Gita Class 014, Ch. 2 Verses 37-41

Apr 10, 2021

YouTube Link: Bhagavad Gita Class by Swami Tadatmananda – Ch.2 Verses 37 – 41

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ.

Good. Welcome to our weekly class on Bhagavad Gita. We continue today in chapter two. We’ll begin, as always, with some recitation. Be sure to glance at the meaning while I’m reciting, then repeat after me.

Very good.

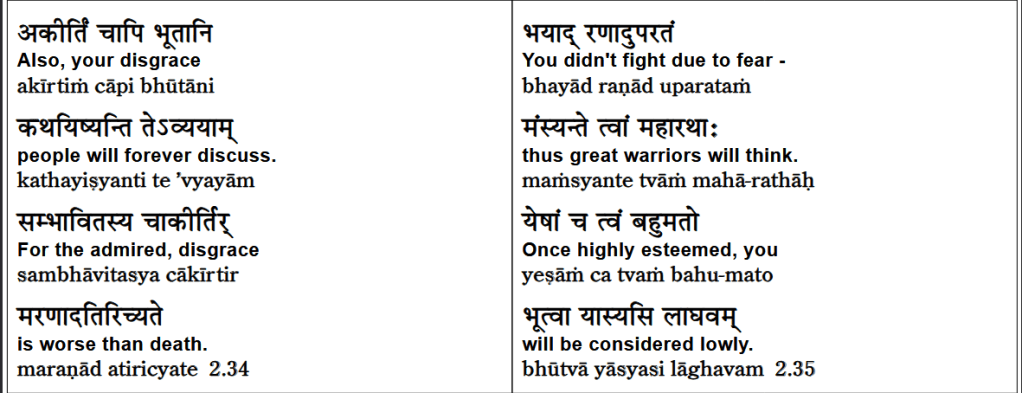

Let’s return to where we left off. We finished verse 36. We’ll continue with verse 37.

Just to set the context: here in chapter 2, way back in verse 11, Sri Krishna told Arjuna, “Arjuna, you’re grieving unnecessarily. You’re grieving for those who do not deserve grief.” Why? He proceeded then to give three different reasons.

Sri Krishna said, first of all, that when your beloved family members die on a battlefield, nothing will happen to Atma. Reason 1.

Reason 2 is that the Sukshma Sharira, the reincarnating entity, will travel on after they fall on the battlefield and take another life.

And reason number 3, which we’re discussing now—and that is that it is Arjuna’s duty and responsibility to fight. It is his Dharma. If he fulfills Dharma, he will be praised by everyone. And if he fails to perform his Dharma, he’ll be heavily criticized. We just saw that topic.

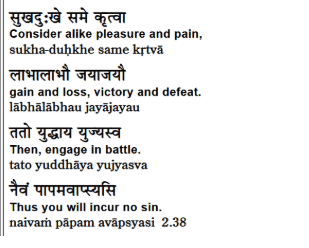

Hato va – If you are killed in the battlefield, prapsyasi – you will gain, Svargam – Swarga

And Sri Krishna gives further reasons that Arjuna should stay on the battlefield and fight to fulfill his Dharma, because—another reason in verse 37—you are engaged in a Dharma, you are in a righteous war. By fighting, you actually accumulate good karmas and avoid bad karmas. And as a result of which, if you happen to die in the battlefield (he doesn’t, but if he were to die in the battlefield), Arjuna would then go on to heaven after this lifetime.

Jitvā vā—the second possibility. First possibility is Arjuna might die in the battlefield. Second possibility, of course, is he might be victorious.

Jitvā vā—if you are victorious—bhokṣyase—you will enjoy mahīm, the world, referring to the kingdom. You’ll enjoy the fruits of this battle, which is regaining the kingdom that was unjustly taken away from the Pandavas.

So in either case—in American English, they say it’s “win-win.” If he dies, he wins heaven. If he conquers the enemy, he wins the kingdom.

Tasmāt—therefore, Kaunteya, O son of Kunti, Arjuna, therefore uttiṣṭha—get up. I think maybe about a half a dozen times in different places—and maybe in different ways—Sri Krishna says these same words: Tasmāt uttiṣṭha, uttiṣṭha Kaunteya—get up, get up Arjuna and fight. Because that’s the big picture of the whole Bhagavad Gita. The Bhagavad Gita, in the most simplistic way, is Sri Krishna encouraging Arjuna to get up and fight the war.

So—get up—uttiṣṭha Kaunteya, yuddhāya kṛta-niścayaḥ. Kṛta-niścayaḥ means being resolved, being clear and committed—yuddhāya—to fighting the war, to entering into battle.

Alright.

Then, by the way, one more verse will then conclude this current topic. Let’s see the verse and then we’ll wrap this section up.

Mention before it—so “win-win” situation for Arjuna. Therefore, this final bit of advice from Sri Krishna is:

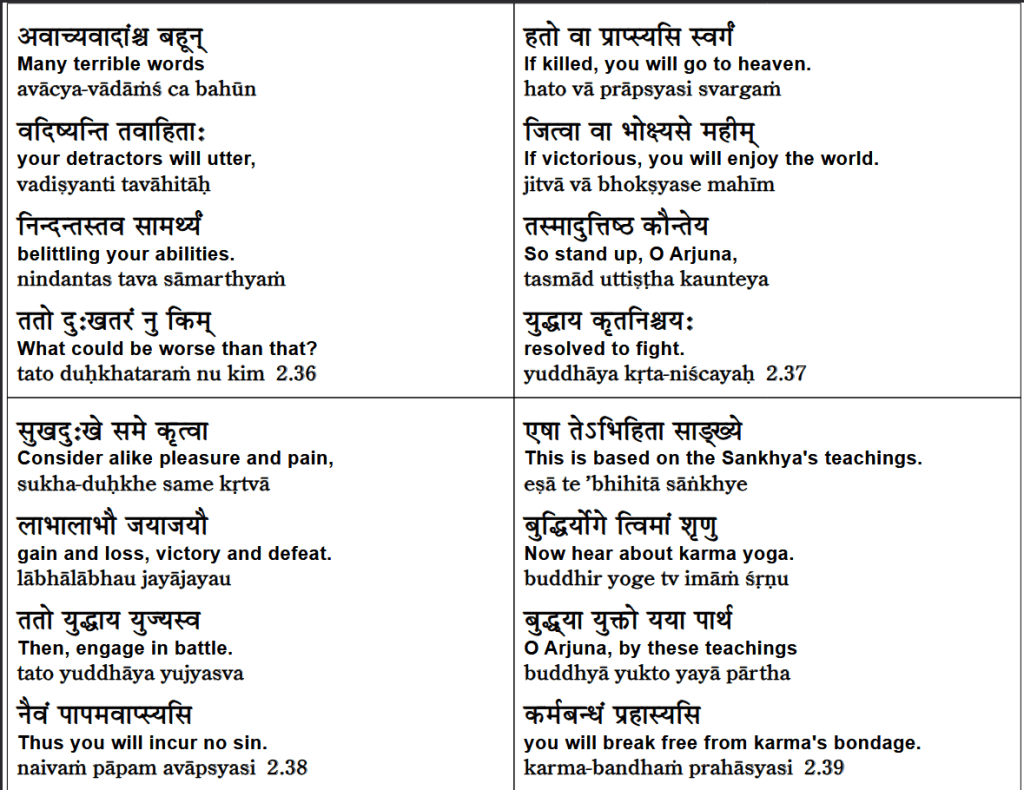

Sukha-duḥkhe sama kṛtvā—having made sama, the same—having made what the same? Sukha, pleasure, and duḥkha, pain, suffering. Making pleasure and suffering alike.

Lābha alābha—you know that “-āla” ending is a dual ending. Lābha and alābha. So, making gain and loss—lābha, gain, and alābha, the opposite of gain, loss—making them sama-kṛtvā, making them alike.

Jaya ajaya—making victory and defeat the same, treating them as the same. If it’s a win-win situation, then what difference does it make?

If Arjuna experiences sukha and duḥkha, which are inevitable in life, if Arjuna gains the kingdom or loses the kingdom, if Arjuna is victorious or if he’s not victorious—in either case, Arjuna is blessed. Blessed by either going to heaven or by regaining the kingdom.

Tataḥ—thereafter, after treating pleasure and pain, after treating gain and loss, after treating victory and defeat, after treating them all the same—gaining the big picture, standing back to understand the overall consequences of the situation.

Tataḥ—then, thereafter, yuddhāya—battle yujyasva. You yujyasva—engage yourself, yujya, in this battle. Go into battle. Engage yourself in this battle.

Evam—thus, na pāpam avāpsyasi—na pāpam avāpsyasi, you will not incur sin. Generally, in a battle—generally, when you kill someone—you incur a pāpa, sin. But because this is a Dharma Yuddha, as we discussed before—a Dharma Yuddha, a righteous war—being a war in which the consequences of not fighting are worse than the consequences of fighting.

So in this particular situation, by killing his enemies, Arjuna will not incur sin. In fact, it is the other way around—if he does not fight, he will incur sin. As we have said, because it is his Dharma, his responsibility.

And that concludes this whole opening section of chapter 2. Chapter 2 is unique in that it contains several subject matters—it is very long. Most of the 18 chapters of the Bhagavad Gita contain one subject, but chapter 2 is unique in that it contains several different topics.

So now we move on to the next topic. The next topic is Karma Yoga. And by the way, the topic of Karma Yoga is hinted at in this verse—sukha-duḥkha sama-kṛtvā, treating pleasure and pain alike—it hints at Karma Yoga. And we’ll explain that in quite a bit of detail as we go ahead.

Karma Yoga is a very important practice, a much discussed practice, and a much misunderstood practice. After we go through this topic, you’ll really understand very clearly what Karma Yoga truly is.

So this verse concludes the threefold encouragement to Arjuna: to fight—or, he should fight, he should not grieve, and he should fight because:

- Nothing happens to Atma

- Sukshma Sharira, subtle body, travels on at the time of death

- It is Arjuna’s Dharma, his responsibility.

Now we begin the next topic—oops—yeah, the next topic: Karma Yoga.

Eṣā—this. This which has been abhihitā—this which has been literally “established,” but established in a sense of being taught to Arjuna.

This—eṣā, this—these teachings—abhihitā—which have been taught—te, unto you, Arjuna.

These teachings are sāṅkhye—with regard to sāṅkhya. Sāṅkhya has several meanings. It’s the title of our chapter 2, right? Sāṅkhya Yoga is the title of chapter 2. And here in this context, sāṅkhya means spiritual knowledge, wisdom. It has other meanings as well, but in this limited—in this case—it means spiritual wisdom, knowledge.

So he’s now making the transition. So up to this point, from verse 11 up to verse 38, he’s been teaching all of this with regard to sāṅkhya—spiritual wisdom.

Tu imam… tu imam—but you have to break those words apart—tu imam tu—“but now this.”

Imam śrṛṇu—listen, listen to this topic now, which is about buddhi-yoge—with regard to buddhi-yoge.

Now you’re thinking, “I thought we’re going to talk about Karma Yoga.” Well, Sri Krishna doesn’t call it Karma Yoga right here. He calls it buddhi-yoge. And buddhi-yoge means what you understand as Karma Yoga—for a very important reason.

Buddhi-yoge also has many meanings, one of which is “intellect,” but here it means “attitude.” Buddhi-yoge is the yoga of attitude—specifically, attitude towards your karma, attitude towards the deeds you do, the work you do.

We can say really, Karma Yoga is a yoga of attitude—attitude towards work. And let’s make that clear right off the bat. We’ll see a very common misunderstanding—a terrible misunderstanding of Karma Yoga is Karma Yoga is doing your duty. You’ve probably heard someone say that, “Oh, such-and-such is such a great Karma Yogi, they always do their duty.”

Well, doing your duty is absolutely not Karma Yoga. Doing your duty is the minimum to be a good person. Suppose someone does their duty, but they’re complaining about it all day long to every single person they meet—”Oh, I have to do this, oh, I have to do that”—they go on, complain. They do all their duties, but they do so with a terrible attitude, always complaining. That certainly is not Karma Yoga.

So Karma Yoga is not what you do. Doing your duty is not Karma Yoga. Karma Yoga is not what you do—Karma Yoga is the attitude with which you do something. It’s the attitude you have while you’re engaged in various actions. And we’re going to talk about that extensively, especially when we come to verse 47—the famous verse that’s so often quoted, karmaṇy-evādhikāras te—coming soon.

Here, Sri Krishna has just introduced the shift of topic:

Eṣā te’bhihitā sāṅkhye, Arjuna—this much that we’ve discussed is with regard to spiritual wisdom.

Buddhi-yoge tvimāṁ śṛṇu—but now, listen to these teachings about buddhi-yoga.

He makes it very clear: imam buddhi-yogam—imam this buddhi, this attitude. We have to translate it as “attitude” here. The word buddhi is not uncommonly used to mean buddhi—it can mean knowledge, it can mean wisdom, it can mean intellect, it can mean decisive thinking. Several meanings are there. But here, absolutely, it means attitude.

So śṛṇu—listen, imam—to this, to this teaching, this buddhi, this teaching, this attitude, yoga—which is a yoga, which is a spiritual practice. So he’s introducing here Karma Yoga in this way.

And how does he do—one more before he goes on:

Buddhyā yuktah yayā Pārtha—Pārtha, or Arjuna—yuktah—endowed with—yayā buddhyā— endowed with this attitude.

And this—my translation here, I think, could be improved. So I have “teachings” here, okay, but I think “attitude” would be a more precise translation in this context. So, endowed with this attitude, Arjuna—

Prahāsyasi—you will be freed—karma-bandham, from the bondage of karma.

Very important: prahāsyasi, you will be freed from the bondage of karma.

What is this bondage of karma, and what is the purpose of Karma Yoga? Let’s see that briefly here before we continue.

The bondage of karma is based on the fact that all conventional behavior, all conventional human behavior, is based on a twofold principle—rāga and dveṣa. You’ve heard these terms before, I think.

Rāga and dveṣa.

Rāga is attraction. Dveṣa is the opposite of attraction—revulsion.

Rāga means you chase after what you want. Dveṣa means you run away from what you don’t want.

So rāga—attraction to that which you think will make you happy.

Dveṣa is being repulsed by that which you think will make you suffer.

All conventional human behavior is driven by these two factors. Think about it.

This is the basic psychology of the Bhagavad Gita. Many teachers have commented on how there’s a lot of very important psychological teachings in the Bhagavad Gita. And this teaching about rāga and dveṣa is one of those important psychological teachings in the Bhagavad Gita—to recognize that all conventional human behavior is either rāga, a compulsion to get what you want, and dveṣa, a compulsion to avoid what you don’t want.

That shapes our lives. And you may think, “Well, that’s pretty normal.” And it is. It’s absolutely normal—but it’s problematic.

That which is normal, that which is natural, is not necessarily that which is desirable. Pardon me for pointing this out—I hear this argument, “But Swamiji, that’s normal. Everyone does it. It’s natural.”

That which is normal or natural is not desirable.

It’s natural for an infant not to know how to use the bathroom. That’s normal, that’s natural—but it’s not desirable. That infant has to grow up and learn to use the bathroom.

In a manner of speaking, we have to grow up so that we are not compelled by rāga and dveṣa.

Sri Krishna uses this term karma-bandham—bondage. And here’s the sense of the bondage:

Inside of you is this compulsion. A compulsion that makes you chase after whatever you consider to be a source of happiness. You’re compelled to do that—an inner compulsion is there. And similarly, an inner compulsion to avoid anything that you think will make you suffer.

That which compels you—it’s like having a demanding boss inside your mind. A boss that tells you: “Go there. Do that.” A boss that tells you: “Don’t go there. Don’t do that.”

You’re being bossed around. No one likes to be bossed around like that. We all like to be free to choose what we do in life.

Here’s a case where you’re being bossed around not by a superior supervisor in a workplace. You’re being bossed around by your own mind. You’re being bossed around by rāga and dveṣa—these inner compulsions, which, in a manner of speaking, deny you freedom.

And just to give a silly example:

You’re sitting comfortably in a chair—like I’m sitting comfortably in a chair. And you’re experiencing contentment. Then comes the thought, “Oh, I’d really like a cup of tea.”

Now that desire for tea is an example of rāga. “I want tea,” meaning you’ve made the judgment that a cup of tea is a source of happiness—or more, that gaining that cup of tea, getting that cup of tea, is essential for your contentment.

A moment before, you’re content in your chair. Now you’re no longer content. Why? You want a cup of tea. Rāga.

And that rāga is enough to drive you to get up from your comfortable chair, go to the kitchen, and make a cup of tea.

Now—you could have sat in the chair very comfortably. But that boss inside was telling you: “Get up! Go get a cup of tea.” That’s an example of rāga.

Dveṣa works exactly the same way. These are inner compulsions.

And it is the compulsivity of rāga and dveṣa that is the problem.

Let’s be very clear about it.

Oftentimes rāga and dveṣa are simply translated as “likes and dislikes.” That’s not a very helpful translation, because it’s natural to have likes and dislikes.

Many years ago, somebody asked my guru, Pujya Swami Dayananda: “Swamiji, do you want tea or coffee?” Swamiji was raised in South India—drinking coffee—so he says, “I’d like some coffee.” Perhaps he said, “I like some coffee.” I mean, he has a like. I thought he’s enlightened.

Enlightened people have likes and dislikes.

To like one thing, to like coffee more than tea, is an orientation that can certainly be present in an enlightened person.

What is not there is the compulsion—the compulsivity.

So if he likes coffee, if he’s sitting comfortably in a chair and the thought comes, “Oh, I’d like some coffee,” the question is—will he be compelled to get up from that comfortable chair, go into the kitchen, and make some coffee? No. That’s the difference.

Likes and dislikes are present for all, whether you’re enlightened or not.

Rāga and dveṣa, though, are not merely likes and dislikes. They’re a compulsion to get what you want and avoid what you don’t want.

The purpose of Karma Yoga, Sri Krishna says here, prahāsyasi karma-bandham—you will become free from the bondage of karma. The bondage to do karma. The bondage that comes due to that inner boss telling you: “Do this,” and “Don’t do that.” That inner boss, which is that compulsivity—the rāga and dveṣa, being compelled to chase after what you want and run away from what you don’t want. It’s as though you are being dragged about by rāga and dveṣa in our minds. That is certainly not freedom—that’s an absence of inner freedom. That’s a kind of bondage.

Sri Krishna calls it karma-bandham. Karma Yoga is a way to overcome being compelled to do certain karmas, being compelled to avoid other karmas. We’ll see how that works—we’ll see that as we continue. Let’s proceed. This is all introduction.

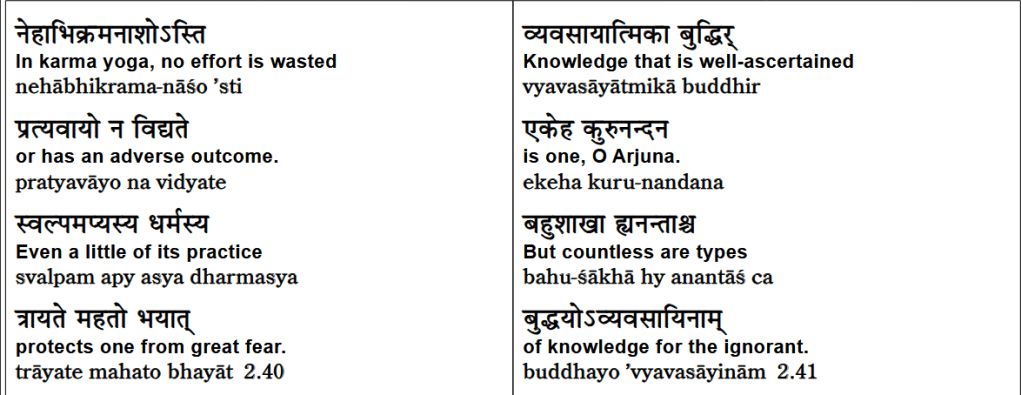

This verse needs some introduction. Apparently there was some confusion about what Karma Yoga means. So Karma Yoga is a spiritual practice—the spiritual practice of doing karma. And as we’ve just defined, we said that Karma Yoga is a spiritual practice in which you adopt a particular attitude in doing whatever karma it is you’re doing.

The confusion comes in ancient times: karma—the word karma frequently was used to refer to Vedic rituals. You may have heard the term Vaidika karma. Vaidika karma—a term meaning “the karma of the Vedas.” And there the word karma specifically means “rituals.” Vaidika karmas are Vedic rituals.

So it’s possible that in ancient times, because there was so much focus on Vedic rituals—much more so than there is today—because of that excessive focus on Vedic rituals, the term Karma Yoga could have been confused with “doing karmas,” meaning “doing Vedic karmas,” “doing Vedic rituals.” And what Sri Krishna wants to do here right off the bat is to make it extremely clear that Karma Yoga has nothing to do with doing Vedic rituals.

And what he does is he compares true Karma Yoga—which is a yoga of attitude towards actions—he compares it to doing Vedic rituals.

So with regard to Vedic rituals, he says:

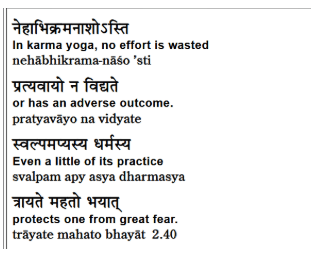

Na iha abhikrama-nāśo’sti—break the words apart: na iha abhikrama-nāśaḥ asti. Iha—here, means with regard to Karma Yoga properly understood. With regard to Karma Yoga, na asti—there is no abhikrama-nāśaḥ. There is no destruction of that which has begun.

This is a rather obscure reference to a problem in the performance of Vedic rituals. And that is—you begin a ritual. The rituals he is referring to are some rituals that were very long and complicated. So you have begun a ritual, but in the performance of the ritual, there are some errors made. Maybe some mantras are dropped, some offerings are missed, something goes wrong later in the ritual.

So even though you have begun the ritual correctly, if you have made errors later in the ritual, the benefits of the ritual are destroyed. That is called abhikrama-nāśaḥ—the destruction of that which has been started.

The rituals are meant to produce puṇya—karmic merit. Karmic merit that can bless you in this life and bless you in the next life. Karmic merit which can take you to heaven. But that karmic merit—puṇya—is only produced through the proper performance of a ritual. So if you begin a ritual properly and then make some mistakes, the ritual produces no puṇya. So there is abhikrama-nāśaḥ—there is a destruction of that which has begun, and therefore your effort is wasted.

But here, Sri Krishna says: na iha asti abhikrama-nāśaḥ—in Karma Yoga, there is no such thing. In doing Vedic rituals, if you begin properly and then make a mistake, all is lost. In Karma Yoga, if you begin properly and then go off base, you still are blessed to the extent that you started properly.

It’s not that—let me try to make this clear—if you have a complicated ritual with 100 steps and you make a mistake in the 99th step—the penultimate step—then theoretically the whole ritual could be wasted as a result of that one mistake.

Sri Krishna says that is not true in Karma Yoga. In Karma Yoga, you are blessed to the extent that you adopt the proper attitude toward what you do. And we’ll discuss all that much more.

Pratyavāyo na vidyate—also with regard to Vedic rituals, pratyavāya can mean “a mistake” in general, or it can mean—it’s often used in a technical sense—“a sin of omission.” You forget to do a particular ritual or you forget to do a particular step in a ritual. So there are all so many rules associated with these rituals, which makes it—frankly speaking—intimidating.

Sri Krishna says you don’t have to worry about that with Karma Yoga. You just do your best—with the right attitude.

Finally, he says one more factor. The rituals that are said—some of them are extremely elaborate. Some Vedic rituals go on for several days. You have to hire several priests. You have to have two or even three different ritual fires. There’s a lot—and so many mantras to be chanted. Very elaborate.

But here he says, with regard to contrast the Vedic rituals with Karma Yoga, he says:

Swalpam api asya dharmasya—asya dharmasya, of this dharma, of this practice of Karma Yoga—swalpam api, even a little bit of this practice of Karma Yoga—trāyate mahato bhayāt—trāyate—will help you cross over mahataḥ bhayāt—great fear.

Means that even a little bit of Karma Yoga can bless you tremendously.

A little bit of a ritual—what funny logic—a small ritual gives you a small result. If you want a bigger result, you need a bigger ritual. Like, if you’re pouring ghee into a ritual fire—if you want a small result, you pour a little bit of ghee into the ritual fire. If you want a bigger result, you pour more ghee into the ritual fire. If you want something really big (I’m being facetious), you better be ready to pour gallons and gallons and gallons of ghee into that ritual fire.

Sri Krishna says Karma Yoga isn’t like that at all. He says even a little bit of the performance of Karma Yoga will bless you a lot.

Here’s a better way of understanding: even a small shift of attitude can create a huge change in your attitude towards what you do. That’s what—in your attitude towards your actions—this is the key.

Karma Yoga is a small adjustment to your attitude towards what you do in life—towards your karmas. And we’re going to see that attitude in some detail after we finish this introduction.

He continues:

Without some introduction, this verse is almost—it’s hard to get any meaning at all. “Teachings that are well ascertained are one in this matter, O Arjuna. But countless are the many branches of teachings for those who have not ascertained properly.” What does that mean?

It’s a literal translation, but we need the context. And the context is really the goals of life and how we pursue those goals of life. This is a very fundamental topic.

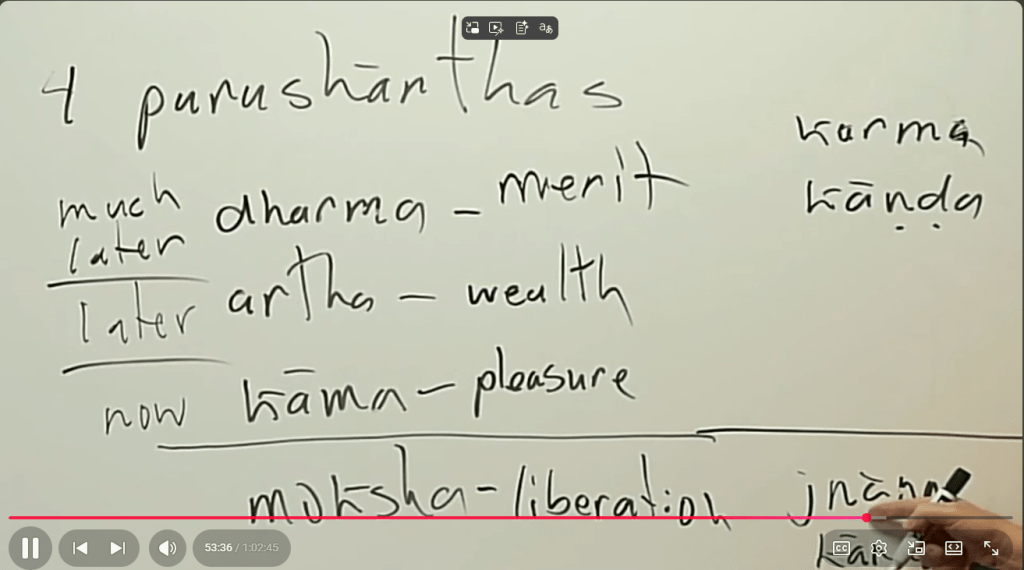

And let me show you on the board. When we speak of goals of life in the Hindu tradition—you may have seen this teaching before—it’s common to refer to—when we talk about goals of life—it’s common to refer to four…

(Sorry, let me try to write clearly.) Four puruṣārthas.

That’s not… Sorry, I’m writing too high—I can see—I want you to see this clearly.

Four..

.

There we go—four puruṣārthas. Puruṣa-artha. Here, artha has many meanings—here it means “goal.” Puruṣa—person. Puruṣārthas are the four goals pursued by people. This is fundamental, and we need to understand this to understand this next verse.

Those four puruṣārthas—you may have seen this topic before—very important.

The four puruṣārthas are:

Dharma, Artha, Kāma, and Mokṣa—are the four puruṣārthas, the four goals of life.

Just a brief definition of them, starting with Kāma—pleasure. Fundamental to life—we all want pleasure, we all want to avoid pain. Kāma is a goal of life, but we also want Kāma. We want pleasure—not just today, but we want Kāma tomorrow, and for the rest of our lives. For the reason of maintaining Kāma in our day-to-day lives, we’re going to need Arta. And here we’re going to translate it simply as wealth.

Notice the purpose of Arta. The purpose of wealth is not for its own sake. Having a lot of money in a bank account doesn’t help you unless you spend it to produce Kāma, pleasure.

And finally, Dharma. Dharma here is the accumulation of religious merit—puṇya—and avoiding religious demerit—pāpa—so that whatever happens in your next life will have more Kāma. The principle is: if you have bad karma, bad karma will prevent you from enjoying pleasure. Good karma can help you enjoy pleasure. So therefore, Dharma is, and we can say, Dharma is the accumulation of merit.

And I want you to see a progression of these three. The order is always Dharma, Arta, Kāma, Mokṣa. But logically, there is an order that begins with Kāma.

Kāma means pleasure now, in a present moment. Arta means pleasure—pleasure is maybe too weak a word—contentment, happiness, peace, joy, love, whatever it is that makes you feel happy, content, and peaceful. That’s what we mean here by Kāma—not mere sensual pleasure. It’s not like—it includes sensual pleasures but not limited to that. So, true pleasure, happiness, contentment—we want it now. That’s expressed with the word Kāma.

We want it tomorrow and for the rest of our life, and for that reason Arta is also a goal of life. And we want it not only in the rest of this life, but we want it in the next life—whatever follows this life—and that’s a way of understanding Dharma, accumulation of religious merit.

So notice here—you want, let me use the word “contentment and peace.” You want contentment and peace now. That’s a pursuit of Kāma. You want contentment and peace for the rest of your life—therefore, you pursue Arta, wealth. You want contentment and peace in whatever follows this life—that’s called Dharma, the accumulation of merit.

And this pretty much summarizes conventional life—conventional life is a pursuit of pleasure. I’ve been saying contentment and peace—the pursuit of contentment and peace now, later, and Dharma we’ll say “much later,” which means after this life. This is conventional living. Conventional life. Conventional thought.

Of course, Vedānta and the teachings of the ancient ṛṣis go far beyond conventional thinking. The ṛṣis understood very clearly that the true source of the conventional life—of the contentment and peace that you seek now, the contentment and peace that you seek for the rest of your life, the contentment and peace that you seek in later lives—the true source of that contentment and peace is already within you. It’s already your true nature.

Therefore, the one more puruṣārtha, one more goal of life is Mokṣa—literally “liberation” or “freedom.” Liberation or freedom—freedom from suffering. Don’t narrowly define it as “freedom from rebirth.” It does mean freedom from rebirth, but it has more meaning than that.

Right now—freedom from the struggle to gain contentment and peace. Notice: if you’re pursuing Kāma, Arta, and Dharma, it takes a lot of effort. This is conventional life—a lot of effort to gain pleasure now, contentment and peace, let me say. A lot of effort to gain contentment and peace for the rest of your life. A lot of effort to gain contentment and peace in your later lives—you have to accumulate a lot of religious merit in order to enjoy contentment and peace in later lives. And in ancient times, doing a lot of rituals was involved—a lot of work. A lot of effort. A lot of effort.

Here’s the irony of Vedānta: a lot of effort chasing after what you already possess. You’ve heard it said so many times that your true nature is divine. You’ve heard it said so many times that the true source of happiness and peace is within you. These are not just mere sayings—this is a reality to be discovered.

And the irony of Vedānta—and the irony of life—is that we spend so much time and effort and struggle trying to gain the happiness and contentment that’s already your true nature.

Mokṣa—liberation—is the—you’ll hear me most often use the term enlightenment. Enlightenment in a sense of gaining that discovery—discovering that true source of happiness and contentment within you. Mokṣa—literally liberation or freedom—but the sense of Mokṣa is the discovery that the true source of happiness and contentment, peace, love, and joy is within you.

With that discovery, you are liberated or freed from the struggle—the struggle of daily life, the struggle of chasing after pleasure now, chasing after pleasure for the rest of your life, chasing after anything for your next life. All of that effort and struggle goes away. There is liberation or freedom from that struggle and difficulty.

So we need to understand these four puruṣārthas to understand this verse and the verses that follow. And here’s how it works:

The Vedas—the source scriptures on which the entire Hindu tradition is based, including the teachings of Vedānta—those Vedas are specifically meant to help us gain these four puruṣārthas. Specifically, the four goals of life are meant to be pursued with the help of the Vedas.

The Vedas have two parts. One part of the Vedas—this terminology is important—one part of the Vedas is that on the—yeah, that’s visible—one part of the Vedas is called karma-kāṇḍa. The karma-kāṇḍa is the—kāṇḍa means part or section—karma (remember, I said karma in this context means rituals). Karma-kāṇḍa is the portion of the Vedas concerned with rituals.

And the karma-kāṇḍa is actually the largest part of the Vedas. The Vedas have several parts, and most of those parts are included in this karma-kāṇḍa.

There is a smaller portion of the Veda called—that’s showing up, yeah—called jñāna-kāṇḍa—the portion of the Veda concerned with jñāna-kāṇḍa, with spiritual wisdom.

Turns—you know this already, but just to make sure that we understand as jñāna-kāṇḍa, the portion of the Vedas that is concerned with spiritual wisdom—that portion is found at the end of each of the four Vedas. That’s why we have the term Vedānta—Veda–anta. The anta—the last portion of the Vedas—is Vedānta. It is the jñāna-kāṇḍa, and it’s the portion of the Vedas that’s concerned with gaining mokṣa.

So the Vedas are huge. And in that huge collection of Vedic teachings, most of those teachings are involved with various rituals and prayers and meditations meant to help you gain Dharma, Arta, and Kāma—even Kāma.

The idea being that by doing rituals, those rituals will yield their religious merit, yield their results, and they can yield the results very quickly.

The blessings you get from a ritual—some of those blessings come immediately. In fact, you know that already. You do some rituals, you feel a sense of contentment and peace. So when you do rituals, some of the benefit blessings come now. Some of the benefit and blessings from those rituals will come later in this life. Some of the blessings and benefits of those rituals will come much later—means in later lives.

That’s what the karma-kāṇḍa is involved with: the performance of rituals to help you gain kāma, artha, and dharma. As distinguished from the jñāna-kāṇḍa, whose purpose is to help you look within yourself to find that what you seek through kāma, artha, and dharma—that what you seek is already within you.

And the jñāna-kāṇḍa, excuse me, is that which helps you discover that inner divinity. And having discovered that inner divinity, you’re then freed from the struggle of pursuing dharma, artha, and kāma.

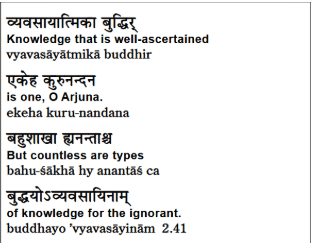

We need to understand this to understand this verse. Now the verse will make sense—otherwise, I’m afraid it won’t make any sense at all. Okay, so returning now to our verse—and here, buddhi we’ll take in a sense of knowledge, wisdom, spiritual wisdom.

So this buddhi, the spiritual wisdom, which is vyavasāyātmikā, whose nature is vyavasāya. Vyavasāya is discernment, ascertainment. So this wisdom, this understanding, which is vyavasāyātmikā, which is well ascertained—eka iha, kurunandana.

Iha here, in this matter, in this teaching of karma yoga, it is eka, it is one. Kurunandana, O beloved one of the Kuru lineage, Arjuna—it is one. Now what do we mean by one? This karma yoga is with regard to a single direction in life, and that single direction in life is the pursuit of mokṣa, as opposed to the multiplicity of seeking kāma, artha, and dharma.

There’s multiplicity—and multiplicity also of all the rituals, or various rituals in pursuing dharma, artha, and kāma. This is in ancient times—you’ll perform many different rituals for the sake of dharma, artha, and kāma.

But the pursuit of mokṣa is eka—eka iha buddhi—there is one understanding, one truth, we can say: the truth of your own inner divinity.

On the other hand, bahu-śākhāḥ hi anantāḥ ca—hi, indeed anantāḥ, limitless, and bahu-śākhāḥ, countless is a better translation. Anantāḥ, countless, and bahu-śākhāḥ, having many branches—having many branches are the buddhayaḥ, the teachings.

The teachings avyavasāyinām, for those who do not have the one direction. Vyavasāya is this clear ascertainment of the ultimate goal of life. Vyavasāya, the clear understanding that mokṣa is the ultimate goal of life.

But for those who are avyavasāyinām—for those who lack that discernment, for those who lack that discernment that mokṣa is the ultimate goal of life—for them, buddhayaḥ, teachings, are bahu-śākhāḥ, manifold, anantāḥ, countless.

Those manifold, countless teachings are all the rituals that are expressed in the karma-kāṇḍa. The karma-kāṇḍa contains numerous rituals, which are meant to help you gain dharma, artha, kāma—as opposed to the jñāna-kāṇḍa, which has one central teaching.

The one central teaching of the jñāna-kāṇḍa is Tat Tvam Asi. The one central teaching of the jñāna-kāṇḍa is Tat Tvam Asi—”you are that.”

And here in this rather obscure verse, Śrī Kṛṣṇa is contrasting that. The one clear teaching, Tat Tvam Asi, found in the jñāna-kāṇḍa of the Vedas, is contrasted here with the multiplicity of rituals meant to help you gain dharma, artha, kāma—the multiplicity of teachings that are found in the karma-kāṇḍa.

When we continue, we’ll see how Śrī Kṛṣṇa is actually highly—you’ll be surprised—Śrī Kṛṣṇa is highly critical of the excess of ritualism involved with that karma-kāṇḍa. He is quite clear in his criticism of that, and we’ll see that in our next class.

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||