Gita Class 017, Ch. 2 Verse 48 – 50

May 1, 2021

YouTube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?si=pleqU_NncHLOF_Sr&v=TSe6nk-ZuEE&feature=youtu.be

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

Welcome back to our weekly Bhagavad Gita class.

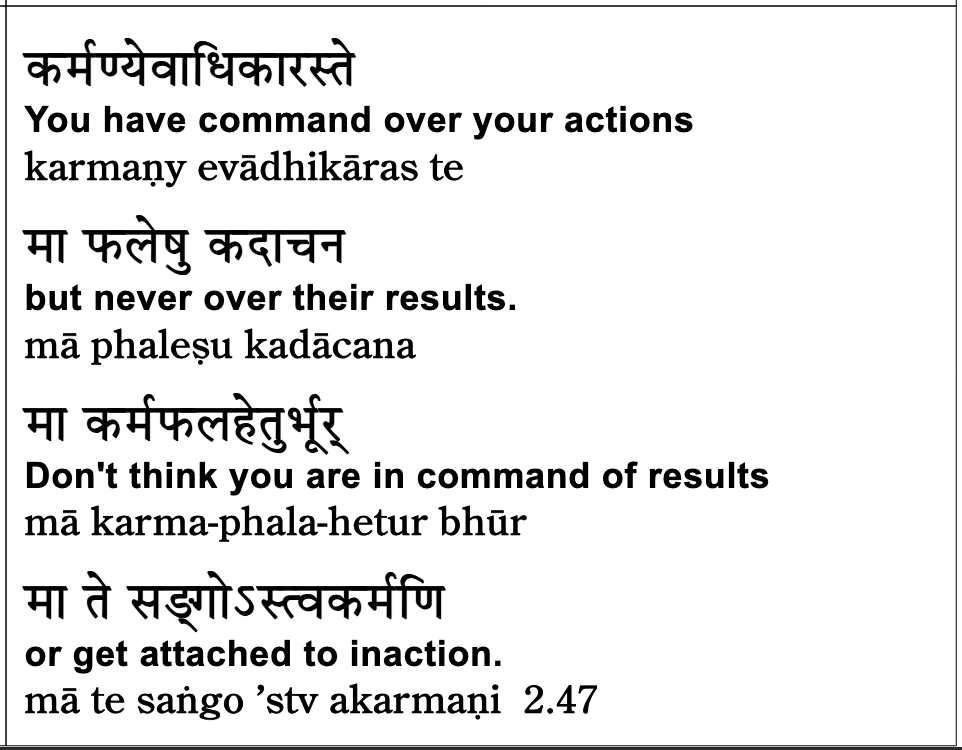

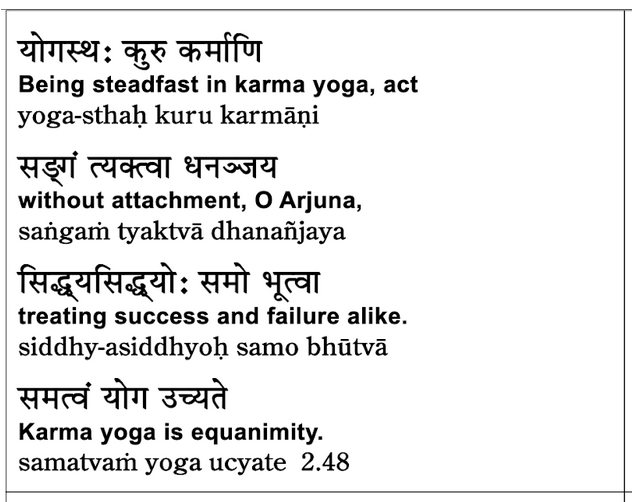

We continue on chapter 2 where the topic of Karma Yoga is introduced for the first time. We’ll start with some recitation a few verses beginning with verse 47. Please glance at the translation and then repeat after me.

There is a typo at the end of the third line there. Bhuddhis and that Tadayoga should not be there.

Okay, let us return to where we left off. In the prior class we saw the most arguably the most important verse with regard to Karma Yoga. The verse at every one quote, Same is often translated,

you have Adhikara, not the Hindi meaning of right but the more Sanskritic meaning scope of authority. You have a scope of authority over your actions, you have control over your actions, Ma Paleshukadachana but not over your actions.

And with this verse Sri Krishna introduces the topic of Karma Yoga and let us make sure that we have got the basics clear in our minds. Otherwise none of this makes any sense.

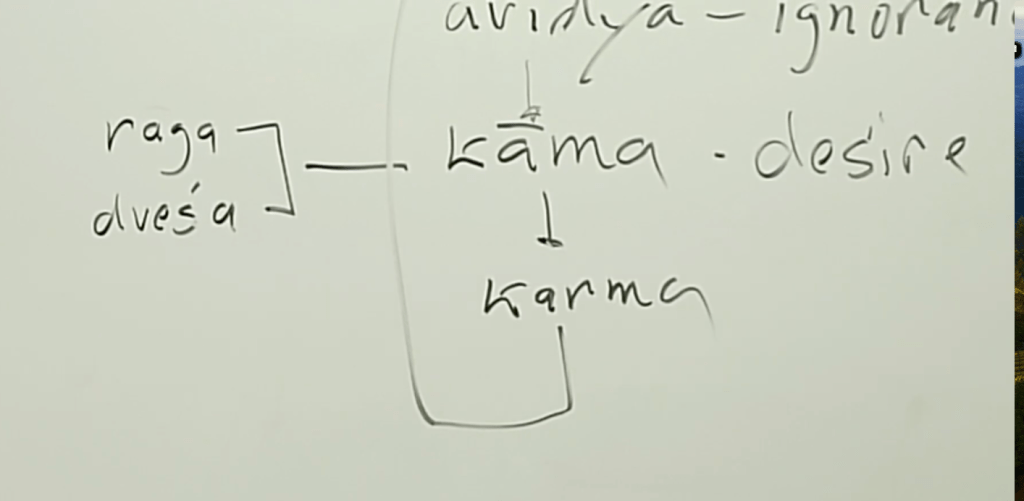

Karma Yoga is a, the definition is important. Karma Yoga is a set of attitudes through which your ordinary day-to-day activities are converted into a kind of Sadhana, a kind of spiritual practice. And the way it works, the basic way it works is by reducing the power of Raga and Dvesha over your behavior.

Raga is a compulsion to chase after what you want. Dvesha is a compulsion to run away from what you don’t want. So they’re both forms of desire. Raga is a desire to get something. Dvesha is a desire to get away from something and as long as your life is molded by Raga and Dvesha, there’s no hope of progress on a spiritual path. No hope at all. In fact, Raga and Dvesha keep you trapped in a life of worldly suffering and let me show you how.

There’s an important connection I haven’t shown you yet. I’d like to go to the board and show you exactly how Raga and Dvesha trap you in this life of worldly suffering.

So we speak of instead of Raga and Dvesha, the more general word Raga is a set compulsion to get what you want. Dvesha compulsion to avoid what you don’t want.

So you see the mutual dependence. You won’t get free from kama until you get rid of avidya. And you can’t get rid of avidya ignorance unless you have the prerequisites for making progress on the spiritual path. And one of the many prerequisites, one of which is becoming relatively free of Raga, Dvesha.

The simple way to understand it is, as long as Raga and Dvesha molds your life completely, where is the scope for spiritual life? You’ll be so engaged in worldly activities, there’s no scope whatsoever for spiritual life.

So here is the basic pattern and it shows the basic pattern of being stuck in a life of worldly suffering and being born again and again. Notice the centrality of kama, Raga and Dvesha. It’s in the middle of the problem.

It has to be addressed.

Okay. And before I remove that from the board, Raga, Dvesha is to become free from that Raga, and karma yoga is for the sake of becoming free from Raga and Dvesha. How does that work? Instead of being motivated by Raga and Dvesha, karma yoga is a set of attitudes that change your motivation. They change your attitude towards your worldly activities.

So very important — we talked about this in a prior class — karma yoga is not what you do. If what you do is help people, helping people is not necessarily karma yoga. So someone who helps people for the sake of personal gain, they want to be famous, or they want to feel good about themselves, or they’re paid very well for helping people… You get the point. Helping people is not karma yoga. Karma yoga is not what you do. Karma yoga is the attitude with which you carry out your daily activities.

So, we just saw in verse 47 that we saw at length with the whole of the last class — was spent discussing verse 47, very important verse — and it gives us two crucial attitudes, two of many crucial aspects of the set of attitudes that form karma yoga. One of which is, if you have no control over the results, if you have control over your actions, if you have no control over the results, you start to realize the limits of what you can accomplish in life. You start to realize that you are not the master of your life.

There are so many factors that you have no control over. This recognition of your fundamental incapacity to create a life of contentment and peace.

I remember vividly as a young man. So, I was working as a computer engineer in California in the 1970s, and I had worked very hard to get the degree and training and get a good position, and I thought, once I get there — so first of all, I went to California, beautiful place, and I finally made it to California. I had a great job. I had a beautiful house up on the hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean. I thought I had everything, and I discovered I was miserable.

That’s an important recognition. I worked very hard to get there. The recognition that as hard as you work, or as smart as you work, or both, obviously, as hard as you work, it is absolutely impossible to create a life of perfect contentment, peace, happiness, and joy. It is simply impossible.

This recognition is what’s conveyed in the first half of this verse. This understanding leads to a major conversion in your attitude. You realize that if what you want — not if, since what you want — is perfect peace and contentment, not a little bit here and there, but perfect peace and contentment, when you recognize that perfect peace and contentment cannot be gained through worldly efforts… That’s what leads to this conversion where you now become focused on spiritual growth. Your focus shifts from worldly efforts for happiness. You shift to seeking spiritual growth for the sake of Moksha, liberation. So that is conveyed in the first half of this verse.

Also, Ma karma pala hetu bhur — don’t think that you are, that the results of your actions are in your hands. We discussed at length — we’ll just recap it very briefly. The results of your actions come according to the laws of the universe, including the laws of karma. And those laws, as we discussed at length, those laws are expressions of Ishwara’s intelligence. The creator of the universe created the laws of the universe, including the laws of karma.

So therefore, the laws that govern the universe are expressions of Ishwara, the creator — expressions of Ishwara’s intelligence. Therefore, we can say that you commit actions. The results of those actions come to you according to the laws of the universe, according to Ishwara’s laws. Figuratively speaking, you receive the results of your actions from Ishwara’s hands, so to speak. The results of your actions are in Ishwara’s hands.

This is the second attitude conveyed here in verse 47. And don’t think of this as being something philosophical. There’s a lot of philosophy and a lot here. But this actually points to something very fundamental — a fundamental spiritual practice of prayer.

Let me introduce this point in a funny way. How often do you pray? From time to time, hopefully you’ll say some prayers in the morning, maybe in the evening, maybe perhaps during the day. But look at this — what Shree Krishna teaches in this verse can bring a prayerful attitude to every single act you commit.

Whenever you do something, you can reflect on what Shree Krishna teaches here and realize that you’re doing the action. The result comes from Ishwara. That appreciation is an act of prayer. Suppose whatever you do throughout the day, you appreciate the fact that Ishwara is the karma phala data, the giver of the fruits of actions, which then brings to you a prayerful attitude towards that action.

How many actions do you do in a day? How many deeds? Hundreds and thousands. And if you maintain this attitude throughout the day, you will have hundreds and thousands of opportunities for prayer. What a powerful spiritual practice that is — to go on praying throughout the day.

A famous verse in the Bible of all places says to “pray without ceasing.” Well, to pray without ceasing doesn’t mean to keep your hands folded throughout the day. It means to adopt this attitude where you recognize Ishwara as the karma phala data so that while you’re engaged in every single action throughout the day, you maintain a prayerful attitude at all times.

Okay. With that important but lengthy introduction, we can proceed.

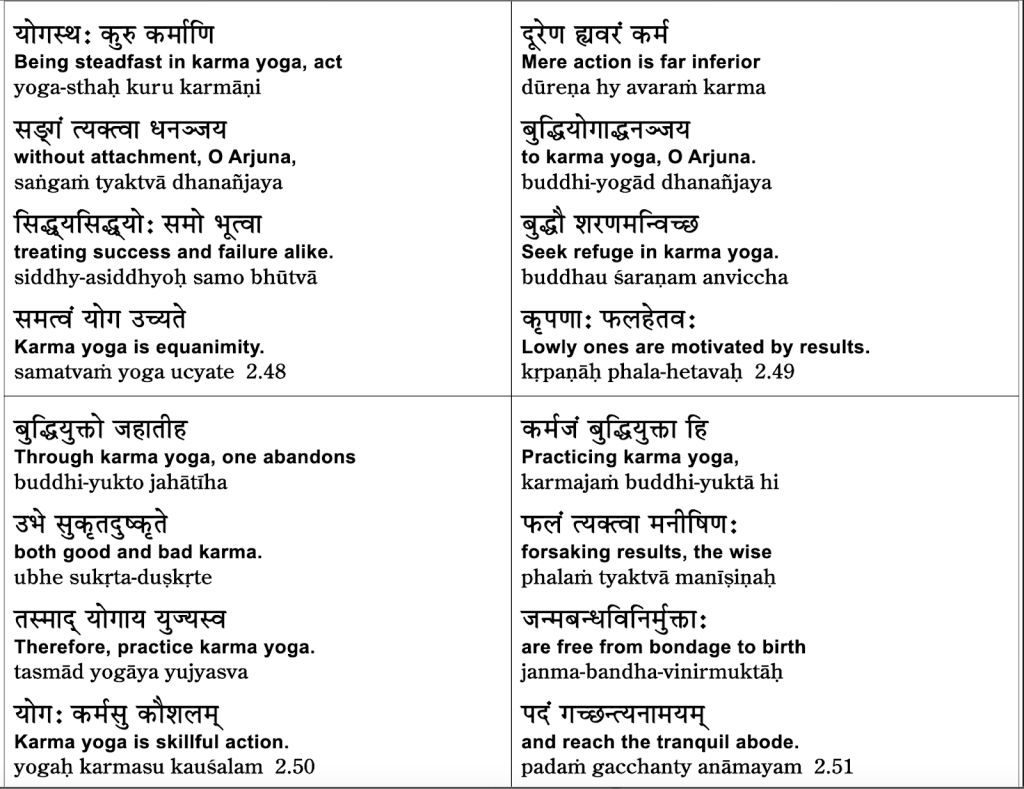

Shrikrishna here addresses Arjuna in the second line, Dananjaya — O Arjuna — Yoga-sthaḥ kuru. Yoga-sthaḥ kuru

Be established in Yoga. Yoga-sthaḥ. Be established in these attitudes — and here Yoga means karma yoga.

In chapter 12, Yoga is going to mean bhakti, bhakti yoga. In chapter 6, Yoga is going to mean dhyāna, meditation. Yoga is a very versatile term. Here, Yoga means karma yoga.

Yoga-sthaḥ kuru — be established in karma yoga. And kuru-kuru — the verb does double duty: Yoga-sthaḥ kuru — be established in Yoga, and kuru karmāṇi — do actions, do carry out your duties throughout the day.

How? Saṅgaṃ tyaktvā. Tyaktvā — having given up saṅga. Here saṅga means attachment. Attachment means desire. And here this goes back to the first of the attitudes we talked about, and that is when you recognize that all your worldly efforts will never add up to perfect contentment and peace.

What does that shift of attitude — that transformation, that conversion of attitude — do? It means you’re no longer driven by rāga-dveṣa, because why? Why burn yourself out, engaged in worldly activities that you know will never give you perfect peace and contentment? This is that major shift of attitude.

The way you overcome rāga-dveṣa, the way you overcome saṅga (attachment), is through the recognition of the fact that all your worldly efforts will never give you perfect contentment and peace.

Viveka-janya-vairāgya — oh, that’s such an important term. Allow me to put it up on the board.

We hadn’t planned to do this, but it’s quite important. This expression that I just used — Viveka-janya-vairāgya. And that’s really one big word.

Vairāgya means dispassion. Dispassion means the absence of rāga-dveṣa. Dispassion means the absence of kāma. Dispassion means the absence of saṅga, attachment.

And how does this dispassion take place? It is janya — born. By the way, these long compound words often give their meaning reading from right to left. So look at this: this is dispassion (vairāgya), which is janya — born of viveka — proper discernment.

I hope you can read that: discernment. Viveka-janya-vairāgya is dispassion born of proper discernment. That’s what we’re discussing right now. When Śrī Krishna says saṅga-tyaktvā — having given up attachment — he’s referring to that viveka-janya-vairāgya, dispassion born of discernment.

Please note that you cannot give up attachment as a matter of will. Suppose someone drinks a lot of tea, and this person comes to believe that he’s so attached to drinking tea, and that attachment is going to be an obstacle to spiritual growth. So this person decides: “I don’t want my tea drinking to be an obstacle to spiritual growth. Therefore — no more tea.”

What happens for that person? The next morning comes: no morning chai. What is the person thinking about all morning? “Chai, chai, tea, tea.” All day long, the person goes on thinking of tea.

Here’s the point: you can stop drinking tea, you cannot stop desiring tea. My point here is that desire — or rāga and dveṣa — are not a matter of will. You can’t choose to give up desire. You can overcome desire — notice the difference — you can’t choose to give up desire, you can choose to overcome desire through discernment, through understanding the limitations of that worldly desire.

So, saṅgaṃ tyaktvā — having given up attachment — kuru karmāṇi — do your actions.

Siddhy-asiddhyoḥ samaḥ bhūtvā is another sentence. Samaḥ bhūtvā — having become the same. Samaḥ bhūtvā — having become the same towards siddhi (accomplishment) and asiddhiyohoh (non-accomplishment), or simply having the same outlook on success and failure, treating success and failure alike.

How can you treat success and failure alike? In conventional life, it’s absolutely impossible. But karma yoga is not a matter of conventional life. Karma yoga requires this transformation of attitude, where you realize that conventional life doesn’t lead to perfect peace and contentment.

With that understanding, you engage in your actions — not driven by the result, by the particular result. Remember, we said your priorities shift to the extent that your first priority is mokṣa. Your highest priority is mokṣa.

If your highest… I’m thinking — I’m grasping for a metaphor here — success and failure makes me think of politics, and politicians who want to get reelected. Suppose there’s a politician who’s a perfect karma yogi. I have a feeling there is no such thing, but just for the sake of our discussion, suppose there’s a politician who’s a perfect karma yogi, and this politician wants to get reelected.

But as a perfect karma yogi, the politician’s ultimate goal is not getting reelected. The politician’s ultimate goal is mokṣa — spiritual growth that culminates in liberation. So when the election comes along, whether or not the politician gets reelected doesn’t make any difference.

That is in the next line: samatvaṃ — equanimity — samatvaṃ yoga ucyate. Yoga, yoga, yoga — here means karma yoga. Karma yoga ucyate — is said, is said to be what? Equanimity. Karma yoga is said to be equanimity.

Equanimity means treating success and failure alike. And equanimity is like our highly unusual karma-yogi politician who is so focused on mokṣa that if he wins or loses the election, it makes no difference. Because you can win the election and pursue mokṣa. You can lose the election and pursue mokṣa. In fact, you might argue that you might pursue mokṣa even more effectively if you lose.

The point is that that karma-yogi politician is not driven by worldly success. That karma-yogi politician is driven to gain spiritual growth, ultimately leading to mokṣa.

Oh, I’ve scribbled something here. It’s hard to read, but I think I’ve got it here: samatvaṃ yoga ucyate — yoga is equanimity. Please don’t misunderstand that equanimity does not mean “anything is okay, anything goes.” People have this attitude: Aṭhīḳ hai, baṭhīḳ hai, sabṭhīḳ hai — anything is okay.

Everything is not okay. People living in poverty is not okay. People suffering from disease is not okay. People being deprived of proper education is not okay.

Samatvam here has nothing to do with attitudes towards what’s going on in life — so please don’t misunderstand, you won’t misinterpret it like that.

So samatvam — equanimity here — is specifically towards your worldly activities. If you are successful or unsuccessful in any endeavor, to have equanimity towards that endeavor knowing that your ultimate goal is spiritual growth, not the successful outcome of your endeavor.

All right. Then:

And you know that I’m repeating twice so that you can recite after me — you remember that. You struck my mind.

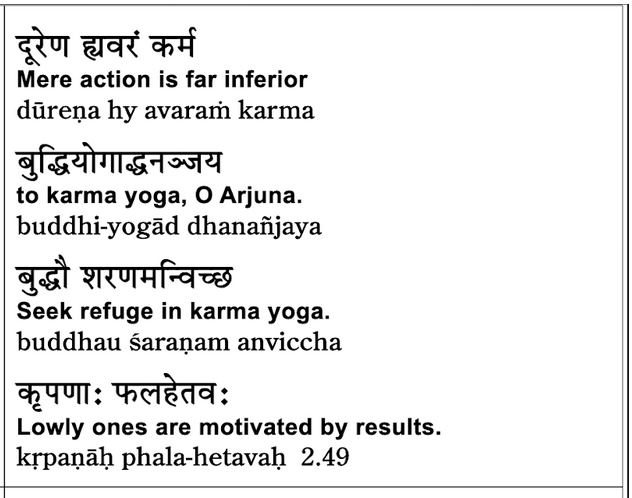

Dūreṇa — hi, break those words apart: hi avaraṁ karma, avaraṁ karma, dūreṇa avaraṁ karma.

Here karma is contrasted with karma yoga. Karma yoga, as we said before, is performing an action with this set of attitudes that convert that action into spiritual practice — sādhana.

Here the word karma refers to doing an action without the attitude of karma yoga — mere karma. And that mere karma is karma driven by rāga and dveṣa, as we saw before. Mere karma is driven by desire — or rāga and dveṣa — keeping you trapped in that cycle of birth and rebirth.

So Śrī Krishna says here that karma — the mere performance of action driven by rāga, dveṣa — is dūreṇa avaraṁ, it is far inferior when compared to buddhi yoga.

In comparison to buddhi yoga — we saw that term before — do you remember? Buddhi here means the attitude of karma yoga. So yes — karma yoga. Buddhi yoga means karma yoga in this context. It can have other meanings elsewhere, but here buddhi yoga, we saw the term before, means karma yoga.

Dhananjaya, O Arjuna — karma driven by rāga, dveṣa, ordinary mere karma driven by rāga, dveṣa — is dūreṇa avaraṁ, it is far inferior, buddhi yoga, in comparison to buddhi yoga, in comparison to karma yoga.

Why is it far inferior? Ordinary worldly activity can give you ordinary worldly happiness and contentment. Well, how stable is that ordinary worldly happiness and contentment?

You can be happy and content — and I hope you are — but that happiness and contentment can be stolen from you in any moment: a health crisis for yourself, for a family member, or some other kind of tragedy. Your investments go — end up being worthless. Or some other huge tragedy in life — any number of things — in an instant can steal away your happiness and contentment.

So Śrī Krishna here is making the point that the happiness and contentment you get through worldly endeavors is far less than the perfect happiness and contentment you can gain as a result of living a life of spiritual growth — a life that culminates in mokṣa.

And mokṣa indeed is a condition of perfect contentment and happiness which cannot be robbed from you, because when you gain mokṣa, nothing outside can hurt you, can affect you, can disturb you. You transcend — that is a nice word to use here — you transcend all worldly suffering.

Therefore, Dhananjaya — O Arjuna — remember the meaning of that word and that name, little unusual. Dhana is wealth — the one who conquers wealth. And the context is in Yudhiṣṭhira’s yajña, where you did — what was the name? — the aśvamedha yajña, where you sent the horse out. And — it’s a complex story — wherever the horse went, you were required then to invade that kingdom and conquer the kingdom and gain all their wealth. Arjuna was the principal warrior engaged in that, so Arjuna won over the wealth of so many adjacent kingdoms.

Complete side — let me come back here: O Dhananjaya, O Arjuna — buddhau śaraṇam anviccha.

Anviccha — Arjuna, you should seek. You should seek what? Śaraṇam — refuge, safety. You should seek refuge where? Buddhau — in this buddhi, in this attitude, in this attitude of karma yoga.

O Arjuna, you should adopt these attitudes of karma yoga so that your worldly activities — and for Arjuna, his activities will be for the next 18 days fighting on that battlefield — so if Arjuna fails to adopt the attitude of karma yoga, what will be the result?

The result will be 18 horrible days of warfare, fortunately culminating in their victory. But in being victorious over the Kauravas, is Arjuna going to enjoy perfect peace and contentment? It will certainly be happier than if he lost, but he will not enjoy perfect peace and contentment.

Just a moment here — look at the logic: if in order to enjoy a state of perfection, how much effort is required to reach a state of perfection, perfect peace and contentment?

Let me give you an example from science: suppose you have alcohol dissolved in water, and what you want is pure water. So what do you do? You distill the water — you boil off the alcohol to get pure water.

So every 10 minutes of boiling, you get rid of 90% of the alcohol. I’m making up these numbers just to give you an idea. So the longer you boil the water, the more alcohol you get rid of. Every 10 minutes you get rid of another 90% — then you’re 10% left — then another 10 minutes and you have 1% left — then another 10 minutes and you have 0.1% left. My numbers might be off here — forgive me — but you get the point: that continually purifying the water, the water becomes more pure and more pure.

When does it become perfectly pure? When do you get rid of the last molecule of alcohol dissolved in that water? Theoretically — and this is what in science, statistically speaking — you never get rid of the last molecule. You approach purity — remember something called an asymptotic approach — forget it, I’m getting way too scientific here — you approach purity, but you never quite get there.

That’s the problem of worldly effort: worldly effort can approach a condition of perfect peace and contentment, but can never reach there. Because the amount of effort to achieve a state of perfection is an infinite amount of effort. An infinite amount of effort can achieve a state of perfection — and an infinite amount of effort is simply not possible, therefore — buddhau śaraṇam anviccha. Therefore, Arjuna, you should seek refuge in these teachings of karma yoga.

Why? Phala-hetavaḥ. Phala-hetavaḥ are people who are motivated — hetu means cause or motivation — people who are motivated by phala, the results. People who are striving for that life of perfect peace and contentment through ordinary karma — ordinary actions driven by rāga and dveṣa — those people are called phala-hetavaḥ, those people who are motivated by results.

And here Śrī Krishna, very harshly, says: they are kṛpaṇāḥ.

Kṛpaṇa — try translating that slowly — kṛpaṇa is like a beggar. A beggar is one who is destitute and is grasping after pennies — a desperate person grasping after pennies. That is the metaphor Śrī Krishna uses to describe someone seeking perfect peace and contentment through worldly effort. In Śrī Krishna’s view, they’re like desperate beggars grasping after a few pennies. Very strong language.

Continuing:

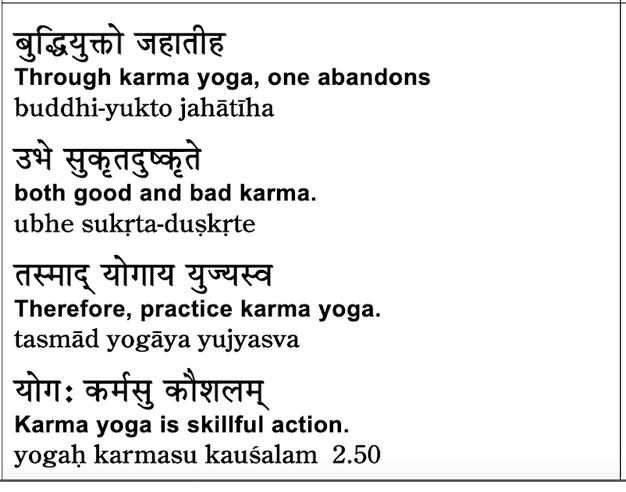

Buddhi-yuktaḥ — as one who is here (yukta means engaged), one who is engaged with this buddhi, with this attitude of karma yoga — buddhi-yuktaḥ: one who is engaged in worldly activities with this attitude of karma yoga.

What about that person? Jahātīha — iha, here in this life, that person jahāti, gives up ubhe, both of them.

Both of what? Sukṛta and duṣkṛta.

Sukṛta is the result of pious deeds; duṣkṛta is the result of adharmic deeds. This is a reference to religious merit and religious demerit — what we call puṇya and pāpa.

By doing dharmic deeds, helping people, etc., you accumulate puṇya. Puṇya here is called sukṛta. Sukṛta is a synonym for puṇya — the accumulation of religious merit through the performance of good deeds.

Duṣkṛta is pāpa. It is the accumulation of the so-called “bad karma,” religious demerit, which you get as a result of adharmic actions like hurting people.

Now here, Śrī Krishna is addressing a more religious person. So far, we’ve been talking about efforts in daily life for the sake of peace and contentment here and now, in this life. But what about in the next life?

There are many people who are so focused on what will happen in their next life that they get highly engaged in performing rituals in this life to accumulate good karma (sukṛta), and they’re very concerned about avoiding any adharmic duṣkṛta because they’re afraid that it might prevent them from having a better rebirth or going to heaven.

This is another attitude. Most people are focused on happiness and contentment — perfect happiness and contentment — here in this life. But there are also people who are focused on the next life, gaining a condition in their next life where they enjoy perfect peace and contentment.

And Śrī Krishna says here that if those people were karma yogis, they would stop worrying so much about the next life. Please notice that it’s actually a very worldly attitude to focus on accumulating religious merit and avoiding religious demerit.

To focus on that is not a spiritual attitude at all — it’s a very worldly attitude, is it not? It’s like accumulating money in your bank account and avoiding expenses. The only difference is that that account is going to help you not in this life, but in your next life.

So, someone in this life who spends all their time putting money into their bank account, never spending anything — such a person is a miserable miser. What kind of life is that?

Well, the same can apply to someone who is so focused on pious acts — like doing rituals — that they’re also like a miserable miser. Only, instead of worrying about this life, they’re focused on the next.

Śrī Krishna says that when you adopt the attitudes of karma yoga, you give up focusing your goal on the next life.

Remember when we talked about the four puruṣārthas — dharma, artha, kāma, mokṣa — which I keep putting in a different order.

Kāma — pleasure now.

Artha — wealth, for the sake of later pleasure.

Dharma — religious merit, for the sake of pleasure in your next life.

And Śrī Krishna says here: you should give up all three of those — focusing on kāma (pleasure now), focusing on artha (pleasure later in this life), and focusing on dharma (religious merit for the sake of pleasure in your next life).

Jahāti — the karma yogi gives up focusing on all three of these and focuses on the fourth puruṣārtha, the parama puruṣārtha, the ultimate goal of life, which is mokṣa.

Tasmād, therefore, Arjuna — yogāya yujyasva.

Arjuna, yujyasva — you should be engaged. Engaged in what? Yogāya — in yoga. And again, yoga here means karma yoga.

In chapter six, it means meditation. In chapter twelve, it means devotion. But here in chapter two, and again in chapter three, yoga means karma yoga Hu Arjuna, you should engage yourself in karma yoga.

And again, karma yoga is not what you do.

What is Arjuna going to be doing after this discussion with Śrī Krishna is over? What will Arjuna do later in the day?

Remember — this discussion takes place on the morning of the first of the 18 days of battle. What is Arjuna going to be doing later in the day? He’ll be engaged in warfare and mortal combat. But Arjuna can be engaged — which happens to be his duty, as we’ve discussed at great length — yes, Arjuna has the opportunity to be engaged in his duties with this attitude of karma yoga.

Look at this: karma yoga can convert even a horrible act like mortal combat — it can be transformed into spiritual practice.

How powerful is karma yoga? If karma yoga can transform ordinary actions into spiritual practice, karma yoga is so powerful it can even convert mortal combat into a form of spiritual practice.

Why? Yogaḥ karmasu kauśalam.

Also badly mistranslated — the simple meaning, of course, is “yoga is kauśalam,” skill; karmasu — in action. “Yoga is being skillful in the performance of your actions.”

Don’t be simplistic here — and I know you won’t be — but if there’s a very skillful thief, is that skillful thief performing karma yoga because he’s doing it skillfully?

Here, the skill is not the skill of doing the action. Here, the skill is clearly the attitude with which the action is being done. So karmasu kauśalam — yoga is a particular skill brought into the performance of action.

And here, the skill is one of attitude — to be engaged in your actions not driven by rāga and dveṣa, as conventional karma is, but to be engaged in action based on these attitudes of karma yoga.

We started back in verse 47 — we saw the attitudes of karma yoga:

- Recognizing that your ultimate goal is not being successful in whatever deed you’re doing.

- Recognizing the limitations of what you can accomplish through your worldly efforts.

- Recognizing that your ultimate goal is mokṣa.

And with mokṣa as your overriding priority in life, your attitude towards all the individual deeds you have to perform gets tremendously transformed.

The pressure is off — you’re not driven to be successful like our karma-yogi politician. You’re not driven by rāga and dveṣa. You are driven, but you’re driven to gain spiritual growth, you’re driven to gain mokṣa.

Another aspect of this attitude of karma yoga we discussed was this prayerful attitude — to be engaged in your activities with this sense of…

Just before we conclude, one more aspect: when we look at Īśvara as karma-phala-dātā, as the giver of the fruits of actions — when I, right now, am engaged in the action of teaching, I recognize very well I have control over what I teach. I have no control over whether it’s understood or not.

So this is an example of karma yoga — my ability to communicate effectively is really in Īśvara’s hands. Whether or not my words are understood, whether they really go in — it’s not in my hands, it’s in Īśvara’s hands.

So every time I sit to teach, I have a prayerful sense, a prayerful mood, because I recognize that the effectiveness of anything I teach is in Īśvara’s hands.

Further — this is not really what’s taught here, but further — my ability to teach is also in Īśvara’s hands; it’s a blessing of Īśvara’s. Everything is a blessing from Īśvara’s.

This part we can talk about — it’ll come later, like in chapter 10. So anyway, we’ll discuss all of this later.

The point is that the attitudes of karma yoga include developing a prayerful sense about whatever you’re engaged in so that you know that Īśvara is present here and now with me as the karma-phala-dātā, as the hands from whom I will receive the results of my efforts, of my actions.

We’ll see more in next classes

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti. Om, Tat Sat. Thank you.