Gita Class 013, Ch. 2 Verses 29-36

Apr 3, 2021

YouTube Link: Bhagavad Gita Class by Swami Tadatmananda – Ch.2 Verses 29-36

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

Good.

Welcome to our weekly Bhagavad Gita class. We’ll continue today in chapter 2. We’ll begin, as always, with some recitation. As I’m reciting, please glance at the meaning, so the meaning is in your mind when you repeat after me.

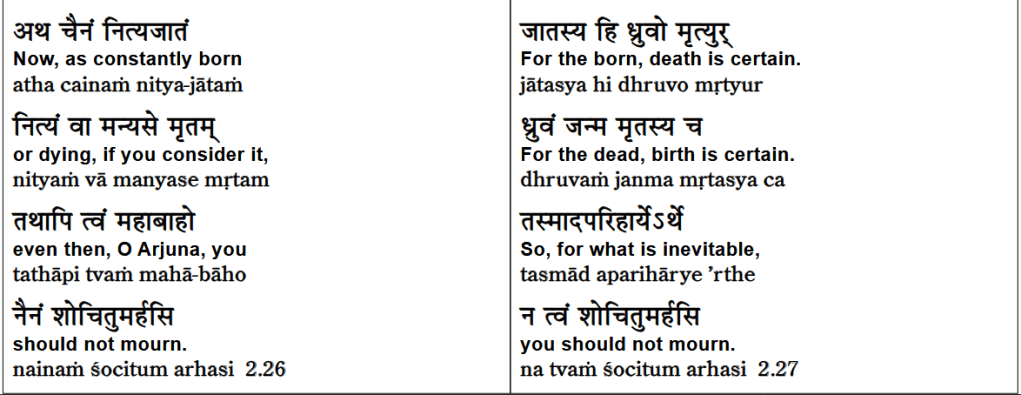

Verse 26.

Let’s return to where we left off. We’ve concluded our prior verse with our prior class with verse 28. Just to set the context: from verse 11 onwards in chapter 2, Shukrishna begins his Upadehsha, his spiritual teaching to Arjuna. And he begins by saying, Arjuna, there is no reason for you to grieve. And then he goes on to give a number of reasons for that—Arjuna has no need to grieve.

The first reason, of course, is that while many bodies will fall dead on the battlefield, nothing will happen to Atma. The true self of each person will be utterly unaffected by the bloodshed on the battlefield.

Then we saw in the last class, Shi Krishna shifted to a second reason for Arjuna not to grieve. And that first reason was with regard to Atma, satchidananda, your true self. Second reason was from the standpoint of the Sukshma Sharera, the subtle body, that which enlivens the physical body. And as we discussed in some detail, should not be confused in any way at all with Atma. Atma and Sukshma Sharera are two entirely different realities.

So that Sukshma Sharera, at the time of death, detaches itself from the physical body, travels on driven by the forces of karma, and takes on new body. That’s what this last verse said, verse 28. All those Sukshma Shareras are at first unmanifest, vyaktamadhyani, and then they acquire physical bodies and become vyaktam—manifest—and vyaktam nidhanani. Finally, in the end, all of those Sukshma Shareras again become avyaktam, unmanifest, when the bodies die and the Sukshma Shareras travel on.

So this is the second of actually three reasons that Sri Krishna gives Arjuna that he shouldn’t grieve. We have a little bit more on the Sukshma Sharera, and then we’ll see the third reason in just a couple more verses.

Okay, with that introduction, we pick up the thread with his verse with the longer meter.

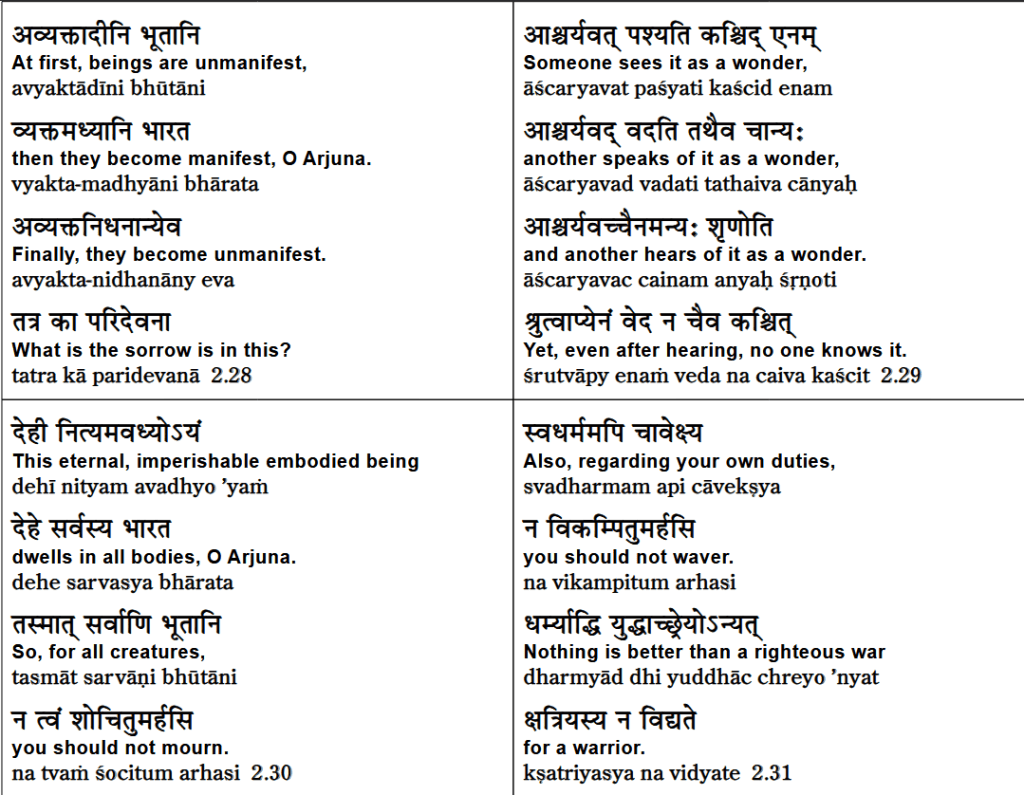

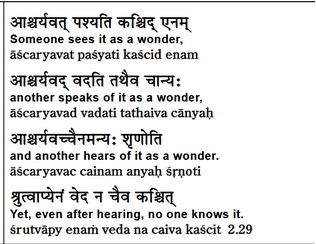

Aashchāryavat is something really amazing—amazing because of its rarity—and that’s the context here. The rarity of this wisdom being imparted by Sri Krishna to Arjuna. Arjuna didn’t understand properly that nothing would happen to Atma when the bodies fall in the battlefield. Arjuna did not understand that the Sukshma Sharera of each person would travel on at the time of death.

This is not always well understood. You may understand very well, but the majority of people have not had the opportunity that you and I have had to explore these teachings very thoroughly. So for that reason, these teachings and this wisdom is considered rare. Here the word Aashchāryavat, which means—better translation is amazing—but amazing in the context of it being exceedingly rare.

And that’s what Sri Krishna comments on. He says Aashchāryavat—it is amazing, it is exceedingly rare. What is it? What is exceedingly rare? That kaschid, that someone, Pashati, should see, enam, this one. This one could refer to Atma, could also refer to Sukshma Sharera, and here there is no reason, no need to differentiate. The enam, this Atma, or this Sukshma Sharera, recognizing which there is no reason to grieve at the time of death.

And Pashati, kaschid Pashati, someone sees—but see is not in a physical sense, but in a more metaphorical sense. See in a sense of to know, like when we say in English, “Do you see what I mean?” You can’t see a meaning; it’s a very common metaphorical usage. I think in all languages, including Sanskrit here.

So, kashchatt Pashati—it’s amazing that someone should see this truth, that someone should recognize this fact. And who were those that discovered this truth in the first place? The ancient rishis. In fact, very appropriately, those ancient rishis are called mantra dhrashtara—literally the seers of the mantras. We’ve probably read some place—the ancient seers. Seers, in the sense that they could see what others could not see—they could discover what others could not discover.

So, this first line refers to the ancient rishis—how amazing it is, and how rare it is, that those rishis that made this discovery—those rishis themselves were exceedingly rare.

Not only were the rishis rare, but in the second line, aschādiyavat—it is amazing, it is exceedingly rare. So, rare—what is exceedingly rare? At the end of the second line, chā, and anyaha It’s exceedingly rare that others, tatā eva, in the same manner, vādhati, should speak. First line, pāśyati—should see, should discover. Second line, vādhati—speak. So, it’s exceedingly rare that others should speak, in the sense of should teach what the ancient rishis discovered.

First line refers to the ancient rishis. Second line refers to all of our gurus, all of our teachers, the lineage of teachers. So, first line—how amazing it is that these ancient rishis discovered this truth. Second line—how amazing it is that our generation after generation of gurus, teachers, continue to vādhati, continue to teach the same wisdom.

Third line, aschādiyavat, third time—amazing it is, how rare it is that in the middle of the line, anyaha—others, shrenoti—should hear. Backing up—enām. You see, breaking up the words, aschādiyavat cha enām. enām, like in the first line—this one, this atma, or this sukṣma-sharīra, this truth. So, the third line says how amazing it is, how rare it is that others, anyaha, shrenoti—should hear this teaching and should understand this teaching.

The third line, of course, is referring to students. First line—rishis, second line—gurus, third line—students, who shrenoti, who hear.

Then the fourth line is the—they call it the kicker. What is the kicker? The kicker means something surprising.

Fourth line—shrutua, breaking the words apart: shrutua api enām. And shrutua—we have to get the last line. Well, shrutua api enām. And having, api—even shrutua, having heard enām, having heard this, so there are others—others who, last word, cāścād, and there is still someone, some others, some students will say. Skaścād, some student, shrutua api enām, having heard this teaching taught from by a guru, na veda—but doesn’t understand.

Look—very nice, the succession: amazing that the rishis discovered it. Second line—amazing, rare it is that the gurus teach this. Third line—rare it is that a student has an opportunity to hear it. Fourth line, which is the little joke—it’s not amazing. It’s not a—notice the word aścād, but it’s not present in the fourth line, because it’s not amazing at all that some students hear this teaching and na veda—they don’t understand, they don’t get it.

And so, not really a joke, but it’s amazing that the rishis taught it, that the rishis discovered it. Amazing that the gurus teach it. Amazing that we can learn these teachings. But it’s not amazing. It’s not surprising at all that so many people hear this teaching and they don’t get it.

Why is it not amazing? This is a big and important topic. We’ll just touch upon a very briefly here. These teachings are able to impart knowledge to you—only if you are ready to receive this knowledge. Only if you are a prepared student. This prepared student has an important term.

The Sanskrit term, you should know, is adhikādi. Adhikādi in this context means a prepared student. We’re not speaking Hindi now, so we’re not talking about somebody who’s in charge, as it would mean in Hindi. In this context, as a Sanskrit word here, adhikādi means qualified student or prepared student.

And if you are not an adhikādi, if you’re not a prepared student, you could hear this taught by the best teacher available—you won’t get it if you are not adequately prepared.

An example I’ve given in many classes, I’ll give it one more time. When I was in college, I had to study calculus. In fact, a lot of—I think—four semesters of calculus. So based on that, I made up a story about a student in the calculus class.

The student attends every class, takes copious notes, does all of this, comes to the end of the semester, the student writes the exam and gets zero points on the exam. How is that possible? Well, it’s certainly possible because this student never studied algebra, which is a prerequisite—never studied geometry and trigonometry, which are prerequisites. This student was still struggling with long division—not a prepared student. Therefore, even though he attended the classes, nothing went in.

So for that reason, the last line refers to the one who lacks the state of being an adhikādi, a qualified student, and it’s not surprising at all. There are so many, and they don’t get it.

Okay, continuing.

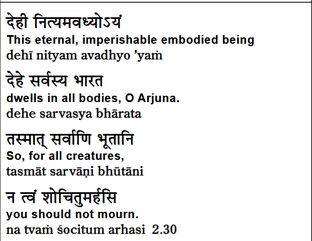

This verse really concludes a discussion that began with verse 11. Beginning with verse 11, Shri Krishna began teaching Arjuna that he didn’t need to grieve because nothing happens to Atma at the time of death and a Sukshma Sharira travels on at the time of death.

Therefore, with regard to the Dehi—remember I gave that expression? Deha is body. Dehi is one who possesses a body or one who is dwelling within the body. As the in-dweller of the body, Dehi can refer to Atma, Dehi can also refer to Sukshma Sharira. In this context, it doesn’t make any difference because from both standpoints, Arjuna is told there’s no reason to grieve.

So actually the better interpretation here is Dehi referring to Atma. Perhaps it could mean either Atma or Sukshma Sharira, but I think Atma is a better meaning here because of the adjectives that follow.

So that Dehi, that in-dwelling true Self, Satchidananda Atma—that indwelling Self is Nityam, eternal, unborn, uncreated, and unchanging. Sukshma Sharira changes. Dehi, the Nityam—eternal in the sense of unchanging—definitely refers to Atma, not Sukshma Sharira. So that indwelling Self is Nityam—eternal. Avadyaha—indestructible, can’t be killed. Iyam—this one. This one—that Dehi in the body—Sarvasya, of all people, of all beings. The Iyam Dehi, this indwelling Self, who dwells—Dehi—in the bodies—Sarvasya—of all people, is Nityam—eternal and avadyaha—indestructible.

Bharata, Arjuna, O descendant of King Bharata. Tasmat—therefore—and here’s the conclusion. Winding things up at the discussion that began with verse 11: Tasmat—therefore Arjuna, in the second and the final line, Twam—you, Na Arhasi—you have no reason Shodh Chitum—to grieve. There is no reason for you to grieve. You should not grieve Sarvani Bhutan—in the third line—for all beings, for all these warriors who are about to fall on a battlefield.

Remember the context. This is the morning of the first of the 18 days of battle. No one has died yet, but shortly after this dialogue is over, thousands and tens of thousands or more will die in that battlefield.

So Sri Krishna concludes this subject matter. Therefore, Arjuna, there is no reason for you to mourn.

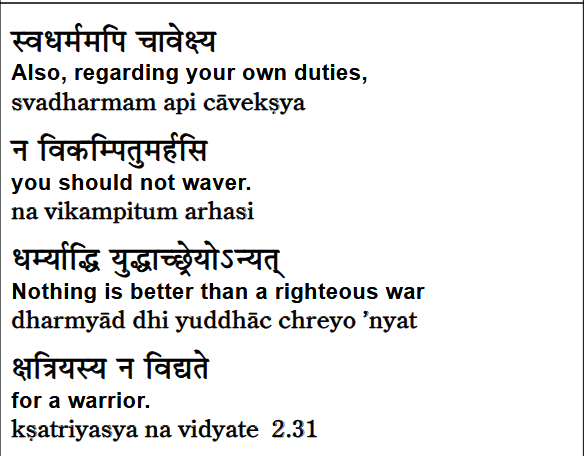

Now, we’re going to see another shift of context. We said that Sri Krishna said, back in verse 11, there is no reason for you to mourn. Then he gave the first reason—because Atma, nothing happens to Atma at the time of death. And with the second reason—for the Sukshma Sharira, Sukshma Sharira travels at the time of death. So for those two reasons, there is no reason to mourn, and now comes a third reason. And therein lies the last of the reasons given in this second chapter.

Svadharmaam api ca api cha—and also aveksya—having in view, aveksya—keeping in view with respect to svadharmaam—your svadharma, your duties, your own duties. Aveksya—with regard to your own duties, api cha—also with regard to your own duties, Arjuna. Na Vikaampitum Arhasi—Na Arhasi—you should not Vikaampitum Arhasi. You shouldn’t waver. You shouldn’t vacillate. You shouldn’t be indecisive about fighting this war.

In fact, Arjuna has to fight this war. So, the first reason that Arjuna shouldn’t grieve was with regard to Atma. Second reason was with regard to Sukshma Sharera. Third reason now is with regard to Suadharma—Arjuna’s duties.

Why? Dharmat. He. You have to break the words apart. Oh, what a mess. Dharmat. He. Yudhat. Shreyas. Anyata. Breaking the words apart: Dharmat. He. Yudhat. Shreyas. Anyata.

So the He means because. So first half, Shri Krishna says you shouldn’t have any doubts with regard to your Suadharma. He—in the third line—because Anyata Shreyas—anything better Yudhat—than a war—but not any war. Dharmat. Dharmiyat Yudhat. Dharmiyat means a dharmic war. Dharmiyat Yudhat—anything better than a righteous war.

Remember, at the very beginning of our study, we were careful to define a righteous war—a dharma yudha. And we gave a very specific reason, a very specific definition. The definition was: a dharma yudha is a war in which not fighting the war has worse consequences than fighting the war. This Mahabharata war was a dharma yudha. For Arjuna not to fight the war—which would have led to the loss of the Pandavas, who would definitely have lost that war if Arjuna did not fight—so if Arjuna failed to fight, the consequences would have been worse.

So, Shri Krishna now says that with regard to your own duties, you should also fight the war. That’s a third reason for not vacillating about fighting the war. Why? Because Anya Shreya ha—anything better than Dharmiyat Yudhat, anything better than a righteous war, na vidyate—doesn’t exist. There is nothing better than a righteous war.

kshatriyasya—this is the important word. For a kshatriya. Please don’t leave that word out, because if you do, then you say there’s nothing better than a righteous war. War is still war.

Righteous or unrighteous, war is horrible. So here the key word is Kshatriyasya—for a kshatriya. From Arjuna’s personal standpoint, as a kshatriya, as a member of the warrior caste, from that very specific perspective, Shri Krishna says there’s nothing better than a righteous war.

Why? And he’s going to explain why in the coming—one in the coming verses. Look in the next verse. Yeah, next verse right away will give. So why is it that Shri Krishna can say to Arjuna, there’s nothing better for you as a kshatriya? There’s nothing better than a righteous war?

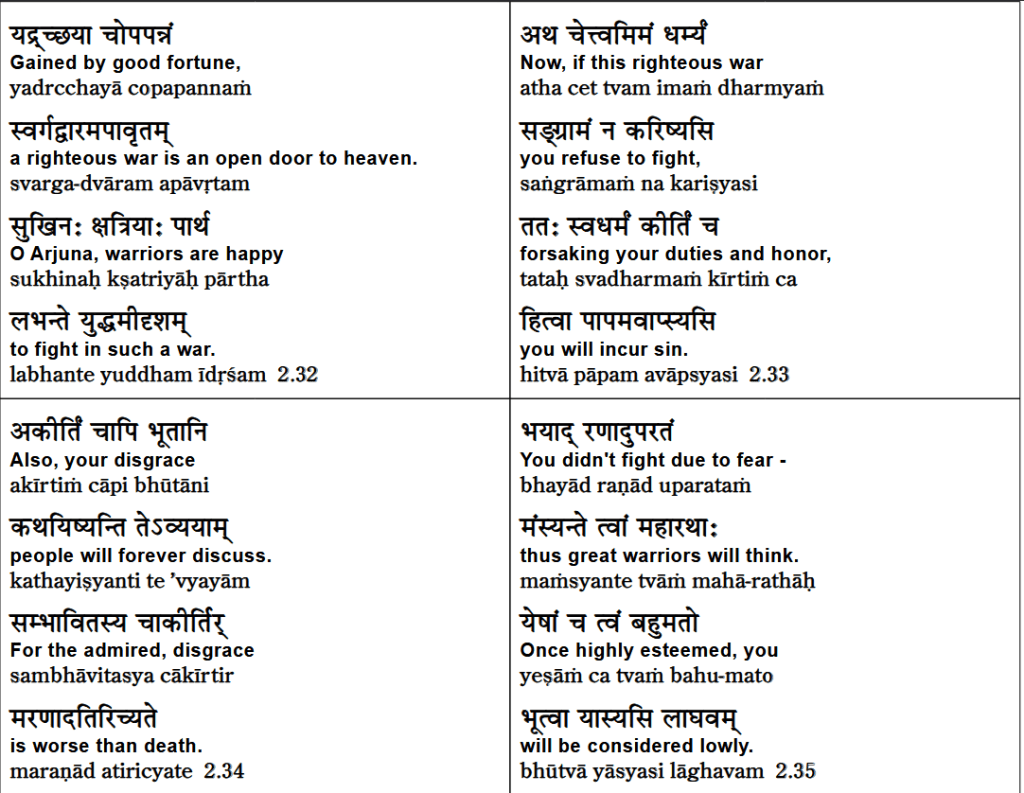

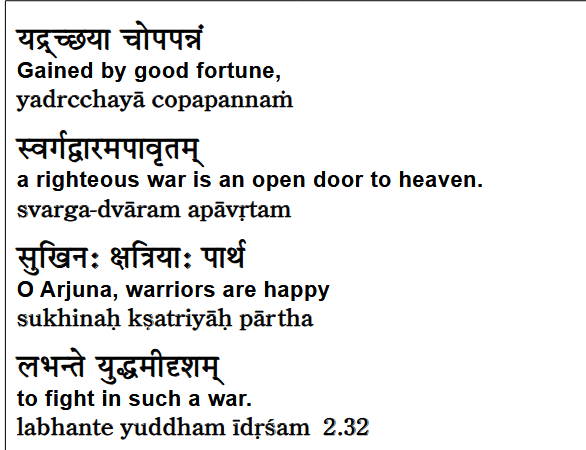

Yadṛcchayā chopapannaṁ—separate those words: cha and upapannaṁ. This is referring to the war, the battle. This war, which is upapannaṁ, which is gained, which is—that what you possess is upapannaṁ. And Arjuna possesses this war yadṛcchayā—by chance. That which is upapannaṁ—acquired yadṛcchayā, due to good fortune—would be a good translation here.

Yeah, a battle gained by good fortune—that’s a nice translation. This battle, which is gained by your good fortune, is svarga-dvāraṁ apāvṛtam—it is a dvāraṁ, a doorway to svarga, to heaven, which is apāvṛtam, which is wide open. It is a wide open gate or doorway to heaven.

Now, how can a battle, a war, be a gateway to heaven? Well, first of all, it’s not a gateway to heaven for everyone—but it is for a kshatriya who is fulfilling his dharma. And here’s—actually—the commentator makes a very interesting observation here.

He says, if you do a lot of rituals in your lifetime, you will accumulate a huge amount of puṇya, good karmas, which will determine that you will definitely go to heaven. If you do so many rituals, you can accumulate enough good karma that it is virtually guaranteed that you go to heaven. But you have to wait until you die to go to heaven.

This is a commentator’s observation. And he says, for a kshatriya, dying in a battle is better than doing all these rituals.

Why? By fighting the war, you’re accumulating good karma—just like by doing the rituals, this other fellow was accumulating good karmas. For the kshatriya, by fighting the war, by doing svadharma, by fulfilling your duties, you are accumulating good karmas. And then you don’t have to wait, because you’re probably going to die right there and then on the battlefield. This is a commentator’s perspective.

So in that sense, this battle gained by your good fortune is an open gate to heaven. It’s better than a lifetime of rituals.

And he continues—Shri krishna continues: Pārtha, O son of Kunti—Pṛthā is one of the names for Kunti—son of Kunti, Arjuna.

Kṣatriyāḥ—warriors, members of the kṣatriya caste—are sukhinaḥ, are happy. They are happy.

Why? Labhante—because having gained. Those kṣatriyas are happy because labhante—they gain yuddham, a battle, īdṛśam, of this kind. Of this kind means a dharma yuddha—a righteous war. A war in which, by fighting, those kṣatriyas can fulfill their duties. And by fulfilling their duties, they accumulate good karma. And if they should happen to die on a battlefield, their good karmas will take them to heaven.

Now, with some interesting verses:

The next several verses—Shri Krishna uses an interesting tactic to convince Arjuna to fight. The tactic is to consider the consequences if he doesn’t fight—the consequences of failing to fulfill his svadharma, his duties as a warrior. And that’s what he says.

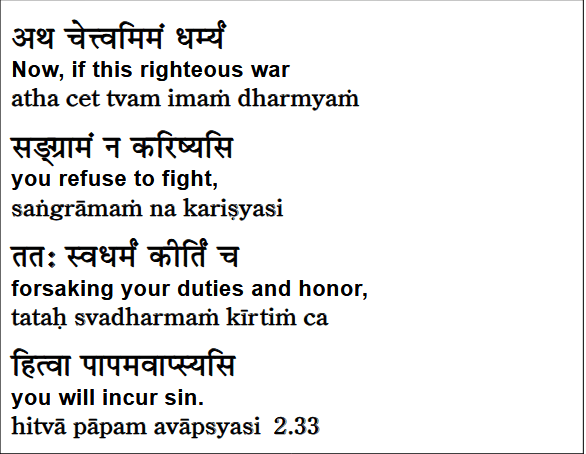

Atha cet—cet if, atha now. So this now is setting up this—I think—three, four verses about if you don’t fight.

Cet—if, tvam—you. Tvam, you in the middle of the first line, you, Arjuna. Second line—na kariṣyasi—if you do not do, if you do not engage yourself. Engage yourself in what? Imaṁ—this dharmyaṁ, righteous saṅgrāmam, battle.

In this righteous battle—na kariṣyasi—if you do not engage yourself in this battle, Arjuna, tataḥ, in the third line, then what will be the consequences?

Svadharmaṁ kīrtiṁ ca hitvā—hitvā, giving up, forfeiting. Forfeiting what? Svadharmaṁ—the fulfillment of your own duties. Kīrtiṁ ca—and fame. The fame of being a glorious warrior on a battlefield. Both of these—hitvā—abandoning them both, pāpam avāpsyasi—you will gain sin.

Pāpam avāpsyasi, Arjuna—you will gain sin, hitvā—having abandoned svadharmaṁ, your own duties.

And kīrtiṁ ca hitvā is making a reference to the fact that if Arjuna fails to fight, the consequences are two fold. There is an immediate consequence and a later consequence.

The immediate consequence is the word kīrtiṁ hitvā—abandoning fame, giving up fame, which means if Arjuna fails to fight, he’ll become the opposite of fame, as in infamous. And Shri Krishna is going to talk about that in the next verse.

So Arjuna is going to be despised by all these mighty warriors if he abandons the battlefield. And that is the first of two consequences—a consequence that happens immediately, right there and then on the battlefield.

Then there’s a second consequence—a delayed consequence. And that is hitvā svadharmaṁ—having given up his own dharma, having failed to carry out his own duties—pāpam avāpsyasi, Arjuna, you will incur sin. And having incurred that sin, you will suffer consequences later—karmic consequences later—either later in this life or in the next life.

So here, Shri Krishna is pointing out two consequences: an immediate consequence of losing fame, glory, and a later consequence of acquiring sin, which will, according to the laws of karma, cause Arjuna to suffer—later in this life or in the next.

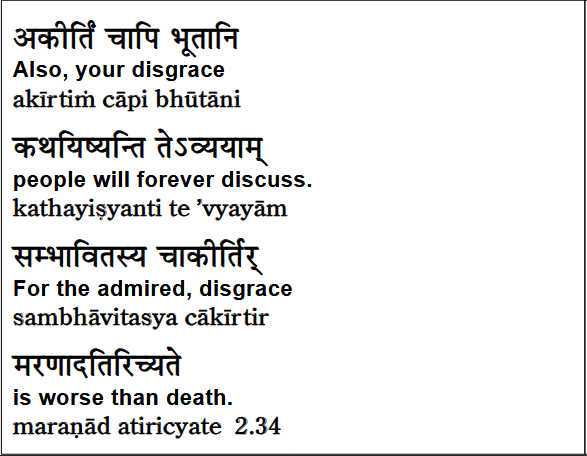

Now Shri Krishna is going to elaborate on his loss of fame—the immediate consequence:

Bhūtāni in the first line—and ca api, and also. Bhūtāni—literally “creatures,” but in this context, “people.”

Bhūtāni—people. Second line—kathayiṣyanti—good for a Sanskrit students. Future tense: “will say.” Bhūtāni—people, kathayiṣyanti—will say, will talk about te—your, go back to the top—akīrtiṁ. Kīrti is fame, akīrti—infamy. When a great warrior walks away from a battlefield—remember Arjuna was, back in chapter one, Arjuna was ready to walk away from the battlefield and go live in a cave up in the Himalayas. So Arjuna is considering abandoning the battlefield.

So therefore, and if he leaves the battlefield with all the warriors watching him—what will they think? What will they say?

So bhūtāni—all people—kathayiṣyanti—will talk about te akīrtiṁ—they’ll talk about your infamy. Te avyayaṁ akīrtiṁ—your unceasing infamy, your terrible infamy.

Or—they’ll talk about avyayaṁ—I can’t really take it as a participle. My translation here is “forever.” “Forever” is an adverb. Technically, that can’t be an adverb. So the translation here is not correct. “Unceasing infamy” would be a better translation here.

And Sri Krishna continues:

Sambhāvitasya ca akīrtiṁ ca. And sambhāvitasya—for someone who is famous, like you, Arjuna—and Arjuna is famous amongst all the warriors on the battlefield. There are maybe several dozen who are really, really famous, well known, and Arjuna is certainly one of the most well-known amongst all the warriors.

So sambhāvitasya—for someone who is famous, for someone who is highly regarded—honorable, that’s a good translation. For someone who is highly regarded, akīrtiḥ, the opposite of fame, is infamy—or here, “disgrace” is a nice translation. Disgrace maranād atiricyate—disgrace is atiricyate, is worse than maraṇād, than death. For someone who is highly regarded, infamy is worse than death.

Now we have to understand the context. Arjuna is not an ordinary person like you and me. Arjuna is this famous warrior, and famous people are held to a different standard. If there’s a big politician, a big politician is expected to act in politically wise ways. Or if there’s a famous—I don’t know if this is a good metaphor—but actors in Bollywood and Hollywood are famous too. Maybe the point is, being famous, they’re always under public scrutiny. What a politician does is subject to public scrutiny. What actors and actresses do is subject to public scrutiny.

And when these famous people rise very high, there’s a saying: the higher you rise, the further you can fall. So someone who’s come up very high in life stands to lose a lot through this public shaming—we’ll call it—public shaming. So if they do something wrong, if a very important person makes a mistake—if an insignificant person makes a mistake, who cares? If a beggar on the street makes a mistake, no one really cares. No one notices. But when a very famous person, a highly regarded person makes a mistake, everyone notices. And there is what’s called public shaming of that person. The higher you go, the further you have to fall.

Interesting argument—for not rising so high in life. All right.

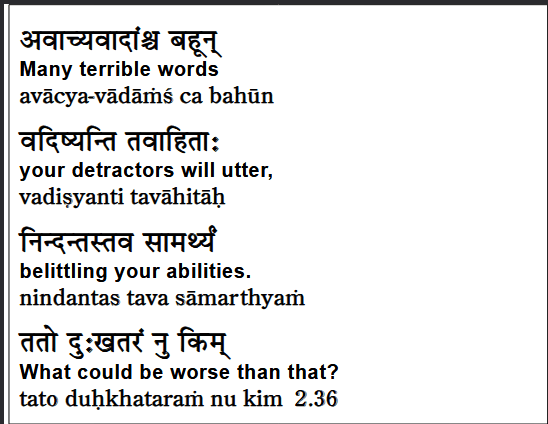

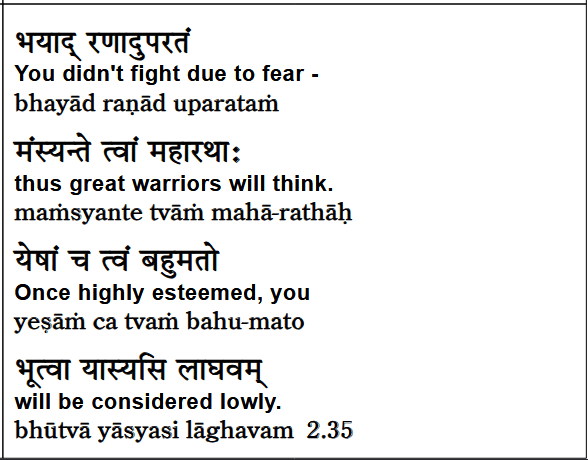

The commentator introduces this verse by making an argument. Suppose Arjuna feels that, “Okay, so a lot of people will criticize me.” Arjuna is thinking, “If I leave the battlefield, many people will criticize me. But those who know me, but my own family members—they will know that I left the battlefield out of compassion, and not out of fear.”

So consider: if Arjuna leaves the battlefield, what will it look like to most of the warriors? It’ll look like Arjuna left out of fear. And that’s the point that Sri Krishna is making here. He says—and the point is—everyone, even warriors on his own side—not only his enemies—will think he left out of fear, but even his own compatriots, the crowd of warriors will also think he left out of fear.

Sri Krishna says here in the second line:

Maharathaḥ, the great warriors—can mean generals, the leaders—but maharathaḥ, the great warriors, maṁsyante—will think, will consider tvām—you, Arjuna. All the great warriors out here on the battlefield, maṁsyante—will consider tvām—you, Arjuna—will consider you, in the end of the first line, uparatam—you withdrew, raṇāt—from the battle. You withdrew, you withdrew from the battle bhayāt—due to bhaya, due to fear.

Those warriors aren’t going to think that Arjuna left because of compassion. Remember, that’s what he felt in the first chapter when he looked across the battlefield for the first time, and he saw all of his beloved family members on the battlefield—on both sides—that would die in the battle. Arjuna was filled with pity and compassion. Not fear—not fear. We discussed that at some length.

But if he were to walk away from the battlefield—he’s in the chariot right now with Sri Krishna—if he gets out of the chariot and walks away, everyone is going to think he left the battlefield. Why? Arjuna uparatam—withdrew raṇāt—from the battle bhayāt—due to fear. Everyone will conclude.

Yeṣāṁ ca—in the third line—ca, and yeṣāṁ, amongst those, tvam—bahu-mataḥ bhūtvā—tvam, you, Arjuna, bhūtvā—having become bahu-mataḥ—highly regarded, highly esteemed. For you, Arjuna—you have become highly esteemed yeṣāṁ—amongst all these warriors, yāsyasi—you will go, laghavam. It’s an idiom. Laghavam means lightness. Literally: “you will go to lightness”—and you can’t take that literally. It’s a metaphor. You will be considered insignificant. You’ll be thought of as a lightweight—as someone who was cowardly. “Cowardly” is a nice way to translate that idiom. Yāsyasi laghavam—you will be taken lightly, you will be considered cowardly.

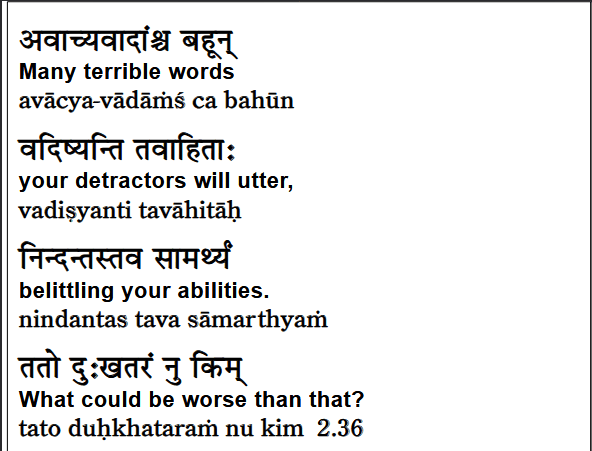

Okay then. Further, about the people watching Arjuna leave the battlefield—and what will they say?

Support the commentator. Imagine Arjuna’s state of mind—and suppose Arjuna is thinking that even if my own—Kaurava army considers me to be cowardly… Suppose Arjuna has just thought…

At least—the excuse—I’ve been actually mistakenly using “Kauravas” when I meant “Pandavas.” Arjuna’s compatriots are the Pandavas, and I think I misspoke once or twice before when I incorrectly used Kaurava to refer to Arjuna’s side. Arjuna, of course, belongs to the Pandava army.

So now suppose the Pandavas consider Arjuna to be cowardly for leaving the battle. But maybe Arjuna might think, “Well, at least the Kauravas”—his enemies—his enemies will be relieved. Why will his enemies be relieved? If Arjuna doesn’t fight, the enemies will be relieved because now they have a chance to win.

With Arjuna fighting, they have virtually no chance of winning. But if Arjuna leaves the battlefield, the Kauravas will be delighted, because now they have a chance to win. And here Shri Krishna says—no way.

He says in the second line: tava —your ahitāḥ, ahitāḥ is a word for enemy.your detractors okay but enemies is better your enemies vadishyanti will say will say what avachya vadant vadant words bhahun many words which are avacya words that shouldn’t be spoken words, that words that you can’t use in the mahabharata words that we can’t use in normal dialogue all those nasty dirty foul words that we can’t speak. He says even his his enemies the the count of us they may be relieved that Arjuna is not fighting but they’re not going to speak highly of Arjuna because they’re still going to consider him a coward yes they will be relieved that Arjuna is leaving the battlefield but his enemies will still consider Arjuna to be a coward and he tava samarthyam in the third line nindhanthaha not cursing uh bitterly belittling okay belittling putting down the common expression, putting down your samarthyam your capabilities, belittling your capabilities means seeing Arjuna this mighty warrior as a weak coward so seeing arjuna as a weak coward, even the enemies, enemies even though they’re relieved they will curse Arjuna with all these nasty words remember they’re mighty warriors mighty warriors are not going to accept weakness from another warrior like arjuna, so therefore they will curse him and belittle his greatness

Thaha dukhataram worse than that nu kim what what could be worse than that to be to be cursed by your enemies in this way

Now, but we have a few minutes before we conclude and there’s an important point we need to put it make here so here Sri Krishna is making the argument about what other people will say and there’s a problem here when our decisions are based on what others will think and say we may or may not make the right decisions based on what others think and what others say so let’s get the context very clearly, here Sri Krishna’s primary instruction to arjuna is do your duty, swakarma swa dharma is the word used here swadharma your own duties arjuna you must fulfill your duties that’s the primary argument then secondarily sri krishna goes on to say if you fulfill your your duties you’ll be praised and if you don’t fulfill your duties you will be cursed that’s really secondary right the primary argument here is do your duty that’s what you’re supposed to do and also you get to go to heaven by the way but remember the that’s the latter consequence is going to heaven but the initial consequence of doing the right thing so dharma is praise so if Arjuna fulfills his duties he’ll be praised if he fails to fulfill his duties he won’t be praised but now

Here’s the point I want to make suppose by following dharma so Arjuna is going to follow dharma and he’ll be praised for that suppose,

You’re you find yourself in a situation that if you follow dharma you’ll be criticized does that happen sure it happens there are plenty of times if you follow dharma you’ll be criticized I’ll give some common examples in India nowadays dowry is a is a big deal and people are waking up to the fact that this dowry system is highly abusive so suppose a family decides we’re not going to accept dowry we’re not going to request it we’re not going to to give it whatever it is by taking that position you’re following dharma but that may make you subject to criticism by other old-fashioned hindus and others so that’s an example by following dharma you may be criticized you should do it anyway follow dharma regardless of the criticism of others.

Maybe a better example, in fact commonly now in india in this country a family with with a marriageable son or daughter the son or daughter they will agree to have the son or daughter marry someone who is outside of their caste or even outside of their religion non-Hindu the son or daughter says says I very much love this person I want to marry this person please give me your permission even though this person is not in our cast or even though this person is not in our religion please give me permission and it’s difficult for parents I acknowledge that it can be very difficult for some parents to make this decision but the right decision is to say yes and to allow your son or daughter to marry the person they love but and and I would say without doubt that is following dharma but a good example by following dharma. These parents then become subject to the criticism of so many others because their son or daughter is marrying marrying someone that others consider unacceptable who cares if others consider the person unacceptable what matters is what’s acceptable to you and what’s ultimately acceptable is following dharma and here following dharma even if you’re criticized for it and this is different than Arjuna’s situation if arjuna follows dharma he’ll be praised for it but there are situations in life that by following dharma you are criticized and condemned for following dharma if you sacrifice your principles because of what other people will think and say that’s sad to give up your principles because of what other people will say but how strong it is how wonderful it is when you hold tight to your principles when you do what is right when you follow dharma regardless of other people’s opinions

just a side comment it’s not Arjuna’s situation but it’s relevant. Alright we will end here.

ॐ सर्वे भवन्तु सुखिनः

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti. Om Tat Sat. Thank you.