Gita Class 012, Ch. 2 Verses 23-28

Mar 27, 2021

YouTube Link: Bhagavad Gita Class by Swami Tadatmananda – Ch.2 Verses 23 – 28

Webcast every Saturday, 11 am EST. All recorded classes available here: • Bhagavad Gita – classes by Swami Tadatmananda

Swami Tadatmananda’s translation, audio download, and podcast available on his website here: https://arshabodha.org/teachings/bhag…

Swami Tadatmananda is a traditionally-trained teacher of Advaita Vedanta, meditation, and Sanskrit. For more information, please see: https://www.arshabodha.org/

Note about the verses: Swamiji typically starts a few verses before and discusses 10 verses at the beginning of the class. The screenshot of the verses takes that into consideration and also all the verses that were presented during the class, which may be after the verses discussed initially. We put the later of the two at the beginning

Note about the transcription:The transcription has been generated using AI and highlighted by volunteers. Swamiji has reviewed the quality of this content and has approved it and this is perfectly legal. The purpose is to have a closer reading of Swamiji.s teachings. Please follow along with youtube videos. We are doing this as our sadhana and nothing more.

———————————————————————–

ॐ सह नाववतु

oṁ saha nāv avatu

सह नौ भुनक्तु

saha nau bhunaktu

सह वीर्यं करवावहै

saha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै

tejasvināvadhītam astu mā vidviṣāvahai

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

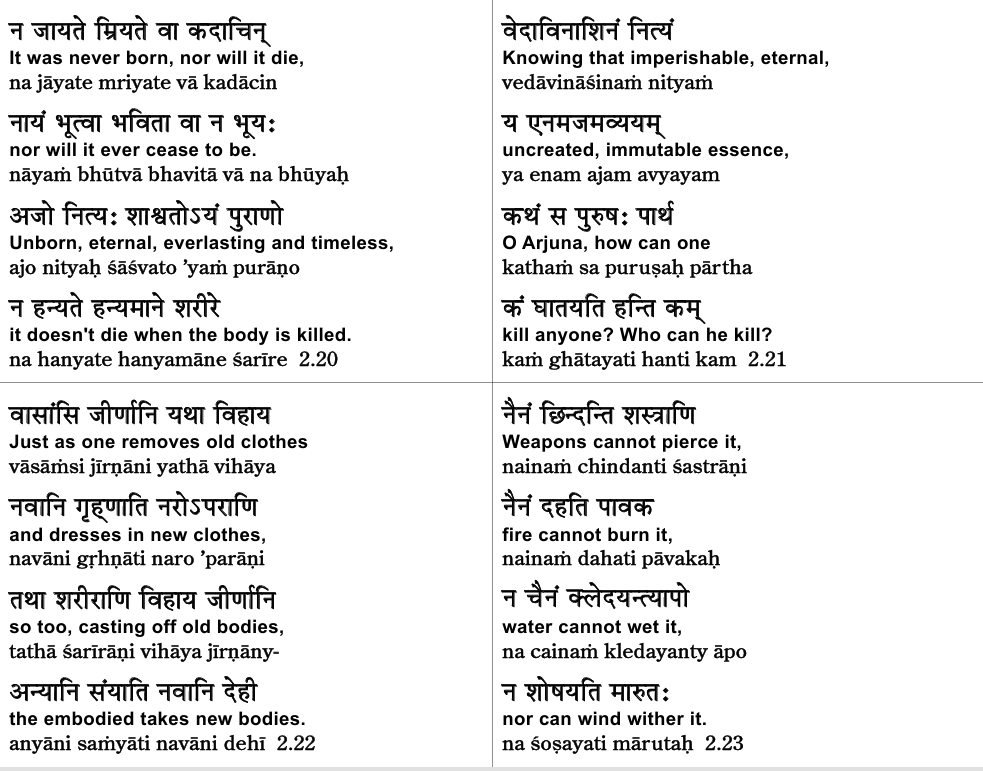

Welcome back to our Bhagavad Gita class. We continue to study chapter 2 and we’ll begin our recitation today with verse 20, the longer meter, and as always glance at the meaning as you’re listening to me so that you know what you’re chanting when you repeat after me.

Okay, let us return to where we left off. We have finished verse 22, so we begin today with verse 23. We are in this section. Chapter 2 is one of, I think, the second longest chapter or the longest chapter, and it includes several different subject matters. Most chapters include only one subject. Chapter 2 includes several.

So we saw the first part of chapter 2, which was still Arjuna giving reasons for why he shouldn’t fight the battle, and then finally seeking advice from Sri Krishna. Then it switched beginning with verse 11, where Sri Krishna began his spiritual teaching to Arjuna, which is the section we’re in right now. Later we’ll see some other topics will come, including Karma Yoga, which will come later in chapter 2.

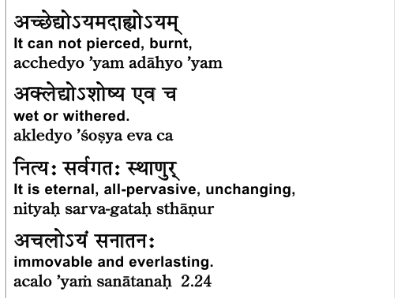

But here, Sri Krishna continues to encourage Arjuna to fight by helping Arjuna understand that Bhisma and Drona’s bodies will fall on the battlefield. Many bodies will fall on the battlefield, but nothing happens to Atma. Atma, the true self, Sat chit ananda, standard definition of Atma, Sat—an unborn, uncreated, unchanging reality that is chit—consciousness, that is ananda – full and complete. That Sat chiraananda atma is utterly unaffected by weapons, and that’s what’s being described here in verse 23.

Aenam—this, you get break up the words—na aenam chindantiyashtrani, shastrani—weapons, na chindantiy—cannot cut, cannot pierce. Aenam—this one, this Sat chit ananda atma. Weapons cannot cut it. Naitam dhati pavakaha—and pavakaha—fire, one of many words for fire—na dhati—cannot burn. Aenam—this one, Sat chit aananda atma.

Further, natcha, cha, and at the end of the third line, apaha—water, water, na kledayantiy—water, it’s always plural. Water, na kledayantiy—cannot wet or dampen. Aenam—you have to separate—and aenam, aenam—this one, this Sat chit ananda atma.

And finally, na sho shayati maruta ha—maruta, wind, na sho shayati—cannot dry it out, cannot make it withered.

You might have noticed that we have four of the five fundamental elements here. Beginning with earth—shastra, weapons, are made of the element earth. So first you’ll see element earth cannot affect atma, then comes pavakaha—fire, agni—agni cannot affect the element, cannot affect atma. Then comes the element apaha—water—cannot affect atma, and finally maruta—wind, vayu, more commonly called—vayu cannot affect atma.

So four of the five elements, you might say, what about the fifth element, akasha? Akasha can’t affect anything—no necessity to mention akasha here.

But what is the point here is that atma is a different kind of reality. This is one thing that advaita vaydanta is famous for, especially Shankara’s teachings, advaita vaydanta, showing that atma doesn’t share the same level of reality as the material universe.

Little bit like in the language I think we’ve used in this class before is—atma is more real than the world. Remember our definition of real is—that which doesn’t get born, that which doesn’t die, that which doesn’t change, that which always exists.

So that atma—being unborn, unchanging, and eternal—is more real than the world. The world that comes and goes, the world is constantly changing. The world was born some 14 billion years ago, the world will eventually cease to exist. Atma is more real than the world, and anything that’s more real can’t be affected by what is less real.

When you’re sitting in a movie theater and you’re watching some movie where a bomb explodes, that bomb in the movie can’t affect you sitting in the theater. You’re more real than the theater.

Or in a dream if you’re being chased by an elephant, the elephant in the dream can’t hurt you because you are more real than that elephant.

So atma, being more real than the world of elements, cannot be affected or hurt in any way by anything in the world.

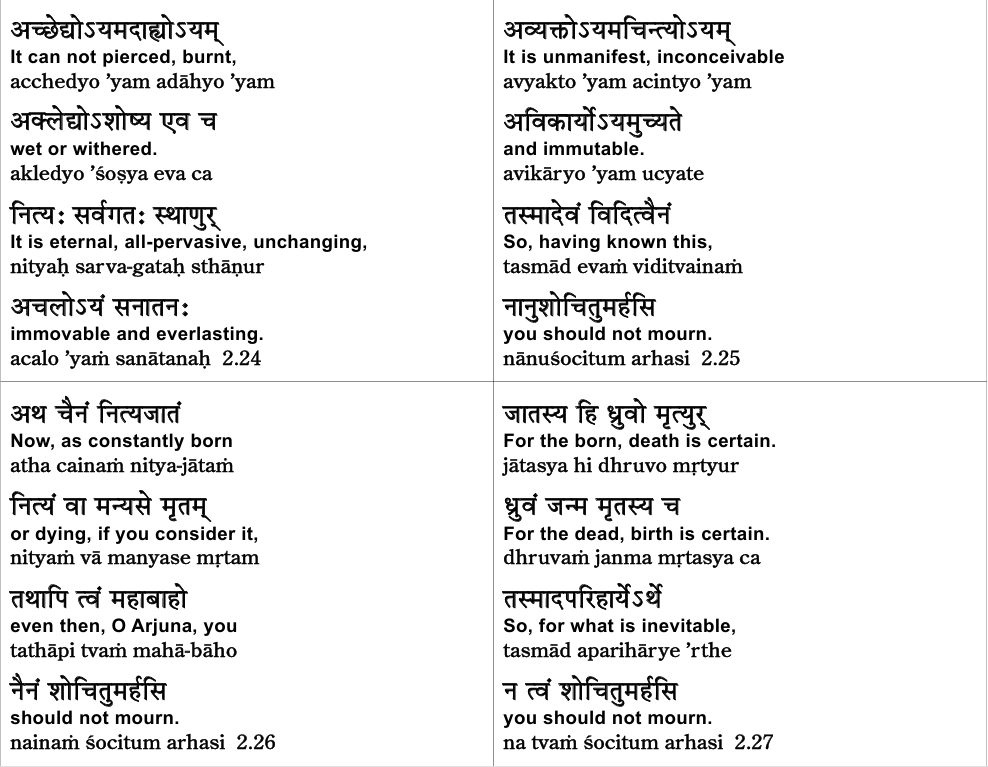

You continue—same idea, sorry. First half basically rephrases what was taught in the prior verse.

So chaed yaha ayam—prior verse we had the pronoun anam for atma. Here we have the pronoun ayam for atma. This one, this atma is achaedyaha—it can’t be pierced, it can’t be cut by any shastra, by any weapon. Ayam—this atma is a dachh yaha—it can’t be burnt by fire. If this atma is a chaed yaha—it can’t be made wet by water and a shoshha eva cha—it cannot be dried, a shoshha—it cannot be dried out by the winds.

So restating what was said in the prior verse. Now there’s an important question we can ask here—why, based on what, can Arjuna claim that atma is unaffected by these four elements? And he gives the reason—Sri Krishna gives reason in the second half of the subverse.

Atma is nithya. And I give the words first and then make some observation. Simply the words are—atma is nithya—eternal. Eternal meaning unborn and unchanging. Atma is sarva ghataha—literally all-pervasive. There is one all-pervasive consciousness manifest in all sentient beings, as we’ve discussed before.

Atma is tanuhu—stable, unchanging. Literally, stanu is a post. But it means that which is stable, and in this context, that which doesn’t undergo any kind of change.

Atma is achalaha—unmoving, also means unchanging. Ayam—this atma is sanatana—eternal, everlasting, timeless, beyond time, more real than time. Anything that exists in this world ages with time. But that which is more real than this world of time is not subject to change, including aging.

Now something very important to point out here. And that is this statement—atma’s eternal, all-pervasive, unchanging, everlasting. That sounds like so many scriptures. Even like Hebrew scriptures of the Old Testament or Greek scriptures of the New Testament of the Bible. Or Arabic scriptures of the Quran. These kinds of statements we hear, they sound very scriptural. Atma is eternal, all-pervasive, unchanging. And that scriptural sound leads us to think that, oh, this is a matter of belief. I have to believe this. Atma is nitya. I have to believe atma is nitya, atma sarva ghataha. I have to believe that atma is all-pervasive.

And we make that connection because we’re so accustomed to hearing scriptural statements that dictate what you should and should not believe. There are a great number of scriptures, including portions of the Vedas. The whole, the prior part of the Vedas, that deals with rituals and many other topics. That portion of the Vedas does indeed deal with lots of matters of faith.

But we’re not studying that portion of the Vedas. You might have learned that the Vedas have two broad parts. There’s a karma kanda and a gyanakanda. The karma kanda is the part that deals with all the rituals and matters of belief. But the gyanakanda is the portion that deals with knowledge—specifically, does not deal with matters of faith. It deals with matters of knowledge.

That’s what determines gyanakanda, the portion of the Vedas that deals with matters of knowledge. That portion of the Vedas, as you might know, is compiled at the end of each of the four Vedas. So each of the four Vedas has a gyanakanda that occurs at the end of the Vedas. Therefore, they’re called Vedanta. Anta means end. The antabhaga, the final portion of the Vedas, is Vedanta. And that’s what Sri Krishna’s teachings are based on.

The point I’m making is even though this is all scriptural, no doubt. But even though the great majority of scriptures do indeed deal with matters of faith and belief, the gyanakanda of the Vedas, the Vedantic teachings that come into Vedas, and the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita, which is based on those Vedanta…

And just to make a connection for you, the name of that section, gyanakanda, the technical name is Upanishad. And in a prior class, we quoted several verses from the Katha Upanishad. Sri Krishna was quoting and paraphrasing verses from the Katha Upanishad, part of the gyanakanda.

So the point I’m making here is even though most scriptures deal with matters of belief, this particular scriptural passage does not deal with matters of belief. Atma is not something you believe in. Yeah, just sounds so funny to me. Do you believe you exist? Atma is your true nature. You know you exist. It’s not something you believe in. It’s something you know in a very simple intuitive way.

But then, you know that you exist as a conscious being. That much is already known to you, but the true nature of that consciousness is unknown to you. Look at this. Partially known. Atma is partially known. You know that atma is—you know that you are a conscious being. Conscious, chit, being, sat. You know that you are such a chit. You may not know that you’re ananda. And that’s what all these words are helping you to understand—the true nature of satchidananda.

So when Sri Krishna says here, atma is nityaha, eternal, he doesn’t mean that you should believe that atma’s nityaha. It means you should discover your own true nature to be unborn and uncreated.

How do you make that discovery? Well, in part with the help of these teachings, but also in terms of your own experience. You have to find out how what is born and changing is your body and mind. Your body is born and constantly changing. Your mind was born and is constantly changing. And that changing body and mind are present in your experience, as is consciousness. But in your experience, body and mind change; consciousness doesn’t change.

Consciousness is the unchanging light of awareness by which you know the changing conditions of your body and mind. I’ll say that again: consciousness is the unchanging light of awareness by which you know the changing conditions of your body and mind.

I’m just giving you one example. We’re not going to—we could spend hours going through with each one of these words. We’re not going to do that here. But the point is each of these words are meant to help you discover your true nature. They’re not meant for belief. You’re not supposed to believe that atma is all-pervasive, sarvagata. You have to discover how it is so—that your consciousness is not stuck inside your head. You have to discover that.

Again, with the help of the three things: Shruti, Yukti, and Anubhava. We discover with the help of Shruti—scripture, Yukti—reasoning, and Anubhava—experience. All Vedanta is based on these three. Shruti—scripture, Yukti—reasoning, Anubhava—experience.

So Sri Krishna says atma is sarvagata—you have to discover how atma is, your consciousness is all-pervasive using Shruti—scripture, using Yukti—reasoning, and using Anubhava—experience.

Atma is sthanu—unchanging, achalaha—unchanging, sanatana—eternal. You have to discover this using Shruti, Yukti, Anubhava. This is absolutely not meant for belief.

And a final point here, and that is—from a Vedanta standpoint, belief is fundamentally weak. And when I say fundamentally weak, what I mean is that belief can be shaken. Belief is not absolutely reliable. You all know of someone, a very pious person who used to pray every single day until some tragedy happened. And that tragedy was so horrible that their faith was shaken and they stopped praying. How terrible that is when that happens. It’s very sad. But what that means is there is no such thing as unshakable faith or belief. Any kind of faith or belief is subject to being shaken if the circumstances are right.

On the other hand, knowledge is unshakable. Your knowledge that 2 plus 2 is 4—could that knowledge be shaken in the midst of a terrible tragedy? If you are in the midst of some horrible situation, really upset, in a state of chaos—in the midst of that horrible situation, would you have any doubt that 2 plus 2 is 4? Knowledge can’t be shaken.

So let’s be very clear. Our goal here is not belief. Our goal here is knowledge. Belief is important—early on in chapter 4 we’re going to see a famous verse where Sri Krishna says, Shraddhavan labhate jnanam—one who has faith gains knowledge, meaning faith leads to knowledge. Faith or belief is not the goal. Knowledge is the goal.

Okay, enough said. Continuing.

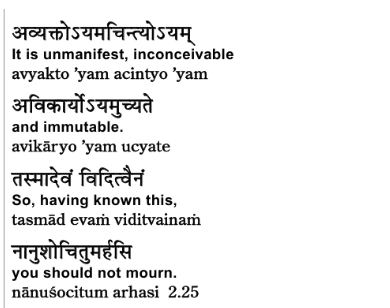

Hase na nu sho chitam har hase

You see the pronoun ayam in the first line. The ah drops off due to grammar rules. Ayam comes twice. Ayam—this one, this atma—is avyaktaha. Vyaktaha means manifest, visible. Atma is avyaktaha. It is not visibly present in the world because it’s not a physical thing. We said before, atma is more real than the world of elements.

Also, atma, ayam—this one, last word in the first line, ayam, this atma—is achintyaha. Now, achintyaha literally means unthinkable, but that’s not a very helpful translation. The commentator suggests that it is better to understand the word as un-inferable—not unthinkable, but un-inferable.

And that uses a little bit of a technical part of logic, where when we use inference— inference says you see smoke rising above the mountain, and you infer the presence of fire. You don’t see the fire, but you see the smoke, and based on the presence of smoke, you infer the presence of fire.

But in order to infer the presence of fire, you have to see the smoke. So something has to be visible to you in order to infer the fire. The fire can’t be seen. If the smoke couldn’t be seen, also you couldn’t infer the fire. So smoke has to be visible. Something has to be visible to make an inference. Something has to be perceptible to make an inference.

If you drink water and it’s sweet, you can infer that somebody put sugar in the water. If you drink water and it’s salty, you can infer that there’s salt in the water. So the point I’m making is: inference depends on a perception.

When Sri Krishna says here that atma is achintyaha, the commentator Madhusudana Saraswati says atma cannot be inferred. And atma cannot be inferred—why? Because in order to make an inference, you have to perceive something first. You have to perceive the smoke to infer the fire. You have to taste the sweetness to infer the presence of sugar, etc. So since atma is not perceptible, therefore atma cannot be inferred.

Finally, ayam atma—in the middle of the second line, ayam, this one, atma, ucchyate—is said. Is said to be what? Avikāriyaha. We’ve been talking about this—unchanging, immutable. Anything that changes is subject to decay and destruction. Atma is unchangeable, therefore not subject to decay and destruction.

Tasmāt—now here comes a big conclusion. So Sri Krishna began talking about atma with the eleventh verse of chapter two when he began teaching. And he said there, that Arjuna, you shouldn’t grieve. You grieve for those who don’t deserve grief. And now you conclude here:

Tasmāt, therefore Arjuna, ayam viditvā, enam viditvā—having understood enam, you have to break those words apart—viditvā enam—having understood enam, this one, this atma, having understood it evam, thus, having understood atma in this way:

Na anu-shochitam arhasi, na arhasi—you should not shochitam—grieve. You have no reason to grieve. This is not a matter for grief or mourning.

Notice he says, therefore Arjuna, having viditvā, having known atma thus. He doesn’t say believing thus. He doesn’t use the word belief here. He uses one of the most common words for “to know.” It comes from the root vid—vid, to know. The word veda, name of our scriptures, comes from the root vid, to know. So it’s the most common word for “to know.” He uses that here—viditvā—having known, having understood. He doesn’t say having believed or having faith in atma. As we said, this is not a matter of faith at all.

So as we turn to the next verse—and let’s see the verse and I’ll explain the shift:

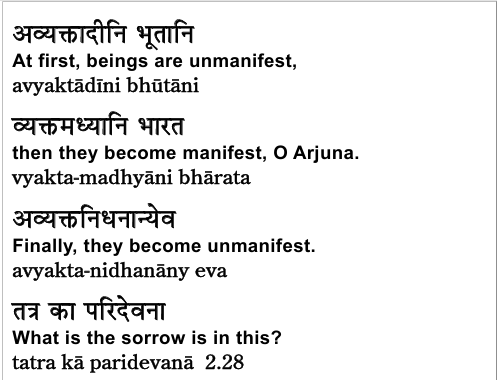

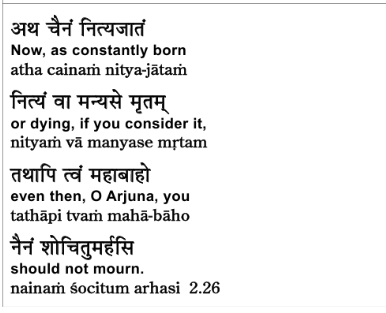

Ataḥ—now, and that’s a good word for making this transition—now. Ataḥ ca—and now. Look at the second line: manyase. If you think. Manyase—if you think. If you think—back up—ca enam, enam, this one, this atma—if you think this atma is nityajātam, jāta—born, nityajāta—eternally born.

Let me give you the meaning of the words first. So suppose, manyase—suppose, Arjuna, you think, you consider that enam—that this atma is nityajātam, is eternally born. Nityam vā mṛtam vā—or nityam mṛtam, eternally dying.

If you consider atma to be eternally born or eternally dying—now, there are several ways of interpreting that. I think the most helpful way of interpreting this is to connect it to the sūkṣma śarīra.

So far, our discussion has been about atma. So the basic principle that Sri Krishna has taught is that you need not grieve because nothing happens to atma. So the whole prior discussion has been focused on satchidānanda ātma.

Now let’s consider from the standpoint of sūkṣma śarīra—the subtle body. Remember in our metaphor—our computer metaphor—you have hardware, like your computer has hardware, you have hardware—it’s your physical body. And just as your computer has software, you too have software. Software is all your mental faculties. Your software includes your mental faculties, your faculties of sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch; your faculties of grasping, walking, and talking. The prāṇa that enlivens your body—all of these constitute your software, so to speak.

The basic difference is that hardware is physical, tangible. Software is not physical, tangible. As we said several times, your computer’s hard drive weighs several ounces. The software on a hard drive weighs nothing at all. We’ve seen that metaphor before.

So the software that enlivens you—the sūkṣma śarīra, which is non-physical, non-tangible. Non-physical just means subtle—means non-tangible, means you can’t see, hear, taste, smell, or touch it. Doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Does software exist? Sure. But have you ever seen a bit? Software is bits. A bit is not something you see. Bit is an idea. Software is all conceptual—it’s ideas. It’s not a physical reality. Okay, enough said.

So now we’re going to shift with this 26th verse. We shift our perspective from atma to sūkṣma śarīra. Previously, Sri Krishna says, nothing happens to atma, therefore you need not grieve. Now, Sri Krishna is going to say, nothing happens to sūkṣma śarīra either. Therefore, you need not grieve.

And he says here, suppose—ātmanam manyase, O Arjuna—if you think that enam, this atma, is nityajātam—eternally born, means born again and again and again, born into one body after another body, born into one life after another life—nityam vā mṛtam in the second line. Or if you think that atma is eternally dying—I’m sorry, that sūkṣma śarīra is eternally dying.

So with regard to sūkṣma śarīra—getting born again and again and again, and then dying again and again and again. So from the standpoint of subtle body, which goes from one life to the next—the philosophers like calling it transmigrating entity. Fine.

So even from that standpoint, tathāpi in the third line—even then—mahābāho, O mighty-armed Arjuna—even then—tvam, you—na śocitum arhasi, you need not grieve—enam, for this one.

Here enam, this one, is referring not to atma but to the subtle body. Why? Why should Arjuna not grieve for the subtle body?

Well, again, the physical body dies on a battlefield. The subtle body, at the time of death, as we’ve discussed before, the subtle body detaches itself from the physical body, is driven on by the laws of karma to acquire another physical body for the sake of discharging the accumulated karmas. This is all according to the laws of karma.

So here, Sri Krishna changes his perspective and gives Arjuna a whole different reason, a whole different basis, for not grieving for his loved ones—his Bhisma and Drona.

When you love someone, is that love for their physical body? That doesn’t make sense. The love is for the person, the personality. Well, that personality belongs to the sukshma sharira, does it not? Not to the physical body. That’s personality that we love—a person’s kindness, a person’s intelligence, a person’s wisdom, a person’s love. All of these features belong to the sukshma sharira. That’s what we love about a person.

And that doesn’t die when the bodies are struck down on a battlefield. That’s the point. So the bodies die; the subtle body travels on.

And the commentator—here’s Madhusudana Saraswati—draws our attention to the law of karma, which guarantees that the subtle body doesn’t die when the physical body dies.

Let’s just see this briefly. I mentioned before that this doctrine of karma is very complex, very elaborate. And I have produced a series of three or four videos on this topic. You can find those videos on my YouTube channel—look up “Doctrine of Karma”—and those videos will tell you in great detail all that you need to understand.

But let’s just see one point here in particular that’s described in those videos. But here, the commentator wants to make—the commentator makes—a very strong point. And here’s the point:

When, at the time of death, the physical body dies and it is burnt—it is reduced to ashes. So the question then is: well, if the physical body is reduced to ashes after death, then why isn’t the subtle body also in some way reduced to ashes? The physical body gets destroyed after death—why doesn’t the subtle body get destroyed at the time of death?

There’s some logic to that, according to the doctrine of karma. And here’s the logic: every action must yield its result. This is the basis of the doctrine of karma. Karma means if you do an action, you have to get a result. If I drop the pen, it has to fall. For an action (karma), there has to be a result (phala).

And here’s where the doctrine of karma goes further, by saying that in this life, you have committed many karmas for which you have not yet received the results. To commit a karma and not yet receive a result is like dropping this pen and the pen doesn’t fall. Suppose the pen remained suspended in space. The action was committed, the result is pending.

When you’ve committed many actions in this lifetime, not all of those actions have yielded their results. Many of those actions give results which are pending. And those pending results eventually have to take place. The pen eventually has to fall. The results of the deeds you have committed eventually have to fructify.

But suppose you die before those results fructify? Well, the law of karma is such that you can’t have results that don’t fructify. Those results must fructify. And they must fructify to whom? Whoever committed the action must receive the result. Whoever committed the action must receive the result.

And the one who committed the action is associated with the subtle body. Your physical body doesn’t commit any action. Your physical body is an instrument. It’s an instrument you use—like when you use a spoon to eat ice cream. You use a spoon to eat ice cream. Who gets the calories? Not the spoon. The spoon is just an instrument.

So the point here then is that your body is just an instrument. So your body is not the agent of action, nor is consciousness (atma) the agent of action. Body is just an instrument. Consciousness is unchanging. Unchanging consciousness doesn’t do anything.

Your decisions to do things—those decisions take place in your mind, intellect. And your mind and intellect are part of your subtle body. So the point here is that the one who commits actions is associated with your subtle body.

To finish this up, we said: when you die, many actions you’ve committed leave pending results. Those pending results must fructify. And the one who committed those actions must receive those results. The one who committed the actions is associated with the subtle body.

And here, the doctrine of karma ensures that that subtle body—for the sake of fructifying those pending results—the integrity of the subtle body is maintained at death. The integrity of the physical body is not maintained. It returns to elements. But the integrity of the subtle body is maintained by the law of karma.

I call it karmic glue. Karmic glue holds the subtle body together, drives it on to acquire another physical body for the sake of receiving those pending results.

Now, the commentator here makes a point, and that is: according to the doctrine of karma, it is guaranteed that the subtle body will survive death, travel on, and take another birth. Why? Because according to the doctrine of karma, those pending results must fructify.

This is the doctrine of karma in its most simple form: for every action, there has to be a result. But then things get more complicated when you commit an action and then you die—very inconveniently—leaving the results pending. And that’s why the subtle body maintains the integrity of the subtle body, drives it on to receive the results of those pending karmas.

It’s a little bit like in science—there’s a law of conservation of energy, conservation of mass, conservation of momentum. This is similar. It’s conservation of karma phala. The results are conserved, which is to say that once you’ve committed the action, even if you die, the result is conserved, so to speak.

Now, I’ve completely distracted myself here—we are… So, that’s it.

So, Sri Krishna says, from the standpoint—just to summarize—verse 26, from the standpoint of sukshma sharira also—prior verses are from the standpoint of atma, but in verse 26, Sri Krishna shifts to the perspective of the subtle body. From the perspective of the subtle body also, Arjuna, you need not grieve.

And he continues:

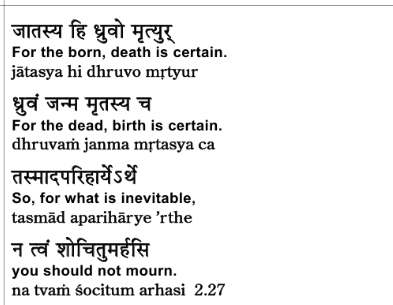

Very simple logic here. Dhruvaḥ—the word dhruvaḥ… many of you know Dhruva as the pole star, but dhruvaḥ literally means stable, unmoving. So the pole star is called Dhruva, or Dhruvaḥ, because it’s the only star that doesn’t move. But dhruvaḥ as “pole star” is a secondary meaning. Primary meaning is that which is unmoving. That which is—and here in this case—it means that which is certain.

Dhruvaḥ—it is certain. What is certain? Jātasya mṛtyuḥ—mṛtyuḥ, death, is dhruvaḥ, certain. Jātasya—for anyone born. For anyone born, death is certain. Dhruvaṁ ca—and it is, in the second line, dhruvaṁ ca, and it is also certain—what is certain? Janma—birth, mṛtasya—for anyone who has died.

So, to paraphrase the first two lines: death is certain for anyone born, and birth is certain for anyone who dies. According to the doctrine of karma, the sukshma sharira, its integrity is maintained. It is driven on by the laws of karma—the winds of karma, we’ll call them—drives that sukshma sharira on.

And this reasoning—sometimes we overlook the obvious. Sometimes, sadly, at a time of loss, when you lose a loved one, sometimes even mature adults will ask, “Why did he or she have to die?”

Well, they got born.

I don’t mean to make light of it. But they died because they were born. And really speaking, there’s only one way to avoid dying—and that is not to be born in the first place. But no one would choose not to be born in the first place. Therefore, death is inevitable.

In American English, they call it a “package deal.” When you get born, it means death comes along with it.

Tasmāt—therefore, Arjuna, aparihārye arthe—you have to put the a back in—arthe, with regard to this matter which is aparihārye, unavoidable. With regard to this unavoidable matter of death, na tvaṁ śocitum arhasi. Na arhasi—you should not. Tvaṁ, you. You should not śocitum—you should not grieve. There is no need for you to grieve.

There’s something so basic here that we lose sight of it: the inevitability of death. We all get it logically. But we don’t get it emotionally, right? We all know death is inevitable. But when death comes, we can’t deal with it emotionally.

It’s a little bit like children. When you tell a child who has had three cookies, and the child says, “Mom, can I have another cookie?” Mom says no. Three cookies is enough. Mom says no. The child starts crying. Why? Because the child can’t have it his way or her way.

The child wants the world to behave in a way that’s suitable for the child. But the fact is, Mom is not going to give four cookies. Mom is going to stop after three cookies. The child has to learn to handle that.

The child has to learn that the world does not conform to our expectations, to our wants, to our desires. And that applies to the adult reality of dealing with death. It’s an emotional issue. We understand death intellectually. Emotionally, we have to grow up, in a manner of speaking.

The child has to grow up so when Mom says no, the child doesn’t cry. In the same way, we all have to grow up—in a manner of speaking—so that we can deal with death emotionally with more grace, with more acceptance and understanding.

Okay, yeah—we have time.

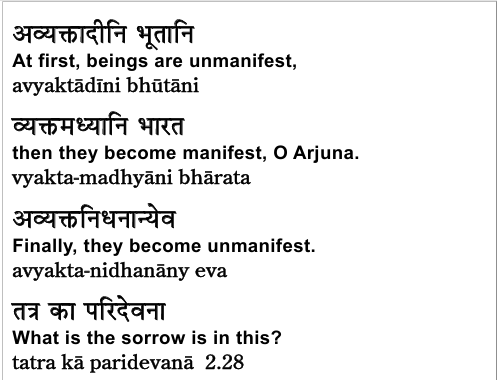

Bhūtāni—beings, living beings. Living beings means sthūla sharīra—physical body—enlivened by a sukshma sharīra, subtle body. A sthūla sharīra without a sukshma sharīra is a corpse. And a sukshma sharīra without a sthūla sharīra is unmanifest—not a living being.

So bhūtāni here—beings. Beings means a combination of subtle body and a physical body. Just like your sthūla sharīra, physical body, invested with a sukshma sharīra, subtle body.

These are avyakta-ādīni—these beings are avyakta ādi—ādi at the beginning. They are avyakta. Vyakta means manifest. Avyakta means unmanifest.

And here we’re referring again to the travel of the subtle body. Before a subtle body invests itself in a new physical body, it is avyakta ādi—it is unmanifest in the beginning, before the subtle body is connected to the physical body.

Vyakta madhyāni—and madhyāni, in the middle, those beings are vyakta—manifest. After the subtle body is invested into the physical body, then it is vyakta—manifest.

So from the moment of conception, in the Hindu worldview—from the moment of conception—the sukshma sharīra is associated with the physical body, and therefore it is vyakta—manifest.

First it is vyakta—manifest—as an embryo inside the mother. Eventually it is born, and it lives its whole life being vyakta—manifest.

Finally, avyakta nidhanāni—eva nidhanāni bhūtāni—bhūtāni, all those beings, nidhanāni at the end, meaning after they die—all those beings are avyakta.

Avyakta nidhanāni—those who in the end become unmanifest again. After the body dies, and after the sukshma sharīra detaches itself from the body, it travels on—once again unmanifest.

End of the second line—Bhārata is an address, a term of address. O descendant of Bharata, O great Arjuna—this is true for every single person.

Before they are born: avyakta—unmanifest.

After they are born: vyakta—manifest.

After they die: avyakta—unmanifest.

Tatra—with regard to this matter—kaḥ pari-devanā? What’s the problem?

In American English: What’s the problem?

You know: bāt kyā hai?

So there’s no problem. This is the cycle of life.

The Hindu worldview is of everything being cyclic. The universe itself is cyclic—going through periods of manifestation and dissolution—sṛṣṭi and pralaya. The universe goes through periods of manifestation and dissolution.

Similarly, every sukshma sharīra goes through periods of being associated with the physical body—manifest—and not being associated with the physical body—unmanifest.

So these cycles of being vyakta—manifest—and avyakta—unmanifest… this cycle is natural. This cycle is inevitable.

Therefore, Arjuna, tatra kaḥ pari-devanā—where is the problem? There’s no problem.

We’ll continue next time.

सर्वे सन्तु निरामयाः ।

सर्वे भद्राणि पश्यन्तु

मा कश्चिद्दुःखभाग्भवेत् ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niraamayaah |

Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu

Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet |

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, May All be Happy,

2: May All be Free from Illness.

3: May All See what is Auspicious,

4: May no one Suffer.

5: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti. Om Tat Sat