Gita Class 016, Ch. 2 Verse 47

Apr 24, 2021

YouTube Link: Bhagavad Gita Class by Swami Tadatmananda – Ch.2 Verse 47

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

Good. Welcome back to our weekly Bhagavad Gītā class.

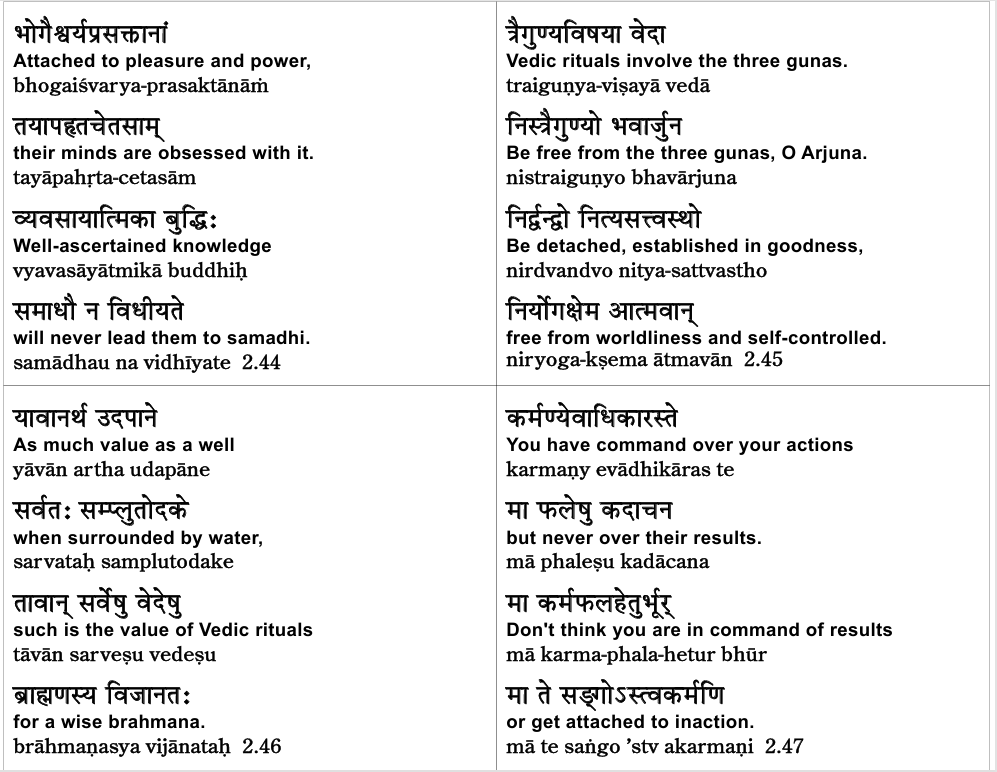

We continue our study in Chapter 2, and we take up in earnest the topic of Karma Yoga starting with today’s class. We begin with some recitation, as always, beginning with verse 44. Please glance at the translation as I’m chanting, and then recite—repeat—after me.

Chanting:

That’s a good place to conclude our chanting.

Well, we came right up to, and didn’t begin—oops, verse 40. One too far. Sorry—let me get back here… there we go.

Śrī Krishna has been introducing Karma Yoga in the last several verses, and he made it very clear that Karma Yoga is not the performance of rituals.

As we discussed, the word karma in ancient times meant Vedic rituals. So Śrī Krishna wants to make it very clear—Karma Yoga is not the performance of Vedic rituals. In fact, as you saw, he is quite critical about an overemphasis on the performance of rituals.

Then we also discussed how Karma Yoga is not merely doing your duties. I don’t know how people got that idea. Merely doing your duties is like the minimum requirement to be a good person—it doesn’t make you a sādhaka, a spiritual aspirant.

Also, as you know, many people do their duties and go on complaining all the time:

“Oh, I’ve got to do this. I’ve got so much to do. I’ve got no time.”

Well, to do your duties with that attitude is certainly not Karma Yoga.

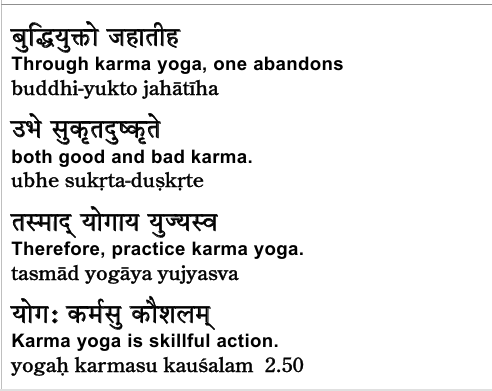

In fact, as we discussed before—and as we’re going to see today—Karma Yoga is not what you do. Karma Yoga is the attitude with which you do whatever it is you do. And that attitude, in particular, is meant to transform your ordinary activities into a spiritual practice.

That really is, so simply, what Karma Yoga is. Karma Yoga is a set of attitudes—not just one, there are several—attitudes which you can adopt, and thereby transform your ordinary day-to-day activities into a kind of spiritual practice.

Note that our ordinary day-to-day activities are driven by rāga and dveṣa, as we discussed before.

- Rāga is literally translated as “passion” or “desire,” but it is more like a drive or compulsion—the definition we’ve used here: a compulsion to chase after anything that you think will give you pleasure.

- Dveṣa is also a compulsion—a compulsion to run away from anything that you think might deprive you of pleasure or cause you suffering.

Our conventional day-to-day activities are driven by rāga and dveṣa—these two compulsions: to go toward something, or to run away from something.

Karma Yoga, in the most basic understanding, is a set of attitudes through which you remove that compulsivity of rāga and dveṣa which motivate actions, and replace it with a whole new set of attitudes and motivations—which we’re going to see in the next few verses.

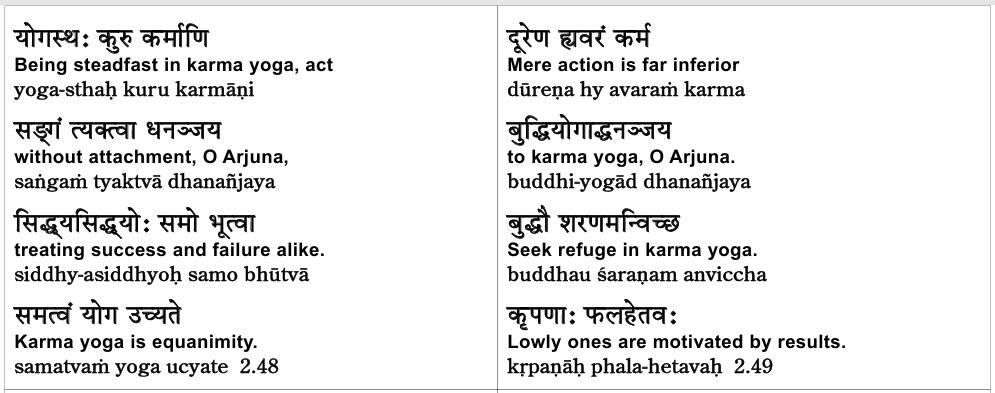

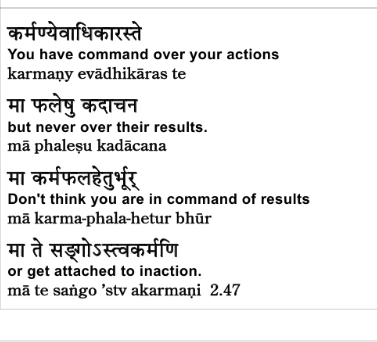

So, let us begin with—already on the screen—the most widely-quoted verse in the Bhagavad Gītā is perhaps this one. And it also happens to be the most widely mistranslated verse, which we’ll discuss in just a moment.

Karma Yoga, in the most basic understanding, is a set of attitudes through which you remove that compulsion. We’ll see the mistranslation right at the beginning:

Karmaṇy-evādhikāras te—for you (te), you have adhikāra, and that’s the word that gets mistranslated. Almost always—well, not almost always, but too often—you’ll see it translated as “right.” Te, “you have adhikāra”—a “right.” Karmaṇi eva te, we have to break the word. So far: you have a right over karma, “actions,” eva, “alone.”

Mā phaleṣu—but you have no adhikāra, you have no right—phaleṣu mā, you have no phala, no right to the results of your actions—kadācana, “at any time.” So, or mā kadācana—you never have adhikāra, a right to the phala, the fruits of your actions.

To paraphrase the mistranslation:

“You have a right to your actions; you never have a right to the results of your actions.”

I’ve never even understood what that means—having a right to actions or a right to the results.

The confusion here has to do with the fact that adhikāra is a very common word in Hindi, and very often that Hindi meaning is used here. By the way, let me make this comment: I think having no knowledge of Hindi is a great advantage—a blessing—when coming to a Sanskrit text like this, because so many Hindi words are derived directly from Sanskrit.

So, knowledge of Hindi—many of you know Hindi—is a great benefit most of the time. But in a few places, where the Hindi meaning is very different from the Sanskrit meaning, you can get in trouble. And this is one of the places where you get in trouble—where you use the Hindi meaning of adhikāra.

Like in Hindi movies, you see an actor say:

“Yeh mera adhikār hai!” (“This is my right!”)

Well, that’s fine in a Hindi movie. But this is the Bhagavad Gītā, and it’s in Sanskrit—so let’s get the correct meaning.

The Sanskrit meaning here, adhikāra, is a little complex. I can’t think of a single word for it, but it means a scope of authority—an area over which you’re in charge, you have control. I don’t think there’s any one English word that has all those meanings, but “scope of authority” is a good meaning here. Adhikāra is a scope of authority—an area over which you have control. So therefore, with that correct meaning in mind, we can make sense out of this first half. It says—te, Śrī Krishna advises Arjuna—te “for you,” Arjuna, you have adhikāra, you have a scope of authority over what? Karmaṇi eva—over your actions alone. And to simplify it a little bit, to make it clear: you have control over your actions alone. Mā phaleṣu kadācana—but never, at any time, do you have control over the results.

Now, adhikāra doesn’t literally mean “control,” but in this context—scope of authority, an area over which you have control—in our paraphrase we can use that word “control.” So: you have control over your actions. You have no control over the results. That is a much more accurate and meaningful translation than saying, “You have rights over actions,” etc. There are no “rights” over your actions.

Of course, now we have to understand this a little further. This is a reference to the doctrine of karma. We’ve sidestepped a detailed explanation of the doctrine of karma before, but here, to understand this verse, we have to at least pick up some crucial elements of it. You have control over your actions. You have no control over the results.

Let me illustrate. Dropping this pen is my karma—my action—and I have control over dropping this pen. I can choose when I drop it: I can drop it now, or I can hold onto it longer. I have control with regard to the action of dropping it. But once I release the pen, do I have any control over the result of dropping it? No. My adhikāra, my scope of authority, ends when I drop the pen. Once I’ve dropped the pen, I have no adhikāra, no control over what happens to the pen whatsoever.

Of course, we know, according to the law of gravity, it falls downward. But I have no control over that—it’s not in my hands; it’s all due to the force of gravity, the law of gravity—one of several laws that govern the universe, along with the laws of karma. We need to explore this first of all. This is a big topic, and by the way, this is such an important verse that we may spend the majority of this class on it. This verse deserves that kind of attention.

So, look at this: I control dropping the pen. I have control over the action of dropping the pen. I have no control over the results. Who’s in control of the results? I’m in control of the action. Then who is in control of the results? It happens according to the law of gravity. Fine. But the law of gravity is whose law? Who established the law of gravity? Whose intelligence is infused in the universe that gives order to the universe? You know the answer to that question—Īśvara, God, the Creator, Sustainer and Destroyer of the universe.

It is Īśvara’s intelligence—Īśvara’s intelligent order, as my guru would love to say—according to which the universe functions. Gravity is certainly part of Īśvara’s intelligent order. So, in a manner of speaking, we could say that gravity is an expression of Īśvara’s intelligence. This is a really important teaching. Gravity is a law of nature. Nature is Īśvara’s creation. Nature functions according to Īśvara’s intelligence. So, it is absolutely appropriate to say that the law of gravity is a manifestation of Īśvara’s intelligence.

With that in mind, in a manner of speaking, we could say that I have control over dropping the pen, and then Īśvara has control over how it falls. This is what the first half of the verse is talking about: karmaṇy eva adhikāras te—you have control over your actions; mā phaleṣu kadācana—you have no control over the results. The results are not in your hands. The results are in Īśvara’s hands.

There is an important expression we use for Īśvara in the teachings of Advaita Vedānta—we say that Īśvara is the karma-phala-dātā. Karma you know—actions. Phala—the results of actions. Dātā—the giver. The giver of the results of your actions. My karma is to drop the pen. The phala is not given by me; the phala is determined and given by Īśvara.

There’s another important aspect of this, but before we get into that second aspect, let’s talk about how that orientation—understanding your limitations—is itself a spiritual attitude. You have no control over the outcome of a situation. You only have control over the action. When I use that expression “outcome,” I think about medical doctors—specifically surgeons. A surgeon goes into an operating theater and performs a really complicated, delicate surgery—like open-heart surgery, where they, pardon my language, “fix your plumbing.” They take veins out of your legs and replace the clogged arteries around your heart. This is like a plumbing job, except what you’re working with is so delicate. My mind is boggled by the skill these surgeons must have.

Here’s the point: surgeons know very well that every surgery they perform may or may not have a good outcome. The surgeon is highly skilled—tremendously skilled—but even the best surgeon on the planet cannot ensure the desired outcome.

I think surgeons are smart enough and humble enough to know that what’s in their hands is the details of the plumbing job—if we can call it that. But once they’ve done their plumbing work, the outcome is no longer in their hands. The doctor may say it depends on the patient’s state of health—the patient’s ability to recover from the surgery.

Of course, the patient’s ability to recover from the surgery would be according to the laws of nature, would it not? The patient’s ability to heal and recover—these are natural forces. Healing and recovery are governed by nature. So therefore, we can definitely say that the surgery is in the surgeon’s skillful hands, but the outcome of the surgery is in Īśvara’s hands—in the form of the laws of nature which enable the patient to heal and recover. You get the idea.

Now, this is just the first part of a series of teachings meant to change our attitudes towards what we do. And that change of attitude is what karma yoga is all about, as I said. The goal is to free us from the compulsivity of rāga and dveṣa. So, let us see how this particular teaching can help free us from rāga and dveṣa.

We are compelled to chase after what we want, and we are compelled to run away from what we don’t want. That compulsion is based on a false sense of competence. Now, what do I mean by that? A false sense of competence means we assume we can get what we want, we assume we can avoid what we don’t want, we assume we are competent to create the desired result.

Well, what does this verse say? The verse says that you’re not competent. In fact, “competent” is not exactly a synonym for adhikāra, but it is a related word. You have competence with regard to your actions, but you have no competence to produce a desired result. Yet we all labor under the false illusion that we’re in charge of our lives.

Isn’t it so? We think we’re in charge of our lives. Of course, all it takes is a sudden illness, or a traffic accident, or something else unexpected, and suddenly we get “kicked in the pants,” as you say in American English. We are brought to our senses that we’re not truly in complete control of our lives. We are in control of our actions; we are not in control of results.

Now, this is what Śrī Krishna is teaching Arjuna in the first half of the verse—and teaching all of us. We are like people looking over Arjuna’s shoulder as Śrī Krishna is talking to him in the chariot. We are receiving the benefit of all those teachings. And here, by recognizing our own limitations—by recognizing that we can only control our actions, by recognizing that we have no control over the results, that we have no competency to produce the results we want—we take the first step toward breaking free from that compulsivity.

That compulsivity—to chase after what we want and run away from what we don’t want—is based on this false sense of competency. But when we truly get it, when we realize we’re not in control of everything, that we are not the gods of our own lives, that compulsivity weakens. This is one of many teachings associated with karma yoga—one of many attitudes associated with it—that we are not fully in control of our lives.

Of course, closely related to that is this: if we’re not in complete control, who is? That brings in Īśvara, and that brings in a prayerful attitude toward our actions. Watch how this works.

When we’re engaged in… well, let’s go back to that surgeon example, because it’s a good one. When that surgeon goes into the operating theater, the surgeon does the best he or she can do. But then, having done that, he or she recognizes that the result is not in their hands.

If the surgeon is a Hindu—and by the way, in the United States there are so many doctors of Indian origin, including surgeons—it might be that the surgeon indeed is Hindu. That Hindu doctor, leaving the operating theater, may say a prayer: “Hey Bhagavān, O God, I’ve done the best I can to help this patient—to help this patient go on living. I’ve done the best I could, and now everything else is in Your hands.”

That Hindu doctor would recognize that Īśvara is the karma-phala-dātā—the giver of the fruits of actions, the giver of results. That attitude introduces a prayerful dimension into everything we do. Suppose these teachings sink in so deeply that you are constantly alert to the fact that whatever you do, the results are not in your hands—the results are in Īśvara’s hands.

Immediately, that shift of understanding will lead to a prayerful attitude toward whatever you do. You will constantly have the sense: “I am doing the best I can, and the rest is in Bhagavān’s hands—in God’s hands.” That prayerful attitude can be present in everything you do.

So that doctor may have a prayerful attitude, but wherever you are and whatever you’re doing, you can have it too. If you’re in a business meeting, you can do the best you can in making a presentation, and then you realize—the rest is in God’s hands.

And you have that sense in your heart that the rest is in God’s hands. You have that prayerful sense—the broadest sense of prayer, by the way. Any time you connect yourself to Īśvara, prayer in its most fundamental sense is being connected to Īśvara.

So here, recognizing Īśvara as the karma-phala-dātā—the giver of the fruits of your actions—that is a connection, a prayerful connection. Well, suppose that prayerful connection is present in every single thing you do. You give your presentation at work—the results are in Īśvara’s hands. You get into your car to drive home—whether or not you reach home is in Īśvara’s hands.

Suppose you thought about that when you started your car. This is, in very concrete and practical terms, what karma yoga looks like in moment-to-moment life, day-to-day life. When you turn that key—first of all, whether or not your car starts is not in your hands. So when the engine starts, you say a prayer: “Oh, thank you, God.”

When I was a young college student, I had a car that was so old I never knew when it would start and when it wouldn’t. And there were plenty of times it didn’t start. Your car is probably in better shape than that, but my point is this: the car starts due to laws of nature. Whose laws are those? The laws of nature are part of Īśvara’s intelligent order.

To have that constant appreciation of Īśvara’s intelligent order is one of the crucial aspects of this attitude of karma yoga. When the car starts, and you have that sense that this is part of Īśvara’s order—whether or not you reach home, by the way, is also part of Īśvara’s order. Whatever happens is part of Īśvara’s order.

But now we have a little more complexity here about “getting home.” You may not reach home if there is an accident. We have to stop and understand something about the doctrine of karma here. Yes, Īśvara is karma-phala-dātā—but of two kinds. This is an important topic, an important aspect of the doctrine of karma, and Śrī Krishna addresses it directly in the last quarter of this verse. We’ll see it in just a few minutes.

Before we go there, let’s go back to this pen example, to explain in very simple terms. When I drop the pen, I make an effort. (I’ll give you the Sanskrit words in just a moment.) I drop the pen—I make an effort. Now, is the result due to my effort alone, or are there other factors involved? This is where the doctrine of karma comes in.

There could be other factors involved. For example, if there were a strong wind blowing when I drop the pen, it may go the other way. Or—just to make up a bizarre example—suppose, as I drop the pen, there’s an earthquake, and physically everything moves to the side, so the pen moves to the side. Bizarre, I know, but you get the point. Other factors could interfere.

An earthquake or wind—maybe we’ll stay with the wind, it’s easier to understand. A strong wind is natural, right? Part of Īśvara’s natural order. Just as gravity is one force acting on the pen, wind is another force acting on it. But wind may be a factor we don’t anticipate. Gravity we can anticipate; wind we may not anticipate.

Now, there’s yet another hidden factor—in science they call them “hidden variables.” Hidden variables are present all the time without us even being aware of them. My guru loved this example of hidden variables. He gives the example of crossing the street to catch the bus.

He said there are four possible outcomes of that situation based on hidden variables. What are those four possible outcomes?

- You cross the street and you catch the bus. (Good—you get what you want.)

- You cross the street, and before you get on the bus, a friend of yours pulls up in a car and says, “Get in, I’ll give you a ride.” (You get more than what you want.)

- You cross the street, but the bus pulls away before you get on. (You get less than what you want.)

- You’re halfway across the street, something happens, and you wake up in a hospital bed. (The opposite of what you want.)

This demonstrates the fact that there are hidden variables in every situation, which prevent us from knowing in advance what will be the outcome.

So here, I’m giving the example of dropping the pen, and one possible hidden variable could be wind. Now, let me give you another very bizarre hidden variable. Suppose yesterday—I can’t think of a nice example, and this is not a nice example, but bear with me—suppose yesterday I did something very hurtful to someone, and that person is extremely hurt. Unfortunately, the person is also mentally ill. And suppose today that mentally ill person comes into the āśram, and as I’m about to drop the pen, that mentally ill person shoots me dead.

I apologize for the metaphor, but what a clear example of a hidden variable brought about by my own prior action. This brings us into another dimension of the doctrine of karma. My action yesterday—hurting that person emotionally—had a delayed consequence. These delayed consequences we understand as being part of the doctrine of karma.

The point I’m making here is that we perform an action, and the result of the action is based not merely on the laws of nature, but also on the laws of karma. This is the point. The outcome of any action is partially based on the laws of nature and partially based on the laws of karma. In both cases, the laws of nature are Īśvara’s laws, and the laws of karma are Īśvara’s laws. Therefore, Īśvara is the karma-phala-dātā. Īśvara gives you the result of your actions based on the laws of nature and the laws of karma.

I apologize for the example—I wish I had come up with a nicer one. That one was unpleasant.

Now, there’s more here. After giving in the first half the basic instruction, some further instructions come here to Arjuna:

“Mā karma-phala-hetur bhūḥ.”

Mā bhūḥ—don’t be. Don’t be what? Karma-phala-hetuḥ. Hetuḥ means cause, and in this case karma-phala-hetuḥ means karma-phala-dātā, giver of the results of action. Don’t think you are the hetuḥ, the cause for karma-phala. Don’t think you are the dātā, the giver of karma-phala.

This means: have the intelligence and humility to know that once you’ve committed an action, the results are not in your hands.

In conventional life, we talked about the illusion of competency. That illusion of competency is what Śrī Krishna is warning against here. Don’t think you are the god of your life, the master of your life. Yes, you are in control of your actions, your decisions—but that is where your control comes to an end.

Have the intelligence and humility to recognize that the results of any and all actions you commit are not in your hands. The results are in Īśvara’s hands.

And finally: Mā te saṅgo ’stu akarmaṇi.

We have to break the words apart here. Te—for you, Arjuna. Mā astu—may there not be. May there not be, for you, Arjuna, any saṅgaḥ—attachment. Attachment to what? Akarmaṇi—to inaction.

When you read this, the meaning may not come very clearly. What does it mean? It means: Arjuna, don’t think you are the god of your life, don’t think you are the karma-phala-dātā. Have the intelligence and humility to know that you are the author of your actions—you are not the author of the results.

Again, adhikāra doesn’t literally mean “author,” but that word gives the right sense. You are the author of your actions; you are not the author of the results.

Then he concludes: I say also, Arjuna, don’t be attached to inaction—don’t be drawn into passivity. Now, why is Śrī Krishna saying that? He is saying that because of a common misunderstanding of the doctrine of karma.

That common misunderstanding is: whatever is going to happen is in Īśvara’s hands. So, if whatever is going to happen is in Īśvara’s hands, then it doesn’t make any difference what I do—or whether I do anything at all.

Here’s the misinterpretation: “Why should I do anything? It’s all in Īśvara’s hands. It’s all in Īśvara’s hands.”

This is the misunderstanding of the doctrine of karma that Śrī Krishna wants to warn Arjuna—and all of us—against.

Look at this: if I drop the pen, there’s a result according to both the laws of nature and the laws of karma—both of which are Īśvara’s laws. But suppose I decide: “Why should I even bother dropping the pen? Whatever is going to happen is in Īśvara’s hands.” Well, if I don’t drop the pen, nothing happens.

If I drop the pen, I’m going to drop the pen—nothing happens without the initial action. The point is that there are two different factors involved here:

- My effort in making an action.

- Īśvara’s laws—in the form of the laws of nature and the laws of karma.

This is what we didn’t discuss earlier about the law of karma, and this is what we have to discuss right now.

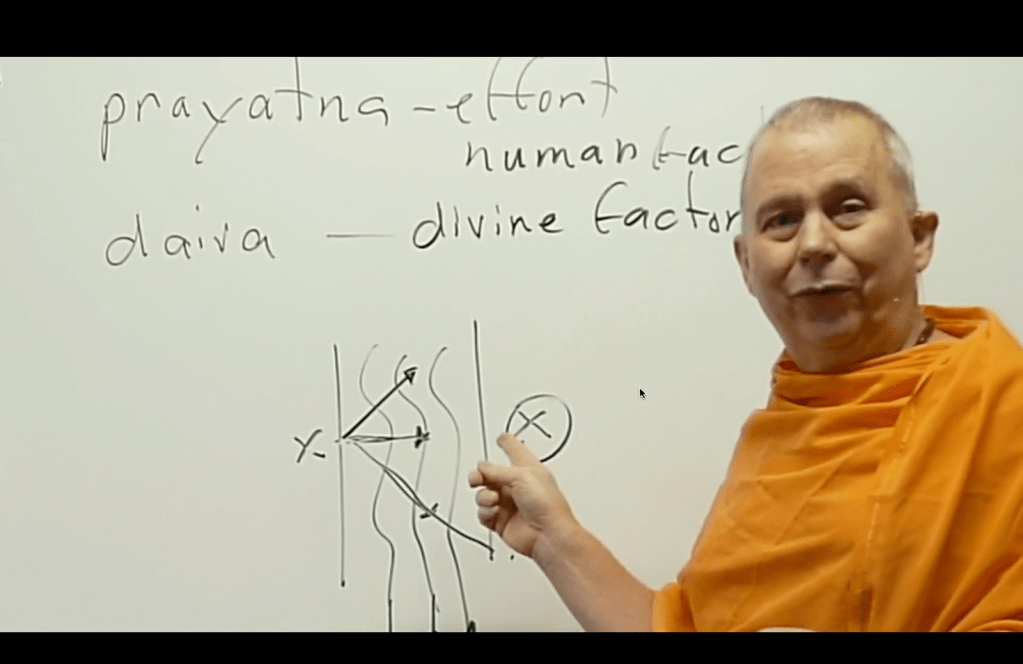

Let me go to the board—I can explain it a little bit more nicely.

The outcome of dropping the pen is partially due to me (I have to drop the pen) and partially due to Īśvara’s laws—just like for the surgeon.

The outcome of the surgery is partially due to the surgeon. If the surgeon is not skillful or not properly trained, there’s not going to be a good outcome at all. So the outcome of the surgery is partially in the surgeon’s hands and partially in Ishvara’s hands. Two factors: one factor that’s in our hands, and one factor that’s in Ishvara’s hands.

The words that are commonly used for these two factors are prayatna—effort—and daiva. Now, daiva is a little hard to translate into English. It means “that which comes from deva,” that which comes from God. I can’t think of a single English word that fully captures it, so we’ll call it “the divine factor.”

So, there’s a human factor (prayatna, effort) and there’s a divine factor (daiva, Ishvara’s presence in the form of the laws of nature and the laws of karma). The outcome is the result of both of these factors together. Both are always present in every single situation.

Let me share with you one of my favorite metaphors that describes how these two factors conspire together to give the result of an action. Suppose you come to a stream. You’re standing at the edge of the stream bed where the current is flowing from top to bottom. That’s the current. You want to swim to the other side of the stream—let’s call it a river.

So you jump into the river and start swimming toward your destination on the other side. But because of the current, you know very well you won’t go straight across. You’ll go diagonally.

By the way, those of you with a math background might remember something called vector addition or dot product—that’s what this is in mathematical terms. It shows how the result is due to two factors: your effort in swimming (prayatna) and the force of the current, which represents daiva—one of those hidden variables.

The current is a hidden variable because, when standing on the shore, you can’t tell how strong it is. The water you can see; the current you can’t necessarily see. But notice—the outcome is the result of both factors.

Now, look at what Shri Krishna said here: Ma te sangaha astu akarmani—“Don’t be attached to inaction.” What he’s warning against is the attitude of standing on the riverbank thinking, “Oh, there’s a current. That means I’m not in control of where I’ll end up, so why bother trying? Why not just sit here inactive?” That’s a mistake.

You already know it’s possible to reach your destination even with the current. For example, if the current takes you downstream, you can walk back up to where you wanted to go. Or, if you’re really smart, you’ll swim diagonally upstream, compensating for the current, and reach your goal exactly.

The fact that there’s a current doesn’t prevent you from reaching your goal—but you have to account for it and make adjustments accordingly.

Wouldn’t it be helpful to have a few moments of prayerful reflection if there’s a health crisis or an accident, to understand that the outcome of this situation was not in my hands in the first place? The outcome of this situation, in the case of a health crisis or an automobile accident, is due to forces of karma. Some bad karma from earlier in this life, or from a past life, is bearing fruit now in this situation—bringing about this health crisis, bringing about this automobile accident. Completely unanticipated, but occurring according to Ishvara’s intelligent order.

Health crises are part of Ishvara’s intelligent order. Automobile accidents are part of Ishvara’s intelligent order. All of this occurs according to Ishvara’s intelligence.

Suppose after the health crisis or accident we can compose ourselves and reflect on the fact that whatever is unfolding—whatever is happening—it’s all in Ishvara’s hands. With that reflection, instead of being driven by anxiety and confusion, you’d probably find yourself a little more composed and focused, and not so anxious.

With that moment of reflection, you’d be able to choose a much healthier response to the situation. So, instead of responding in a state of panic and confusion, you can respond with composure and clarity.

We’ve just begun. There’s so much more to discuss, both about the doctrine of karma, but even more so about the practice of karma yoga. We’ll see more in our next class.

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti. Om, Tat Sat. Thank you.