragya, one whose dhi intellect is titta firmly established in samadhi, firmly established in brahman, stittadhi that one who is firmly established in wisdom, kim prapasheta, how would they speak? If they’re so absorbed in brummin, eyes closed and in deep samadhi, they’re not going to say anything. kim a sita vrajayita kim, how would they say, interesting, kim a sita vrajayita kim, kim a sita, how would they sit, vrajayita kim and how would they move about? First of all, how would they sit, I just be totally silly here, that enlightened person is so elevated, spiritually elevated, clearly their body is not going to touch the ground. So how would they sit, their body would be hovering a few inches over the ground. vrajayita kim, how would they move about? Would their feet touch the ground or would they just sit, absorb in samadhi and not move about at all.

So these are Arjuna’s questions about the nature of the enlightened person, and as I said, it’s not just Arjuna who has these questions, it’s everyone who has these questions, and it’s important too.

Just before we see Sri Krishna’s response, consider this: if you have an unclear idea of the goal you seek, won’t that affect your pursuit? For example, if you’re driving a car and you’re not clear about the destination you’re trying to find, that lack of clarity can make you get lost. It’s crucial that you be very clear in your mind about the goal you seek.

Here, the goal is enlightenment. And if you are unclear about the nature of enlightenment, that lack of clarity can certainly cause you to lose your way, as it were, on this spiritual journey. So it’s crucial to be clear about the goal. Here the goal is enlightenment—an enlightened person.

What is the nature of an enlightened person? Of course, here—just to steal Sri Krishna’s thunder, as it were, a little bit—Arjuna asked about how does an enlightened person behave. And Sri Krishna’s answer is not going to be about how an enlightened person behaves, but rather about how an enlightened person thinks. Notice, Arjuna’s question was a little bit misdirected. Arjuna says: how does an enlightened person act, how do they behave? Arjuna, having made the assumption that the enlightened person looks and behaves different from other people, Sri Krishna is going to correct him, and show how an enlightened person doesn’t look or behave differently from anyone.

What distinguishes an enlightened person is not the behavior. What distinguishes an enlightened person is what goes on in the enlightened person’s mind—in particular, what motivates an enlightened person’s behavior. Let’s see Sri Krishna’s answer here. We’ll just begin the section.

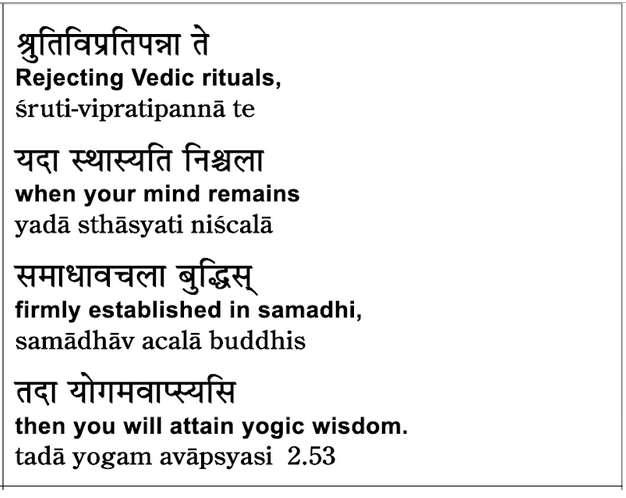

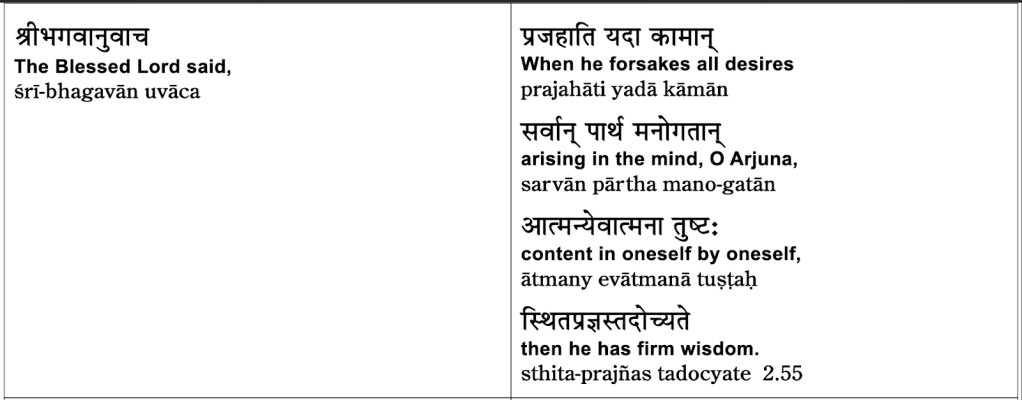

And for Sanskrit students, one more time: yadā, tadā. Yadā—when, in the first line, and in the third line (it’s buried, fourth line), sthita-prajñaḥ tadā ucyate. So it’s buried there. Yadā, tadā—when, then.

So, Sri Krishna’s response. Arjuna asked: how does the enlightened person behave? And Sri Krishna basically ignores the question about behavior. It’s a little bit like when a two-year-old asks a really silly question: “Mommy, why is the sky blue?” If mommy is smart, she’ll ignore the question—the two-year-old won’t understand anyway. So that’s basically what’s happening here. Arjuna has asked a misdirected question, and Sri Krishna very skillfully directs his discussion in the right direction.

Yadā—when. We have to combine these words all scattered. Yadā—when. When the person, when prajñaḥ tadā, when that enlightened person—prajñaḥ tadā renounces, abandons, casts off, removes—any of those meanings. When the enlightened person, prajñaḥ tadā, gives up kāmān—desires. Sarvān—all. Sarvān kāmān—all desires. Manogatān—which are in the mind, which are born in the mind. When the enlightened person gives up all desires.

Now, just a few verses back, I said: you cannot willfully give up desires. And certainly, that’s not what Sri Krishna is implying here. When an enlightened person becomes utterly free of all desires, utterly free of all rāga-dveṣa, utterly free of all that compulsivity. And how do you become utterly free from desire? We said before that rāga-dveṣa and contentment are opposites, they are enemies. Wherever there is rāga-dveṣa, there is no contentment. Conversely, wherever there is perfect contentment, there is no rāga-dveṣa. If you are in a state of perfect contentment and peace, what can compel you to do anything?

Remember, our use of kāma here is kind of more technical. Kāma in general means desire. But here we’re talking about desire not in a general sense, but in this specific sense. Pūjya Swami Dayananda, my guru, used the adjective binding desires. He separated desires into two categories: binding desires and non-binding desires. Non-binding desires we often call preferences.

You have a preference for one thing, but if it’s not there, it’s okay. For example, you might have a preference for one kind of rice over another kind of rice. Some people are fussy and they want only this basmati rice, but most people are not so fussy. They may prefer one kind of rice over another, but if they can’t have that particular kind of rice, thīk hai, it’s okay, no problem. That’s a good example of a preference as opposed to a binding desire.

I didn’t tell the Fruit Loop story—I didn’t tell. Allow me to tell this story. This is a story I made up to show the difference between binding desires and non-binding desires.

So here, kāma, that Sri Krishna is talking about, are binding desires. The story I made up is of a toddler, a three-year-old, four-year-old, who in the morning goes to the kitchen to get breakfast. And breakfast for this toddler is cereal. But the toddler has a particular kind of cereal they want—this cereal called Fruit Loops.

So this toddler climbs up on the cabinet, and in the cabinet are ten boxes of cereal. Mom has stacked them up very nicely. The toddler examines each box. None of them are Fruit Loops. And the child starts to cry. Why? Because the child has a binding desire for Fruit Loops.

A binding desire is one whose non-fulfillment causes suffering. I’ll say that again: a binding desire is a desire whose non-fulfillment causes suffering. And this child is suffering. Why? There’s no Fruit Loops—binding desire.

Suppose mom comes to the kitchen later, also for breakfast. And she also wants Fruit Loops. And she goes to the cabinet. There are ten boxes of cereal. There are no Fruit Loops. What does mom do? She chooses another kind of cereal, because mom’s desire for Fruit Loops was a non-binding desire. She has a preference for Fruit Loops. So you can see that for mom, the non-fulfillment of her desire did not make her suffer.

That’s the difference between the non-binding desire of mother and the binding desire of the child. And when Pūjya Swamiji described all this, he said: non-binding desires are not a problem. You can have hundreds and thousands and millions of non-binding desires, and if none of them are fulfilled, you’re absolutely okay—no suffering at all. But look at the contrast. You can have millions of non-binding desires, all of which are unfulfilled, and you’ll be absolutely okay. But if you have one single binding desire—just one—that remains unfulfilled, you’ll suffer. You see the difference? Tremendous difference.

So our use—Sri Krishna’s use—of the word kāma here is in the sense of that binding desire. So far we’ve been using the terms rāga and dveṣa. Rāga and dveṣa are binding desires. Rāga is a binding desire to get what you want. Dveṣa is a binding desire to avoid what you don’t want.

So here, nice—when I remember Pūjya Swamiji teaching that particular point, what a wonderful point he made. Let me just—I don’t think we’re going to go on with this verse. We’ll come back to this verse in our next class.

But let me make a further observation about Pūjya Swamiji’s distinction between binding desires and non-binding desires. He had a very nice way of teaching this, by saying that the teachings of Vedanta help you convert all your binding desires into non-binding desires. What a brilliant way of putting it! Which is to say: that the child has this binding desire for Fruit Loops. As the child grows up, that will no longer be a binding desire. The child will come out of that binding desire. The child will outgrow the desire for Fruit Loops—the binding desire. The child may continue to prefer Fruit Loops, like mother might prefer Fruit Loops, but the child will have outgrown the binding desire for Fruit Loops.

Look at this: the teachings of Vedanta help you outgrow all your binding desires. And there’s a process. And by outgrowing all your binding desires, a binding desire that’s outgrown is no longer a binding desire. It is now a non-binding desire. And the process through which you outgrow a binding desire—this is very important—you outgrow one desire by finding something you want more.

And just—how’s it? This is another way of explaining it. Suppose a child wants a bicycle. First, I think the child has a tricycle, a three-wheeler. But the child now is grown up, and now the child is five, six, seven years old. The child wants a bicycle. So when the child gets a bicycle, the binding desire for the tricycle is outgrown. You outgrow the binding desire for the tricycle by finding something better—the bicycle.

Then when a child gets a little older—actually if the child is growing up in India—when the child gets to be about 16, 17, 18, the child will want a scooter. So then, when a child gets a scooter, the binding desire for the bicycle will be outgrown, and now there will be a binding desire for the scooter. If the scooter is stolen, the child will cry. The 18-year-old will cry.

Now, eventually the child—the 18-year-old—gets older and gets a job, and wants to get rid of the scooter and get a car. So the child, now an adult, will overcome the binding desire for the scooter when they buy a car. Of course, the first car you buy is usually a little one. I think in India this is a Maruti. So the binding desire for the scooter will be overcome when you get a little car, a Maruti. And then there’s a binding desire for the Maruti, which will be overcome when you get a better car. A very—I think everyone talks about getting a Mercedes Benz in India, I suppose it’s a big deal. So the binding desire for the Maruti will be overcome when you get the Mercedes Benz.

Now, I’m setting up these steps to show a process. You overcome a particular desire, a particular desire for a particular object which you imagine to be the source of happiness. Watch this logic. The child desires the tricycle because the tricycle is imagined to be a source of happiness. Like the Fruit Loops are imagined to be a source of happiness, the tricycle is imagined to be a source of happiness. Then the bicycle is imagined to be a better source of happiness. Then the scooter is imagined to be an even better source of happiness. The Maruti, the little car, is imagined to be an even better source of happiness. And finally, the Mercedes is imagined to be an even better source of happiness.

So you outgrow one apparent source of happiness by finding another better apparent source of happiness. Notice my use of the word apparent, because you already know very well that the true source of happiness is your innate nature as sat-cit-ānanda ātmā. The true source of happiness lies within. Of course, the child doesn’t know, and even most adults don’t know, and that’s why adults are buying new cars all the time.

Here’s the conclusion. If you outgrow one apparent source of happiness by finding a better source of happiness—watch this—you will outgrow all sources. You’ll outgrow all of them. You’ll outgrow all desires by finding the true source of happiness within. That’s what Sri Krishna is describing here.

The enlightened person outgrows the desire for any and all objects of happiness in the world—anything. Object of happiness means anything that you imagine can make you happy. The enlightened person outgrows them all by discovering the true source of happiness within, by discovering one’s own innate nature to be perfect, full, and complete—discovering one’s true nature as sat-cit-ānanda ātmā.

That’s what Sri Krishna is describing here, and we’ll return to this verse in our next class. The enlightened person outgrows them all by discovering

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

ॐ असतो मा सद्गमय ।

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय ।

मृत्योर्मा अमृतं गमय ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Oṁ asato mā sadgamaya

tamasomā jyotir gamaya

mrityormāamritam gamaya

Oṁ śhānti śhānti śhāntiḥ

Om,

Lead me from the unreal to the real,

Lead me from darkness to light,

Lead me from death to immortality.

May peace be, may peace be, may peace be.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti. Om, Tat Sat. Thank you.