Gita Class 015, Ch. 2 Verses 42-46

Apr 18, 2021

YouTube Link: Bhagavad Gita Class by Swami Tadatmananda – Ch.2 Verses 42-46

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

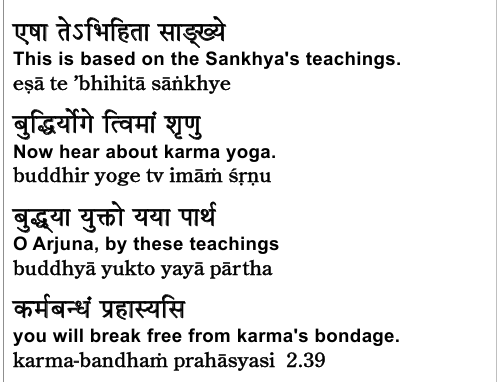

Good. Welcome back to our Weekly Bhagavad Gita class. We continue on our study of Chapter Two. We’ve just begun the topic of Karma Yoga. We’ll begin our recitation today with several verses beginning with verse 39. Please glance at the meaning while I’m chanting so that you can recite after me with the meaning.

We’ll stop there and pick up the thread.

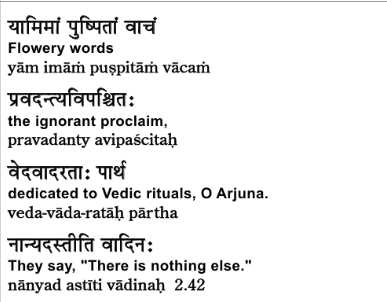

We finished—yeah, we finished verse 41. So we’ll begin with verse 42.

The context, as we discussed in the previous class, is where you have several verses here to introduce the topic of Karma Yoga. The topic of Karma Yoga actually begins with the famous verse 47. We’ll see that soon.

So these verses are introducing the topic of Karma Yoga. And, as I mentioned in the previous class, first Śrī Krishna wants to make sure we understand what Karma Yoga is not. And I mentioned in the prior class a common confusion with regard to the word karma—at least a common confusion in ancient times—when karma meant Vedic karma, Vedic rituals.

The word karma was frequently used in the sense of Vedic rituals in ancient times. And Śrī Krishna wants to make it really clear that Karma Yoga is not the performance of Vedic rituals. In fact, as you’ll see, he’s highly critical of the excessive focus on ritualism—the same complaint that many people have today about Hinduism. Śrī Krishna himself had the same complaint about Hinduism as commonly practiced many thousands of years ago, several thousands of years ago.

In this context, at the end of the last class, I made a differentiation between two sections of the Vedas. I want to remind you about that two fold division. We can divide the Vedas in several ways—there are four Vedas, each with their own name. But within each of the four Vedas, there are two broad sections (there are other ways of dividing them up as well).

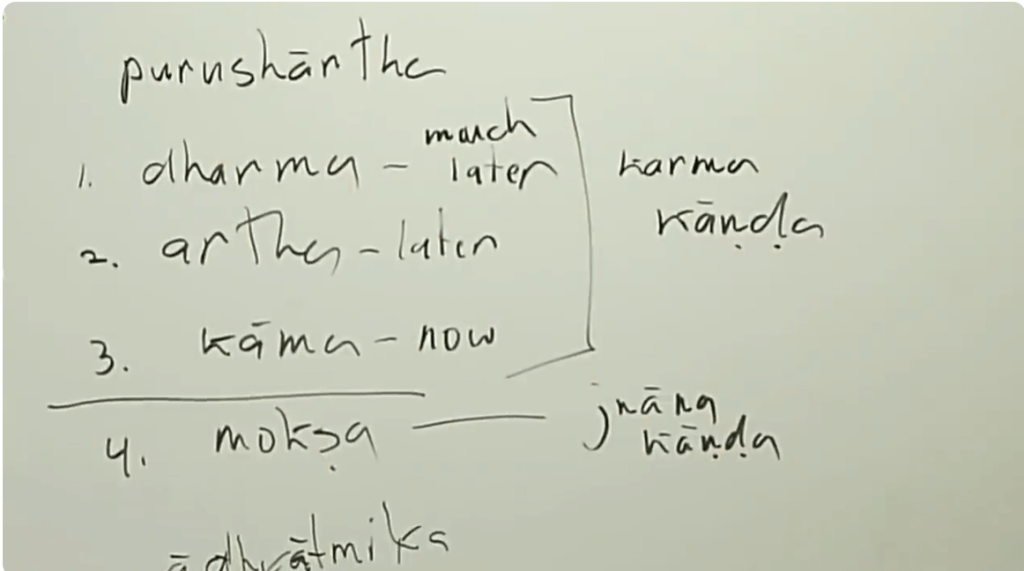

The two broad sections are Karma Kāṇḍa and Jñāna Kāṇḍa. Kāṇḍa means part or portion. Karma Kāṇḍa is the portion of the Vedas devoted to karma—remember, karma here means rituals. And then, at the end of each Veda, is a small part which is the Jñāna Kāṇḍa—the part of the Veda devoted to jñāna, spiritual wisdom. Because those portions occur at the end of each Veda, they are called Vedānta—Veda + anta.

So we talked about that in the prior class. Here, Śrī Krishna is going to criticize those who are excessively focused on the Karma Kāṇḍa of the Vedas—those who ignore the Jñāna Kāṇḍa of the Vedas.

And before we proceed, one point—I’m not sure if I made it clearly in the last class—it’s an important point. The performance of Vedic rituals was done for the sake of specific goals. In fact, we did talk about the first three of the four Puruṣārthas: gaining kāma (pleasure now), gaining artha (wealth, so that you can enjoy pleasure for the remainder of this life—pleasure or contentment), and then dharma (accumulating religious merit, so that you could enjoy pleasure and contentment in whatever state follows this life).

The point I want to make before we plunge in here is that the performance of Vedic rituals was for the sake of that pleasure and contentment—pleasure and contentment now, later, and in the next life. The purpose of those Vedic rituals was dharma, artha, and kāma—the first three of the four Puruṣārthas.

The Jñāna Kāṇḍa is for the sake of mokṣa, the fourth of those Puruṣārthas. If you’re not familiar with this topic of the four Puruṣārthas, we discussed it at the end of the prior class—you can go back and listen to that.

So with that in mind, here’s Shri Krishna—Shri Krishna is critical of those who focus on the Karma Kāṇḍa, seeking pleasure and contentment, and those who overlook the Jñāna Kāṇḍa, which leads you to discover the true source of pleasure and contentment within.

We’ll have all that discussion. So that’s a reason:

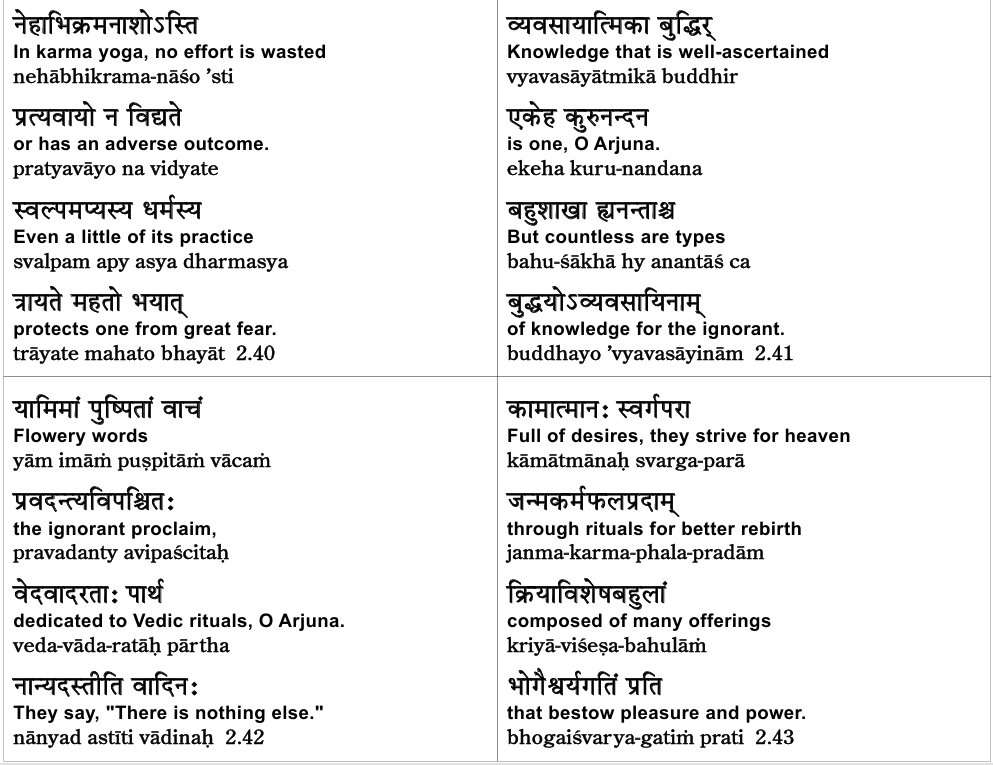

Good. Excuse me—starting the third line, Pārtha O! Arjuna is addressed by Śrī Krishna. Śrī Krishna says—he’s talking about those who are vedavāda-ratāḥ, those who revel vāda, the teaching of the Veda, and specifically in the Karma Kāṇḍa of the Veda.

That’s the context—you see it very clearly. So he’s criticizing those who revel in the Karma Kāṇḍa of the Veda. He calls them, in the second line end, avipaścitaḥ—they’re not clear of thinking. They haven’t clearly discerned that the ultimate source of contentment and pleasure is within. And so, since they haven’t discerned the true source within, they’re focused out in the world, gaining happiness, contentment, peace, and joy through worldly activities—through worldly pursuits—supported by the performance of Vedic rituals.

Vedic rituals are done to help you gain worldly goals. Let me say that again: Vedic rituals were done to help you gain worldly goals—dharma, artha, and kāma. So Śrī Krishna criticizes them. Those who are committed to the karma kāṇḍa of the Veda, they are avipaścita—they haven’t properly discerned what’s really going on. They haven’t properly discerned the true source of contentment within.

And because they’re ignorant—pravadaṃti, in the beginning of the second line—they say, they utter vācam in the first line. They utter imam vācam. These words, the imam—yām imam vācam—they utter such words that come from the Vedas, which Śrī Krishna here calls puṣpitāṃ vācam—flowery words.

Flowery words in the sense of very appealing words of the Vedas. So, since the karma kāṇḍa says that by doing these rituals, you can go to heaven, you can attain… you can get the birth of a son, you can acquire wealth—these various worldly goals available through Vedic rituals—Śrī Krishna calls all that puṣpitāṃ vācam, flowery words, and has them criticized.

Those who are committed to the vedavāda, to the karma kāṇḍa, he concludes—not concludes—he says further in the fourth line: na anyat asti iti vādinah. He says they are vādinah—they’re people who say… People who say what? Na anyat asti—it’s like a closed quote. Na anyat asti—there is nothing else. There is no other way—you know, paraphrasing now—there is no other way to gain contentment, joy, happiness, peace, love. There is no other way to gain these except through the performance of Vedic rituals. And this is what Śrī Krishna is highly critical of.

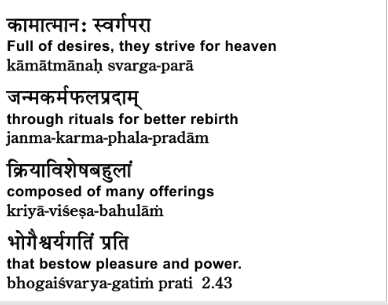

And he continues: kāmātmānaḥ svargaparā. So still speaking about those who are committed to the karma kāṇḍa of the Vedas—those who are committed to this highly ritualistic form of the practice of Hinduism—he calls them in the next verse kāmātmānaḥ.

Here, ātma means heart or mind. Ātma doesn’t always mean sat-cit-ānanda ātmā, your true self. Ātma can simply mean yourself—here it means mind. Kāmātmānaḥ—those whose minds are filled with kāma, desire. What do they desire? They desire pleasure now—kāma. They desire pleasure for the rest of their lives—artha. And they desire pleasure in whatever follows this life—dharma, the first three of the four puruṣārthas.

And they are svarga-parāḥ. They are parā—focused on svarga, getting to heaven. Their ultimate goal is to get to heaven. They realize perhaps that the pleasure they can enjoy in this life is limited—as a human being, there is only so much pleasure you can enjoy, and there is a lot of suffering associated with a human birth. So they are focused on going to heaven and having a deva śarīra, having a godly body, which is not going to be subject to suffering at all.

So, in heaven, they can have pleasure with no suffering. So, we’ll be able to take a reference to that in the final line—we’ll get there. Oh—in the final line, pick up that word prati. We need that word prati. They are—towards, they are focused on—what are they focused on? In the second line, they’re focused on janma-karma-phala-pradām—the rituals which are pradām, the rituals which give karma-phala, the fruits of one’s actions. And here the karma specifically is ritual—karma-phala is the result of Vedic rituals. And actually, a better way of interpreting this: the phala—and my translation here is helpful—so, they want the phala of doing the rituals. And the phala of doing those rituals is twofold here: janma—a better birth, specifically a birth in heaven—and karma, puṇya karma, religious merit.

So they are prati—they are focused on these rituals which bestow good karma and better rebirth. And those rituals are kriyā-viśeṣa-bahulām. Those rituals are bahulām—they’re filled with viśeṣa, many specific kriyā—kriyā meaning actions. There are many steps in those rituals. Many parts. If you’ve watched a skilled Hindu priest performing a homa or a havan, a fire ritual, you see there are so many steps involved—kriyā-viśeṣa-bahulām. Those rituals are filled with so many steps and parts to the rituals.

And they are prati—they’re focused on bhoga-aiśvarya-gatim. They’re focused on a gati, a goal. The goal was heaven. And the goal of heaven is a condition in which there is bhoga—pleasure—and aiśvarya—power, sovereignty, absence of suffering.

So they’re focused on getting to heaven as opposed to being focused on mokṣa. Mokṣa is reached through the force of those four puruṣārthas we discussed in the last class—I’ll put them back up on the board a little later when we get to that part.

Continuing—he’s not done with this criticism of rituals:

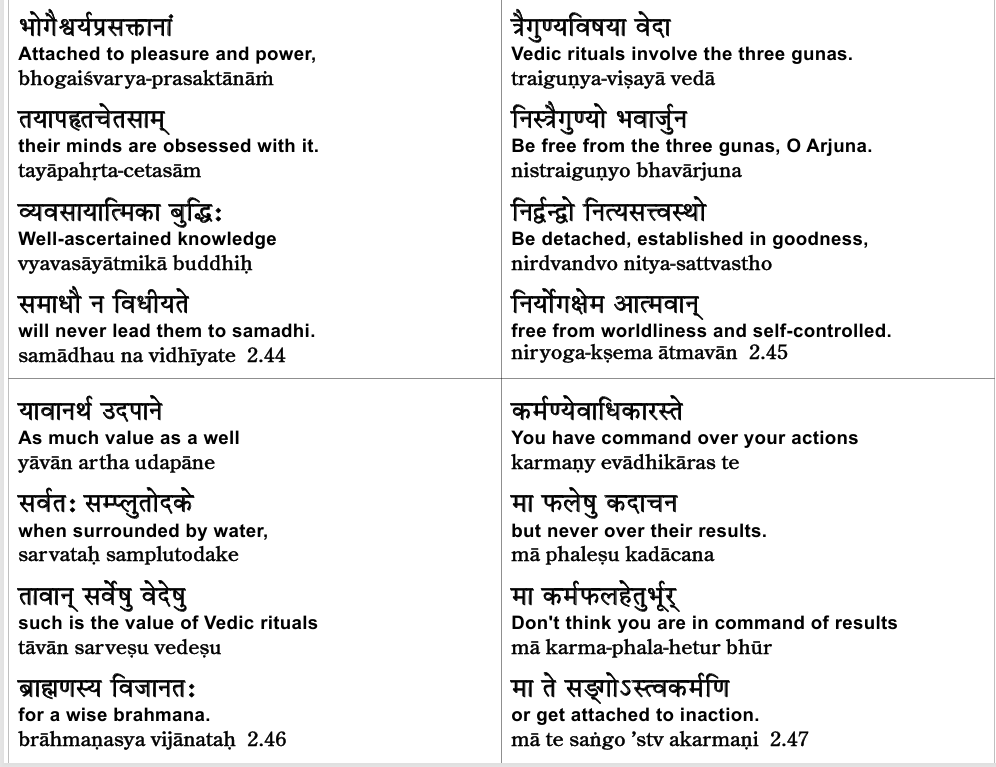

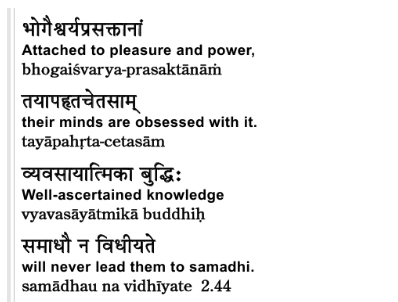

So the prior verse talked about bhoga—bhoga-aiśvarya-gatim prati—those focused on bhoga, pleasure, and aiśvarya, power. So he’s referring to those—bhoga-aiśvarya-prasaktānām—for those who are prasaktā, attached to, dedicated to… Dedicated to what? Bhoga and aiśvarya—pleasure and power—which you gain by performing rituals and going to heaven.

So, about those, he says: tāyā-apahṛta-cetasām. Tāyā—by their attachment, or by their ignorance—they are apahṛta-cetasām. Their cetas, their minds, are apahṛta, carried away. Their minds are carried away by their attachment to power and pleasure. Does that sound a little familiar? This is the human condition—so many people are riveted—apahṛta-cetas, one whose mind is carried, literally, carried away. Those whose minds are carried away by their attachment to power and pleasure.

What about them? Śrī Krishna says for them: vyavasāyātmikā-buddhiḥ na—the na at the end of the last line. So vyavasāyātmikā-buddhiḥ—here buddhiḥ means an understanding which is vyavasāyātmikā, which is well-ascertained. And we saw that expression in verse 41—right here, first line: vyavasāyātmikā-buddhiḥ or samāyātmikā—the buddhi, an understanding which is vyavasāyātmikā.

We had a long discussion when we saw verse 41—in fact, it was a discussion of the four puruṣārthas. So we said vyavasāyātmikā-buddhiḥ, the well-ascertained understanding, is the ascertainment—let me get the slide back—is the ascertainment that the pursuit of dharma, artha, and kāma can never lead you to complete peace and uninterrupted contentment? I should have talked about this before. Let me mention it right now.

Anything you achieve through kāma—effort—whether it’s a worldly effort, like going to work in the morning, or whether it’s a ritual effort to do complicated rituals, the results of any karma, any worldly karma or any religious karma, will always be limited—finite. So, it means if you work really hard, you get a paycheck, but the paycheck is a finite amount. If you do lots of rituals, you collect religious merit, but the religious merit is a finite amount. With that finite paycheck, you can only buy a finite number of things. With that finite religious merit, you can perhaps go to heaven, but as many of you know, the Hindu concept of heaven is that when you exhaust all your religious merit, you get reborn again into another life.So, the result of any karma—whether it be a worldly karma or a religious karma—is finite; it’s limited. And the problem is, we want perfect peace. We want perfect contentment.

A story I made up, I’ve told many times, I’ll tell it right now—it fits in. I jokingly invented a pill. Suppose some scientist develops a pill: you take this medication, and you will be happy 99% of the time. By taking this medication, you will be happy 99% of the time. Suppose I have that pill. Will you take it?

Well, that would be a reasonable thing to do, because being happy 99% of the time is not bad—better than what you normally experience. But suppose the next time I see you is the 1% of the time when the medication doesn’t make you happy. And I see you so miserable, and I ask you, “What happened? I thought you took the pill.” And you said, “Yeah, 99% of the time I’m happy. Right now, I’m miserable.”

And here’s the point: can you accept being miserable 1% of the time when you’re happy 99% of the time? Well, while you’re in that 1% of misery, you can’t accept it at all. We want perfect peace, perfect contentment, uninterrupted contentment. And that state of perfection cannot be accomplished through finite karmas. So, finite worldly actions will not lead you to a state of perfect contentment and peace. And the finite rituals you do will never lead you to perfect peace and contentment.

On the other hand, shifting your attention away from Dharma, Arta, and Kāma—shifting your attention towards the fourth Puruṣārtha, Mokṣa—you are now seeking the true source of contentment and peace. And when you have found that true source of contentment and peace, you will, in fact, enjoy perfect, unbroken, uninterrupted contentment and peace.

The vyavasāyātmikā buddhi is that discernment—the discernment of the fact that the pursuit of Dharma, Arta, and Kāma, through any amount of effort, worldly effort or religious effort, cannot possibly gain you perfect, complete contentment and peace. It can only be achieved through seeking Mokṣa—liberation, enlightenment.

That discernment is vyavasāyātmikā buddhi, and here in this verse, Śrī Krishna says: for those who are attached to pleasure and power, for those whose minds are overcome by their attachment to pleasure and power, for them, vyavasāyātmikā buddhi—this discernment of the limitation of what you can achieve through effort and the recognition of what you can gain by gaining Mokṣa—for those people who are carried away by their attachment to pleasure and power, this discernment, na vidhi-yate, it will not arise in their minds.

This discernment is like a transformation of priorities in life. Generally, you have a to-do list—many things you have to do—and maybe you prioritize your to-do list. So, there are so many things to be done in life. Vyavasāyātmikā buddhi is the discernment where Mokṣa, spiritual growth, is the number one goal. In your to-do list, it’s number one. Other things also have to be done, and you’ll continue to do all of those. But when seeking Mokṣa is in the number one position on your to-do list, that is the proper discernment—vyavasāyātmikā buddhi.

But for these people who are committed to Vedic rituals and going to heaven, that discernment—na vidhi-yate—it will not arise for them.

Samāddhau. My translation here—maybe it’s not in keeping with the commentary of Madhusūdana Sarasvatī, which I referred to when I prepared for class. So you can say, “will never lead to samādhi“—it’s correct and it’s meaningful. But Madhusūdana—samādhi, as you know, is a state of meditative absorption, which is the common meaning of samādhi—but Madhusūdana Sarasvatī, in his commentary, goes to the root meaning of samādhi. You can break down the word into the root dhā—”to place”—with the prefixes sam and ā: sam-ā-dhā, “to place well.” Samādhi is, in one sense, a well-placed mind. In a meditative sense, you can kind of see how it gets that meaning. So, a well-placed mind is a mind established in the absorption of samādhi. But the meaning Madhusūdana takes here is samādhi—a mind which is well-placed, well-placed in truth, well-placed in Brahman. This is how Madhusūdana takes it. He wouldn’t like my translation, but there are several ways—I should mention—there are several commentaries on the Bhagavad Gītā, and they will interpret that word samādhi differently translate it as I did here. In the absence of—if you are focused on doing Vedic rituals to go to heaven—you’re not going to gain samādhi and gain enlightenment. Or, in the sense of Madhusūdana’s commentary, if you are focused on rituals, you will never gain the discernment and gain that enlightenment in which your mind is established in truth, established in Brahman.

Okay, next:

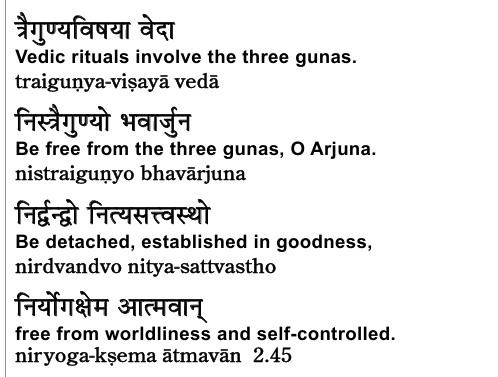

Traiguṇya-viṣayā vedā—the Veda. For “Vedas,” and remember, in context, he’s referring specifically to the karma-kāṇḍa of those three Vedas, the portion of the Vedas focused on ritual. He says, those Vedas are traiguṇya-viṣayā—the subject matter (viṣaya) of those Vedas is traiguṇya. You know of the three guṇas. The three guṇas are the pre-scientific way of understanding the world. In modern science, we understand the world in terms of matter and energy. In ancient times, they understood the world in terms of sattva, rajas, and tamas. So, we can refer to the world as matter and energy, or we can refer to the world in terms of the three guṇas—sattva, rajas, and tamas. So traiguṇya means “worldly,” that which is composed of sattva, rajas, and tamas—the three guṇas. Traiguṇya-viṣayā vedā—Śrī Krishna says, “The Vedas have, as a subject matter, that which is traiguṇya, that which is worldly.”

I’m smiling because there’s nothing fundamentally spiritual about the performance of Vedic rituals.

Now, understand first of all the word “spiritual.” Spiritual is a translation of the Sanskrit word adhyātmika—that which is focused on the true self, that which is focused on reality, that which is focused on gaining enlightenment.

But Vedic rituals, as we saw before, are focused on gaining… The Vedic rituals are for the sake of dharma, artha, and kāma. These three—let me get them up on the board, because we’re going to need them later anyway.

I keep referring to these four puruṣārthas. We discussed them in a prior class, and I want to return to that now.

The term puruṣārtha—the artha, the goal of a puruṣa (person). There are four: dharma, artha, kāma, and mokṣa. And we’ve discussed this at length in a prior class, but just to return to this really important teaching:

We said that kāma is for the sake of contentment now. Kāma means pleasure. Artha is gaining wealth—wealth which is necessary to enjoy contentment later in this life. And then dharma is the accumulation of religious merit, so that whatever follows this life would be a condition of contentment—so we’ll jokingly call that “much later.”

But notice: contentment and pleasure now, contentment and pleasure later, contentment and pleasure much later—how worldly is that? There’s nothing spiritual about it. There is something religious about it, because prayer is involved all the way through.

We distinguished between religion and spirituality. Religion is prayer and deals with matters of belief. Spirituality—as we use the word in Advaita Vedānta (it’s used differently in other places)—in Advaita Vedānta we refer to spirituality as, literally, the translation of the word adhyātmika.

Sorry for the long Sanskrit word here. Adhyātmika literally means “spiritual.” You can see the word ātma inside—focused on ātma. Adhyātmika means “focused on ātma,” pursuing truth, and pursuing truth adhyātmika—within yourself.

So here we can distinguish between an outward-turned pursuit and an inward-turned pursuit. This worldly pursuit—traiguṇya-viṣaya, that which is concerned with the world—is an outward-turned pursuit, and that is the pursuit of dharma, artha, and kāma, as opposed to an inward-turned pursuit, which is the pursuit of absolute truth, which is the pursuit of mokṣa.

This is the key distinction in that vyavasāyātmikā buddhi—that discernment. That discernment is a radical shift of orientation, where your orientation shifts away from that which is external—in our verse, called traiguṇya (“worldly”)—and the shift is from the worldly to mokṣa, that which is otherworldly, that which transcends the world.

We’ll come back to this in just a while. Let me just make one more comment or one more connection that we discussed before. We said that the first three of these puruṣārthas are gained by following the karma-kāṇḍa of the Veda, as opposed to mokṣa, which is gained by following—so I’ll just last recall—by following the jñāna-kāṇḍa of the Veda.

Okay, this is extremely important material.

Am I back? Good. So now, Śrī Krishna begins by saying traiguṇya-viṣayā vedā. Here veda means the karma-kāṇḍa of the Veda, and as we just saw, the karma-kāṇḍa of the Veda has as its subject matter that which is traiguṇya—worldly. The pursuit of dharma, artha, and kāma is a worldly pursuit.

And then comes the very powerful direction to Arjuna in the third line. He addresses Arjuna by name—“Arjuna” or “Arjuna, nistraiguṇya bhava.” Bhava—you should be nistraiguṇya, free from the three guṇas—literally “free from the three guṇas,” but contextually, “free from worldliness,” free from the pursuit of dharma, artha, and kāma. And you should be free from that and, obviously, focused on mokṣa—this is the censure.

Traiguṇya-viṣayā vedā—the karma-kāṇḍa of the Veda—is concerned with worldly matters. So therefore, Arjuna, nistraiguṇya bhava—“O Arjuna, you should be free from worldly matters,” meaning you should reject the karma-kāṇḍa of the Veda. This is a very powerful rejection of the excessive ritualism of ancient times, some of which persists even to this day.

He continues to tell Arjuna that: “Arjuna, bhava—you should be nirdvandvaḥ—free from these dualities.” And here Dvandva means a “pair.” And a pair—these are generally called “pairs of opposites.” So you’ve got pleasure and pain, cold and heat—these opposites where you seek one and want to avoid the other. You seek pleasure, you want to avoid pain. That’s kind of the basic rule of life.

But if you remember, I think in the last class we discussed how the problem is one of compulsivity. We need to return to this—won’t make any sense unless we’ve returned to that teaching we discussed before—about the difference between likes and dislikes, and binding likes and dislikes—rāga and dveṣa.

We’ve said in a prior class that having likes and dislikes is normal. When he says nirdvandvaḥ—“be free from these likes and dislikes”—it doesn’t mean “anything is okay.” That’s unnatural. I gave the example that my own guru prefers coffee over tea. Having been born in South India, he grew up drinking coffee. He also drank tea, but he had a preference for coffee.

The point is, having likes and dislikes is normal—it is not the problem. The problem is when you get compulsive about it—where you have to get what you like and you have to avoid what you dislike. The problem is not likes and dislikes. The problem is being emotionally compelled to seek what you like and being compelled to avoid what you don’t like. The problem is compulsivity.

And when he says nirdvandvaḥ bhava o Arjuna—“you should be free from these pairs”—you should be impartial, as a literal translation. You should be free from these pairs. The context is: you should be free from this compulsivity. You should be nitya-sattva-sthaḥ—you should be always established in sattva, a state of purity. What he is referring to here is a state of mind in which you can break free from pursuing dharma, artha, and kāma, and instead pursue mokṣa.

The problem is a problem that is well known to you, and that is: we only have so much time available in each day. And if 100% of our time is engaged in dharma, artha, and kāma, how much time is available for seeking mokṣa? That is a problem. So the instruction to Arjuna—nistraiguṇya—turn your back on seeking these worldly goals (dharma, artha, and kāma). And “turn your back” means not to ignore them completely, because you have to live in the world—unless you become a saṃnyāsī, a Hindu monk, and live in an āśrama or a cave. You have to be involved in worldly activities, but as I said before, the trick is to make mokṣa the number one priority. And that is the message being given to Arjuna here.

Nirdvandva—break free of this conventional worldly pursuit of chasing after what you want and running away from what you don’t want.

Nitya-sattva-sthaḥ—always be established in a state of mental purity where your mind is available to pursue mokṣa.

Nir-yoga-kṣema—be free from… There is a common expression yoga and kṣema. Here, yoga has nothing to do with what you commonly understand as “yoga.” In this expression, yoga means getting what you want, and kṣema means preserving what you’ve attained. Yoga is a state of getting what you want; kṣema is a state of preserving it.

Yoga is getting the cup of tea; kṣema is not spilling it so that you can enjoy it. So life is characterized as yoga and kṣema—acquisition of what you want, and kṣema, protection or preservation of what you’ve gained.

And here, Śrī Krishna says: break free from that. Break free from this conventional worldly attitude so that you can focus on gaining mokṣa. And he ends the sentence by saying: you should be ātmavān.

Ātmavān—literally “possessed of ātma.” What does that mean? I said before, who is not possessed of ātma? Everyone has ātma. Ātma here doesn’t mean sat-cit-ānanda. Here, ātma simply means “self.” Ātmavān means “self-possessed.” And in our context, we could say “being internally focused.”

We distinguished between being externally focused in the pursuit of dharma, artha, and kāma—externally focused in the pursuit of those worldly goals—as opposed to being internally focused for the sake of gaining mokṣa. That condition of being internally focused is called here ātmavān—literally “self-possessed.”

Now, to introduce the next verse, let’s just get the context here. Suppose you have—let me introduce it properly—suppose you have undergone this transformation of priorities and intent, so that you’re no longer focused exclusively on pursuing dharma, artha, and kāma, and your primary focus in life is mokṣa. Let’s see—vyavasāyātmikā buddhi, as a discernment we discussed before. Suppose you have gained that discernment. Having gained that discernment, what would be your perspective on all these Vedic rituals? Here, Śrī Krishna is concluding his criticism of all those Vedic rituals. For one who has made this—where am I? Here—yes, to come back…

For one who has made that shift of intent—that shifting of one’s goal, shifting one’s orientation from that external orientation to the internal orientation, from that external worldly orientation to this internal spiritual orientation—for such a person who has made that discernment, what would be their attitude towards Vedic rituals?

And that’s what Śrī Krishna describes quite wonderfully in this next verse.

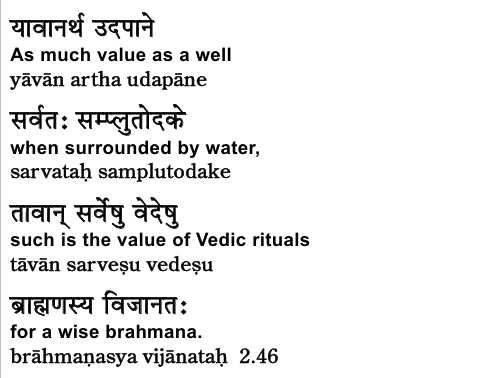

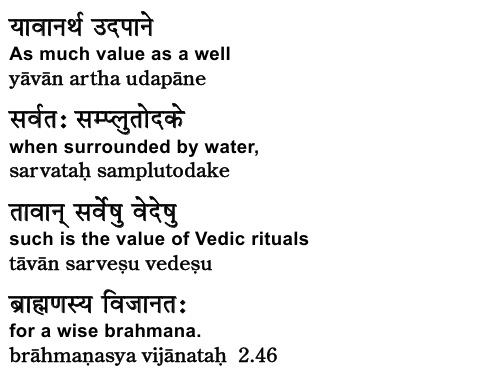

Vijanatha – one who understands properly Brahmanasya – One who pursues Brahman. For one who has properly discerned the worldly pursuit vs moksha

Yāvān arthaḥ udapāne—yāvān, “as much”; arthaḥ, “value.” Udapāne—a well, a source of water.

A well which is sarvataḥ, “on all sides,” sampluta-udake—udaka means water—so sampluta-udake means “surrounded by water.”

Here we need to understand the metaphor. In dry parts of India and other places, it’s not uncommon for villagers to dig a well in a dry streambed. The reason you might dig a well in a dry streambed is because a streambed means water, so you might presume that the water would be closer to the surface in that dry streambed.

So imagine villagers dig a well in that dry streambed, and they have access to water. That is their udapāna. Their well is in that dry streambed.

But then suppose, when the rains come—in July and August, September—the heavy rains come, and the rains are so much that the dry streambed is no longer dry. It’s now running with water.

Now picture it—the villagers built that well in the middle of that dry streambed, but now the well is surrounded by water all over the place. Śrī Krishna uses this metaphor: What is the use of that well when the well is surrounded by water? You don’t need to go to the well—you just go to the stream and you get as much water as you want.

So the point is that the well becomes superfluous. The well is no longer necessary.

This is what Śrī Krishna is teaching here. He says: yāvān arthaḥ udapāne, “as much value as one has for a well which is sarvataḥ sampluta-udake,” for that well which is surrounded all over by water, for that well in the streambed when the stream is flowing with water—tāvān, so that you recognize that the well is superfluous.

That is the value of the well. Yāvān arthaḥ—the value of the well—is that the well is superfluous. Tāvān, that much is the value sarveṣu vedeṣu—in all the Vedas. And again, he is specifically referring to the karma-kāṇḍa of the Veda.

Just as the well becomes superfluous when the rains come, in the same way the performance of Vedic rituals becomes superfluous, and the teachings of the karma-kāṇḍa become superfluous for one who has undergone that shift of orientation—when you have that vyavasāyātmikā buddhi, when you have that discernment that the pursuit of limited worldly goals is not worth it.

It’s not worth the effort. With that discernment, you turn your orientation away from worldly pursuits—you turn your orientation within.

Brāhmaṇasya vijānataḥ—for one who understands properly. Brāhmaṇa here doesn’t necessarily mean one who belongs to that caste, but rather one who is pursuing brahman. Another meaning of brāhmaṇa—often used in Vedānta—is one who pursues brahman, absolute reality.

So brāhmaṇasya vijānataḥ, for that one who has the proper discernment, for one who has discerned the limitation of worldly pursuits, for one who has shifted the orientation away from external pursuits and towards internal pursuit of truth—for such a person, just as the well surrounded by water is superfluous, in the same way, the ritualism taught in the Vedas becomes superfluous, having made that shift of orientation.

And we’ll end our class now, but I just want to show you the verse with which we’ll begin our next class—karmaṇy-evādhikāras te. With this verse, Śrī Krishna begins to teach what Karma Yoga is. So far, he’s been teaching what it is not, and he’s been teaching the shift of orientation, which is the basis for Karma Yoga. I’ll explain that in the next class, and we’ll see this very important verse.

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti. Om, Tat Sat. Thank you.